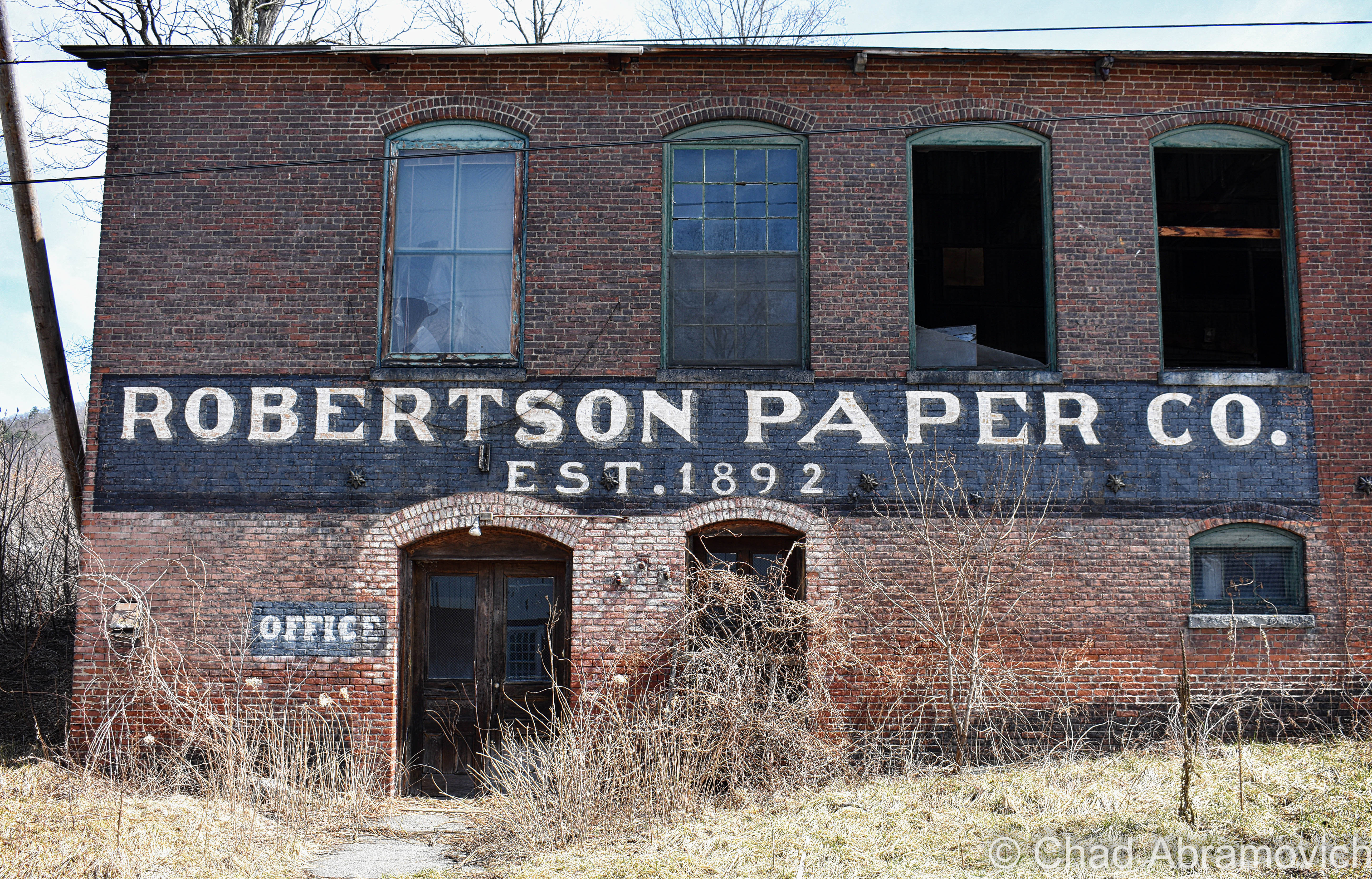

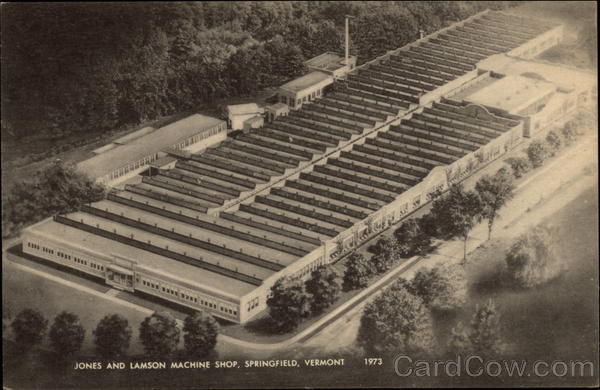

It’s kind of a rarity to find abandoned industrial lots in Vermont nowadays, so when I was made hip to the existence of this old factory in Springfield, I bumped it up to the top of my to-explore list. And I’m glad I did – it’s since been demolished.

On the banks of the town’s engine; the Black River, existed the ruins of a far-reaching factory – in both its size and its metaphor.

The origin of this building goes back to 1907 and the genesis of Springfield’s metamorphosis into a hub of innovation and industry – a culture that would become inexorable to the extraordinary marvels that enhanced Springfield’s legacy and is still an enduring source of discourse even after the bustle went bust.

Seriously, it’s rumored that Springfield, Vermont was such an adversary, that Hitler allegedly put it on his number two spot to bomb into oblivion had his Nazi party of terrorists ever atrocitied their way over here to America.

That all changed after the second world war’s hunger for humans ended. Job-seeking soldiers started coming back home, while machine tool contracts stopped coming in – and the town’s prosperity stalled, before succumbing to a steady multi-decade death rattle, leaving Springfield’s postmortem giving off incredulous vibes that anything I’ve talked about in the above paragraphs ever happened here.

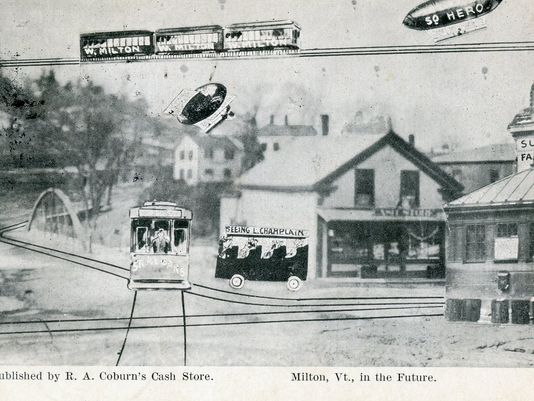

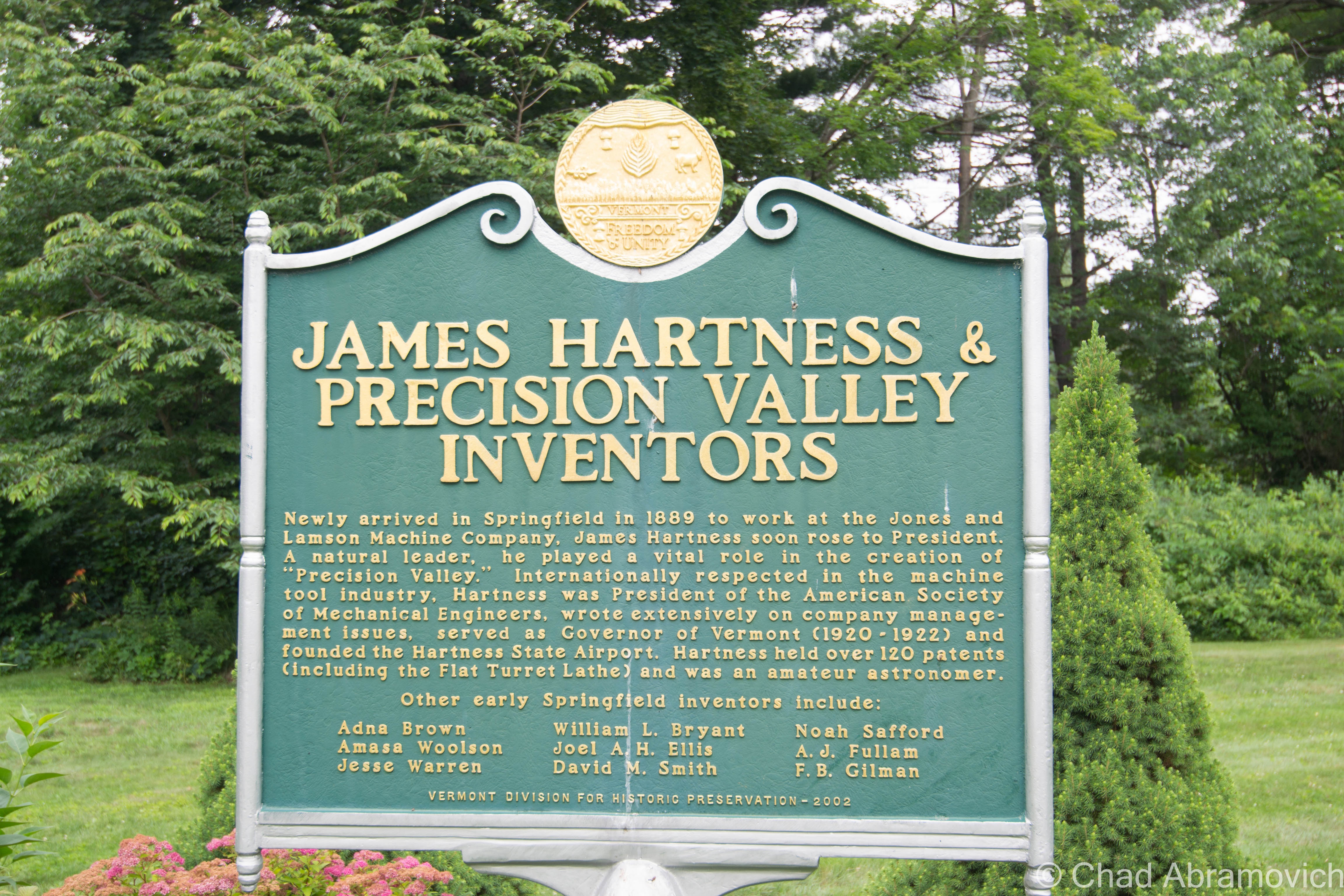

But, a lot of stuff used to be invented and then made here – until as recently as a few decades ago. So much so, that for about a good century – from the 1890s to the end of the 1980s – the region became to be known as “Precision Valley” – due to it practically inventing the precision tool industry, and had the highest per-capita income in all of Vermont. Even today, some locals still call their part of the state Precision Valley – which approximately is considered to be anchored from Springfield to Windsor (Windsor is another very cool little Vermont town worth a road trip). The most significant component of all this was the machine tool industry, and the decrepit factory that I’m gonna be blogging about was once the heavyweight of the genre.

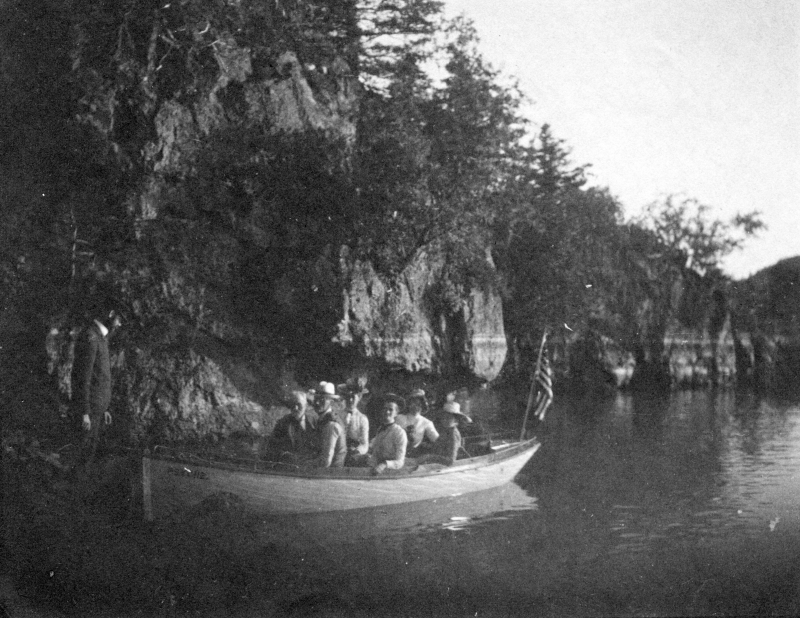

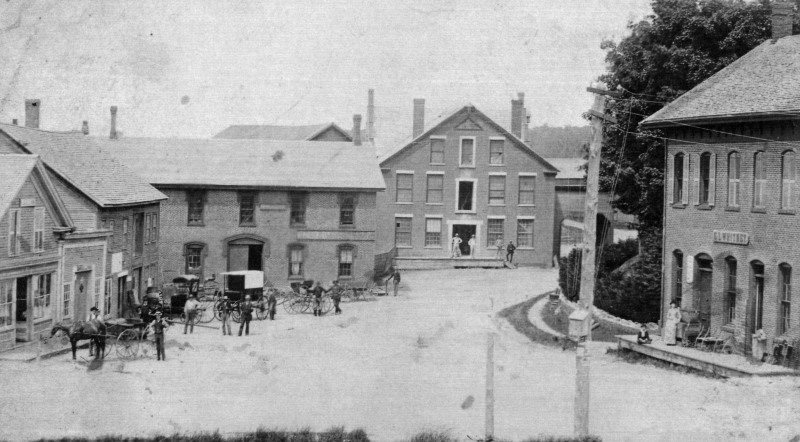

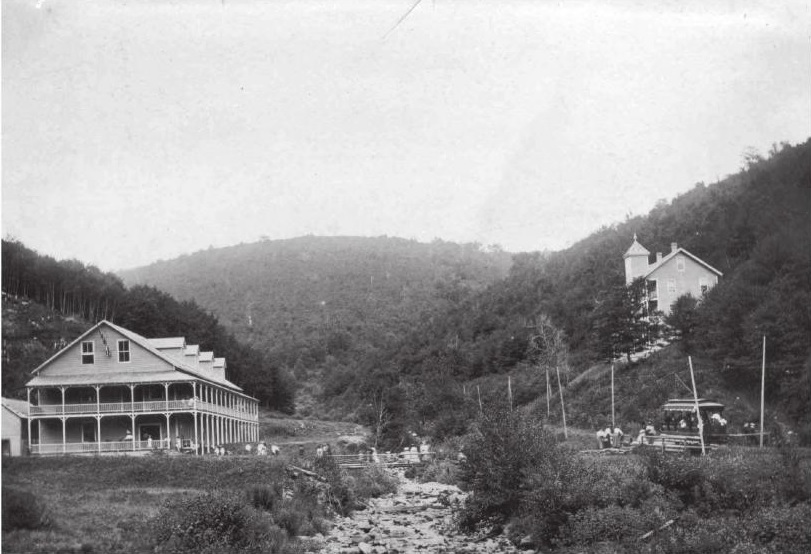

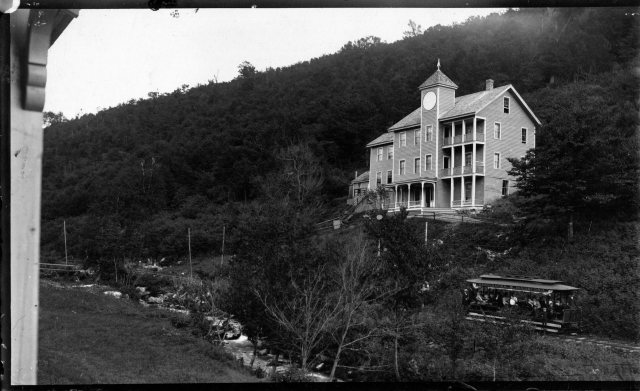

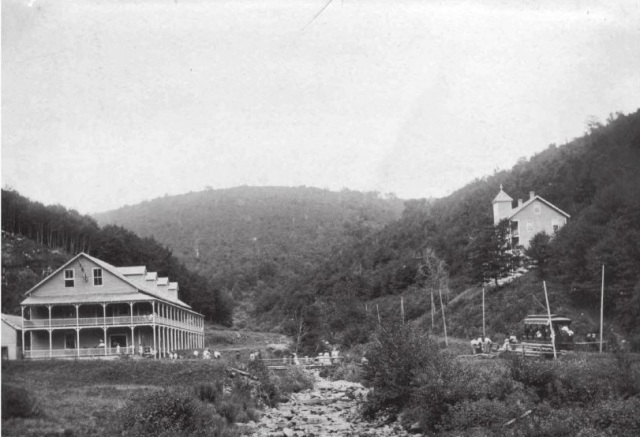

In 1869, the Black River rivered too much and flooded and wrecked Springfield village, and as the town struggled to rebuild in the subsequent years, a big fire in 1880 basically undid all the progress and doubled down on the destruction. So a few Springfieldians schemed up a hook to lure people and investment.

Adna Brown, the general manager of Parks and Woolson – a manufacturer of woolen cloth finishing machinery that was both the first existing manufacturing complex and the last major mill to operate in Springfield – heard that the struggling Jones and Lamson machine tool factory up in Windsor was for sale, and was struck by cleverness. Jones and Lamson had been in business since 1829 and had made a smorgasbord of goods, from rotary pumps, rifles, machines to drill gun barrels, stone channelers, engine lathes, and sewing machines. Their old building is the present-day American Precision Museum, one of Vermont’s coolest archives that showcases many of the things invented in Precision Valley!

Brown put together a group of intrigued investors, and in 1884, persuaded the invoked of a new Springfield law that exempted any industry that would move to town from taxation for 10 years. It worked.

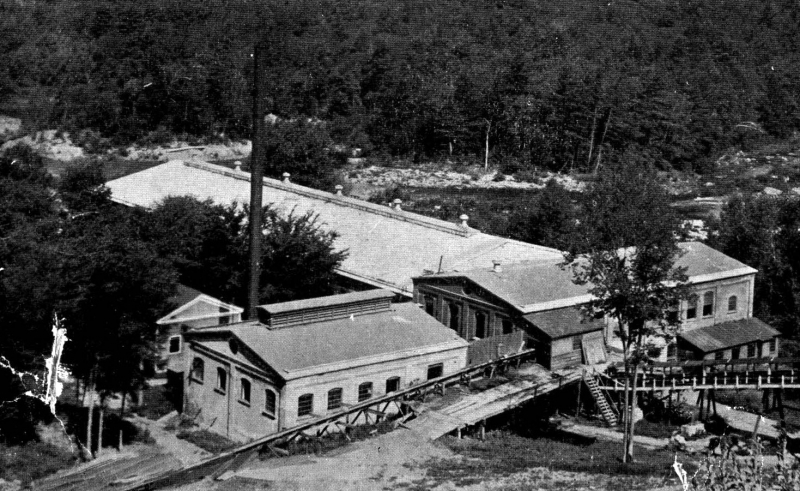

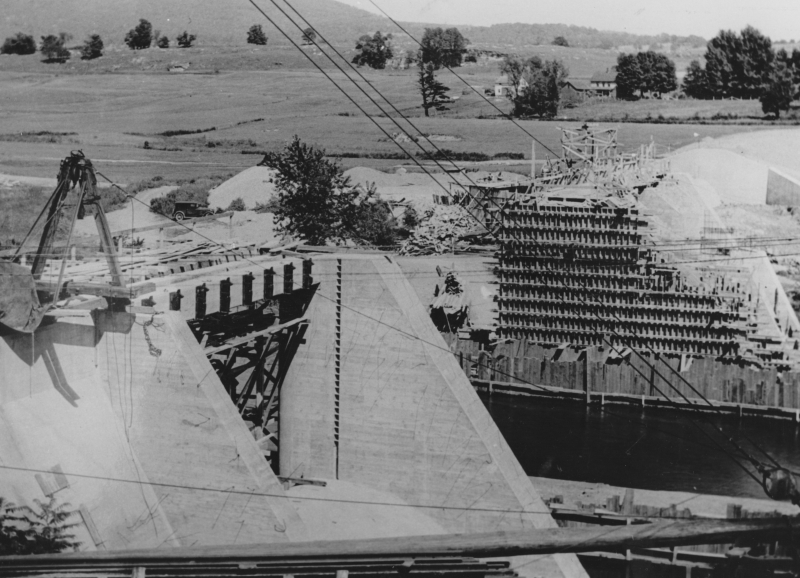

Brown bought Jones and Lamson and moved it to Springfield in 1888. Construction started on the new J&L digs in 1907 on the banks of the Black River, and Brown’s good business sense kenned he’d need the right person to run the new enterprise.

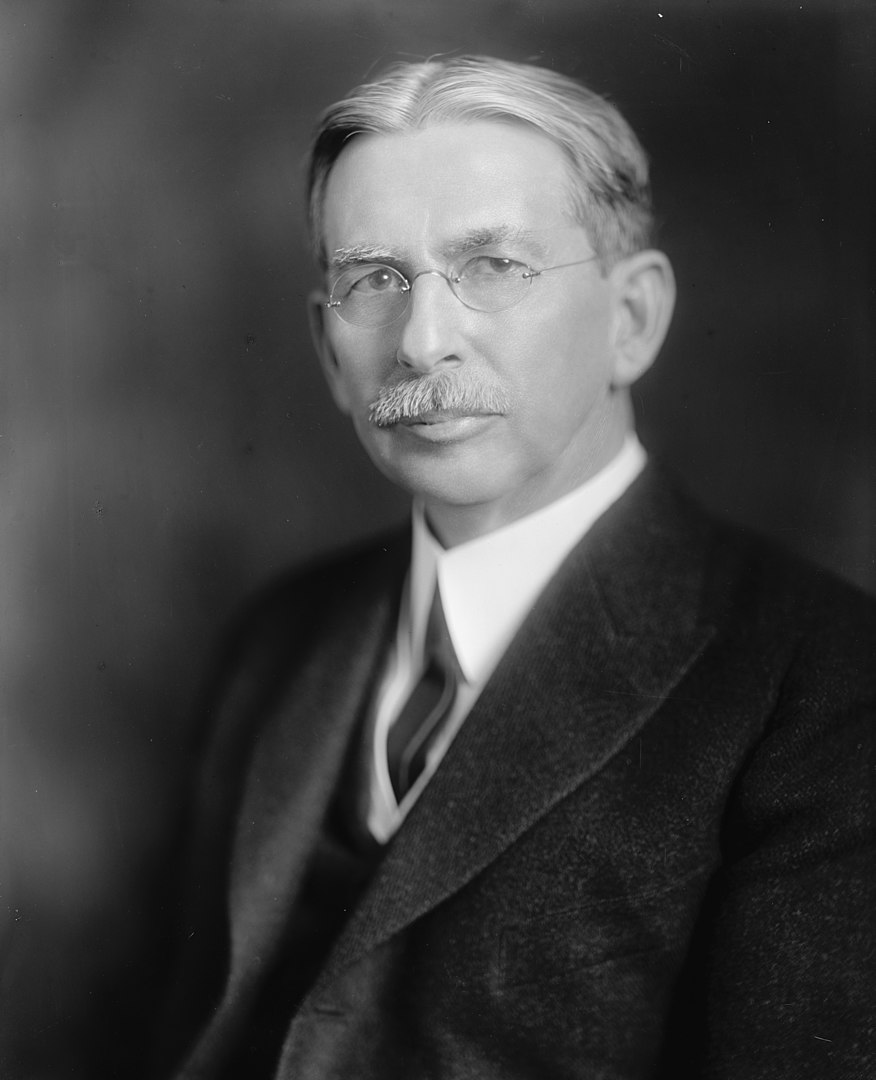

After their first choice turned down the offer because he thought Springfield was too podunk for his liking, they settled for their next option, and little did they know that he’d turn out to be a renaissance tool man. That person turned out to be a young precocious machinist and inventor named James Hartness. Born on September 3, 1861 in Schenectady, New York, he already had experience from cutting his teeth working in machine shops in Connecticut since he was a lad, and used his know-how and indefatigable optimism to flip the company.

On his first day on the job, he decided that manufacturing so many different things was stupid, and declared that from that point onwards, J&L would only manufacture one thing; the eponymous Hartness Flatbed Turret Lathe, which he invented himself – the machine could shape wood, metal, or other materials by means of a rotating drive which turns the piece being worked on against changeable cutting tools.

The business decision was simple, extraordinarily effective, and a little bit revolutionary – something that seems kinda peculiar nowadays; manufacture a single item, and be really really good at it. And given Hartness’s subsequent rap sheet, it seems to work – and became inherent to the novel format.

Other turret lathe models existed, but Hartness’s was by far the most efficient – being able to mill and shape practically all lengths of metal and could combine multiple tasks with higher precision and longer cuts. It was so good, that it was nicknamed “the silent salesman”.

He also benefited pretty serendipitously from his invention, earning $1,000 a year plus a $100 bonus for every turret lathe the factory sold. Some weeks, he was bringing home more money than most Vermonters were making in a year. Hartness also gained a reputation for continuously advocating for better working conditions and more efficient company management to ensure the business would be as successful as possible. But he wasn’t unscrupulous. He also gained a reputation for pushing for the dignified treatment of the workers, which seemed a little bit weird then at a time of historic emerging social class strife, and still seems a little strange presently, in a modern America where the opposites our past generations fought to improve are becoming the norm again.

Hartness’s brilliance, though, came from the fact he didn’t just invent things, he sort of invented new versions of people and their latent talents. And that just happened to jive with his ideal of a company sticking to producing a single product to thrive.

For example, Hartness saw prospect in and hired an engineer and inventor named Edwin Fellows, who developed a machine that would accurately cut gears that he named a Gear Shaper. Hartness spun off the Fellows Gear Shaper Company in 1896, with its namesake operating as its manager. Fellows’ innovation would then opportunely overlap with the rise of the automobile industry a few years later.

After Fellows left J&L, Hartness needed to seek an engineer to replace him. He found William LeRoy Bryant, a student at the University of Vermont, who joined J&L in 1897 as a draftsman and worked closely with Hartness on the cross-sliding-head turret lathe, which is where Bryant took an interest in grinding. Building on a J&L lathe that used a chuck — a specialized type of clamp to hold a piece in place while it was shaped and bored — Bryant developed a new chuck that was both easier to use and more accurate. By 1909, Hartness conjured up another spin-off: the Bryant Chucking Grinder Company. And this pattern continued.

When Hartness hired Fred Lovejoy to replace Bryant at J&L, Lovejoy became an expert in small-tool design, and he eventually created interchangeable cutters that could be swapped in and out of machines. In 1916, Hartness provided the startup capital for the Lovejoy Tool Company, which awesomely still survives and operates in Springfield!

In 1912 Jones and Lamson acquired Philadelphia’s Fay Machine Tool Co, which made the Fay Automatic Lathe – which was designed for the automatic turning of work held between centers. The lathe was significantly improved by a team at J&L led by Ralph Flanders that would be so victorious, that it would ironically eventually evolve into the creation of CNC, which made the manually operated lathe obsolete because the new ones could now operate all by themselves.

Hartness and his prowess fueled Springfield’s combustive growth from the turn of the 20th century until well past World War II, and he did it by introducing one auspicious product after another, each named for its creator.

Because of this, Springfield astonishingly became the machine tool capital of the world.

However, in 1919, Hartness would break his own rule for the only time, when he collaborated with engineer, arctic explorer, and Springfieldian Russell Porter – and invented the optical comparator, a device to precisely measure screw threads that are still manufactured today – it’s so efficient, that any parts that are inspected can be magnified over 200 times, making the smallest flaws detectable!

Hartness and Porter’s mutual fascination with astronomy partially inspired this quantum leap, which is why Hartness wanted Porter to run the comparator business, but Porter was interested in literal bigger heights and decided to instead move to California, where he helped design the Palomar Observatory telescope, so in a rare move, Hartness decided to keep the comparator division close to his side in-house at J&L.

But before Porter departed, he and Hartness also founded The Springfield Telescope Makers – a club that operates in an accidentally trademark pink clubhouse atop Breezy Hill. The story of its standout color is, basically, when it was first built, its enthusiastic members were broke – so they went around to area hardware stores and asked if they’d donate some paint. They ended up with three gallons of barn red, two gallons of white, and a gallon or orange – which they mixed together and got hot pink, which is now emblematic. The clubhouse was christened Stellefane, which is Latin for “shrine to the stars” and not something that you can wrap your leftovers with, is now a national historic landmark, and is still home to both the club, and the annual Stellefane Convention of Amateur Telescope Makers.

Being an avid pilot – one of Vermont’s first – Hartness became president of the Vermont Aero Club and donated land for Vermont’s first airport – Hartness State Airport – just north of Springfield, and had his pal Charles Lindbergh even stop by for a spell in 1927 after his world flabbergasting trans-Atlantic flight. He also served as governor of Vermont for a single term, from 1921 to 1923, but didn’t run for reelection after realizing that Vermont’s rural and poor economy of the time just wasn’t ready for his aims to further industrialize the state. He would die on February 2nd, 1934, and Springfield’s reliable factories became reverberating manifestations of the American dream. Until they didn’t.

This is a surreally enjoyable upbeat clip from a vintage informational film about the concerns and potential disasters of a dwindling economy after World War 2. At the 5:00 mark, the film showcases Springfield AND the Jones and Lamson Factory! Give it a watch – it’s pretty neat! You can get an idea of what the factory, and the town itself, used to be like in the atomic age!

So, what went wrong here?

After Hartness’s death, Jones and Lamson continued to absolutely thrive and continue to become the industry benchmark for their craft, and was considered the zenith of Springfield’s enterprises, employing anywhere between 3,000-4,000 people for most of the 20th century.

So what exactly is the culprit for J&L’s, and Springfield’s, event horizon? Well, that’s a tumultuous conversation, because there isn’t just one thing at play, a lot of circumstances kinda just started to materialize on the scene and began shaking hands with one another – all contributing to Springfield’s ode to its fall-through.

Some locals point fingers at the machine tool unions, who in the 1970s, began to row with the companies about ensuring higher wages for their employees, and would hold a few long strikes to get their point across, something that, evilly, is sadly still being fought for today.

Another reason might be something that’s also been steadily plaguing America since around that time period – outsourcing jobs for cheaper labor costs. Many of these companies were family or locally owned, and when next-generation kin wasn’t interested in taking them over due to the more independent/free-spirited culture that was emerging, they were purchased by larger outside firms starting around the 1960s, which seems to be the beginning of Springfield’s ratchet blues. Detached management started to give the machine tool factories less control and began to fracture the former tight-knit inner communities.

But the bigger causality might just be the companies’ refusal to be self-aware. Japan had been studying American machine tool know-how and began to enter the market themselves – and they did so by dramatically innovating their products.

Around the 1980s, the Japanese hustled billions of dollars into the research and development of computerized machining centers that were faster, more accurate, no longer required a human operator, and cheaper than a J&L turret lathe. Back in Springfield, the factories were sticking to their traditional course, and while they were still making quality reliable machines, they began to become outdated in the new frontier of the trends, and eventually, obsolete, as the market shifted to foreign products that were offering more convenience for a cheaper purchase. I know “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it”, but unless these new fads aren’t just impractical enticements that won’t be good in the long haul, if you refuse to innovate and stay at pace with the competition, it can be a guaranteed ticket to extinction.

Unfortunately, that’s what happened to Springfield.

What’s stressful is that, to be innovative, sometimes that takes substantial amounts of funds, and then, the wisdom just where you want them divested, and for smaller operations, that can be tough decision making, and sometimes, even a fatal conclusion. Hartness certainly had a special knack for it, so much so, that it was said that one bank eventually refused to give him any more loans because they thought he was too creative! I mean, Hartness would amass a little over 120 patents in his lifetime…

Jones and Lamson would be bought by a few different companies starting in the 1960s, and eventually go bankrupt in September 2001, but, the assets were sold to Bourn & Koch Inc. who coolly still continue to supply replacement parts for the extant J&L machines today. However – the optical comparators division of Jones and Lamson, called J&L Metrology, still exists! They’re the only company making optical comparators today in the United States, and are still headquartered in Springfield – attached to the ruins of the rest of the J&L empire (well, after moving to South Carolina for a stint but then coming back)!

The only other stalwart to exist from the ruins of the machine tool era is the Lovejoy Tool Company – who also still operate in town!

A good portion of the old Fellows Gear Shaper factory compound still exists too, and it’s been thoughtfully renovated into mixed commercial and industrial spaces – which is absolutely a preservation win!

Another vestige of that age is the incredible Hartness mansion itself, which has been turned into a bed and breakfast (and at the time I’m writing this blog post, is up for sale according to Yankee Magazine). I’ve visited before and was excited to investigate the house’s most curious feature – an underground telescope connected to the house by a secret tunnel that also lodged Hartness’s private underground laboratory that’s now a museum to Mr. Hartness, The Stellafane Society, and Russell Porter. Man that was cool! Even today, there are rumors that still persist that Hartness built more secret tunnels and even secret rooms that branch out underneath Springfield that have been sealed up, or kept clandestine.

The Jones and Lamson factory had been abandoned since 1986, and for decades, its ruins became a conspicuous landmark that marked one of the main entry points into town. And it was an absolutely gigantic property: 270,000 square feet of decaying building that sprawled over 12 acres of land between the Black River and VT State Route 11, known as Clinton Street through that part of town.

In 2004, the Springfield Regional Development Corporation purchased the property in hopes to, well, do something with it, but its runaway deterioration and designation as a brownfields site – or – a property that’s enormously polluted by toxic materials, usually as the residual of former industrial use, kinda problematized any headway that could have been made. The old J&L factory played host to tons of industrial chemicals, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs); trichloroethylene (TCE); and light, non-aqueous phase liquids (NAPLs), and to remediate hazards like those, you need to secure lots of capital and involve lots of bureaucracy.

In November of 2021, cleanup grants had been secured, and the factory was demolished, which I can’t help but be pretty bummed about. What a shame, it was such an irreplaceably neat building that I feel had the potential to morph into a great new resource for Springfield if given the love.

But – the plan is that they hope to sort of go full-circle with the lot, and lure another industrial gig to town that hopefully will continue to push back the boundaries of the unknown and isn’t just another awful Dollar General. The land is flat, which is pretty a valuable deal in Springfield because most of the village is built up around low-profile slopes that contort around the Black River. It’s also apparently hooked up into some of the fastest internet connections in all of Vermont, which is also a huge deal here given the state’s notoriously lacking rural infrastructure. It’ll be interesting to see what comes along – and I really hope that it’ll be something that will serve Precision Valley with dignity for another century. Springfield is absolutely a town worth rooting for!

An interesting side note to all this, is that because of the rich industrial history and current fading ghosts of the area, the town has kind of amassed a bit of a steampunk scene, which has since turned into a notable cultural festival.

Acreage

I was excited. I was meeting up with a friend from college I hadn’t seen in years who was getting ready to move out of state, so we figured an explore was a good way to part ways. And it was a lovely early fall afternoon – light jacket weather and foliage just barely starting to change into its death hues – the perfect adventuring weather. It had been a while since I’d had a good urbex – my soul was really jonesing for this excursion.

Finding a place to park that we hoped wasn’t suspicious, we casually made our way down the sidewalk, and then made a dash for it. The factory grounds had grown wild, and the brush was almost like it was alive – clinging and scratching with every tendril available, as we hastily stumbled our way towards the tall metal smokestack that marked the factory’s personal powerplant. We figured we’d start in there via squeezing through a hole in the door, and work our way over to the main factory building after. Man I’m glad I’m still a scrawny dude that can wiggle through holes in the walls and broken windows.

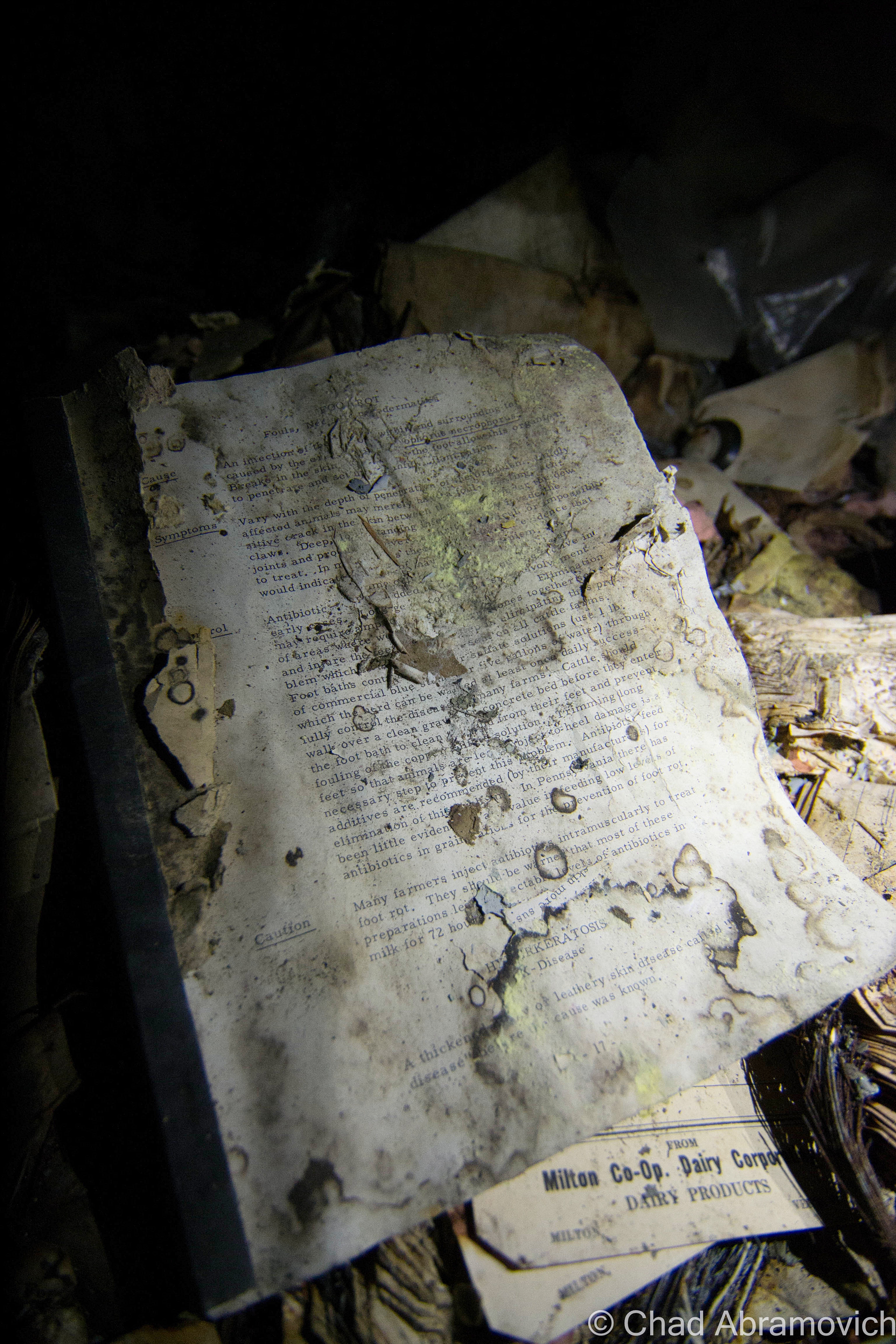

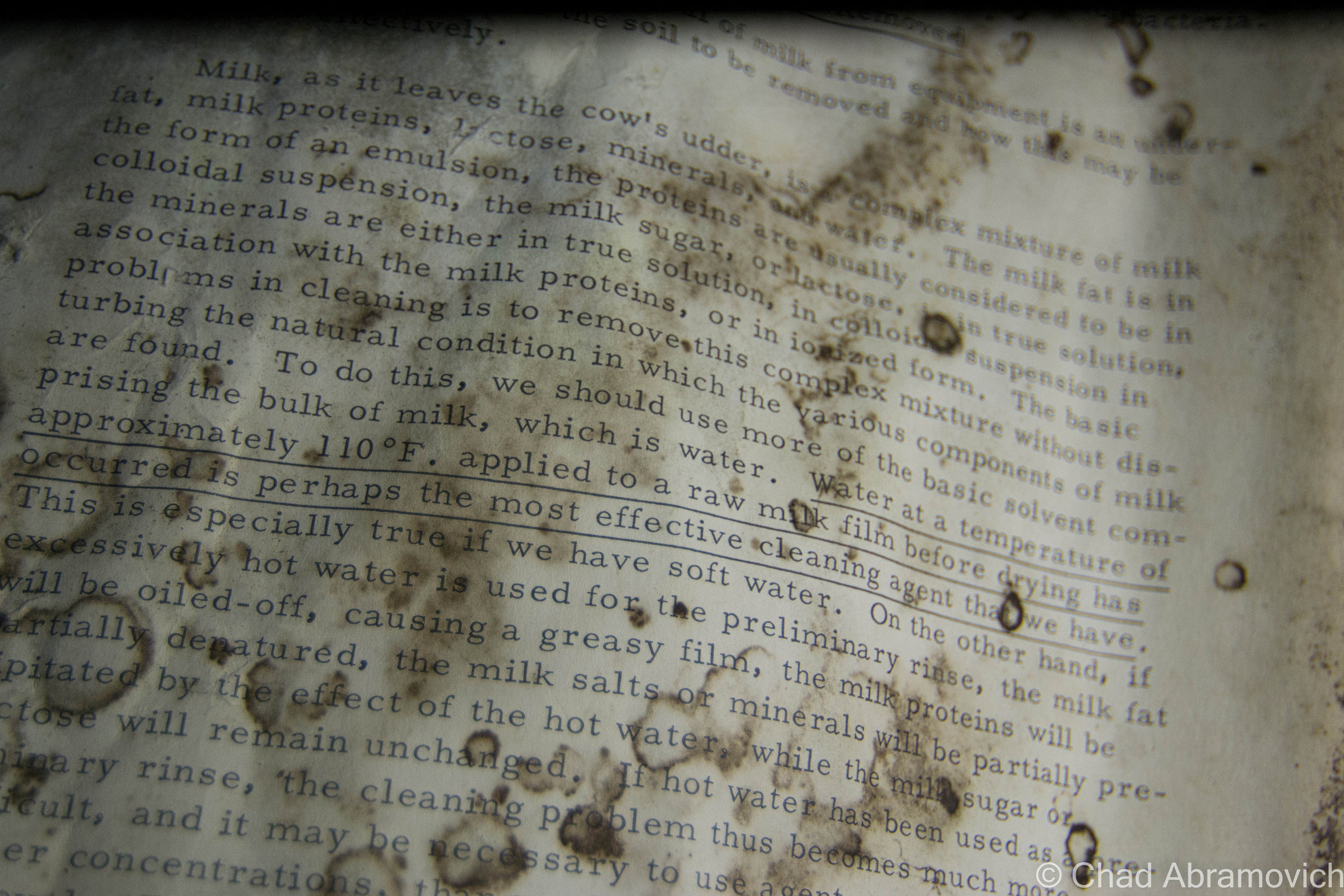

The power plant was a real unexpected treat, and my favorite portion of the grounds that we saw that day. Unlike the main building, the generating station had most of its goodies still contained within drifting dust creating its own little universes in envelopes of light that scattered around the brawny boilers that were from an era that built things to last, and scores of gauges. Floors with hummocks of lead paint flakes and dirt. Desks and chests of drawers were still cluttered with miscellany and workshop brick-a-brack. This was definitely a pleasure to point my camera at.

Afterward, we entered the jungle that has consumed the back fringes of the main building – found our way down a forgotten concrete staircase that was being slowly crumbled by encroaching trees that we were constantly shielding from smacking us in our faces, inside an outbuilding that had totally fused with nature, and contorted through a broken window.

We wandered around for close to 5 hours and still didn’t see everything! The insides of the main plant were cavernous spaces infiltrated by glorious natural light that descended through awesome sawtooth roofs – a design I absolutely love. Lead paint, asbestos, and whatever mother nature blew inside lazily fell like snow, and nature was doing what it does best; reclaiming its territory. Trees and creeping vines had interestingly taken root on the roof and the grounds were thick with vegetation – vines fell down through busted sawtooth windowpanes and tendrilled into the atmosphere. A century of adaptations, renovations, and subsequent deferred upkeep had created a fantastic accidental pastiche on old bricks and steel girders.

Some things sagged down in fatigue, and other verdant things thrust upwards and willing. It seemed the new trees and vines almost created a muted cacoon within, where time oddly stopped and there were only wonders, a vacation world that we could borrow for a while. Strange audio hallucinations fell in all directions, and shadows waltzed behind steel beams and checkerboard walls of broken glass. Though I guess I was a bit disappointed I didn’t find a rusty old Hartness turret lathe still within, this explore was so much fun! (There IS, however, – a Hartness Turret Lathe on display at the American Precision Museum in Windsor!)

There was a tiny portion of this massive complex that was still an active business, J&L Metrology – the last remaining morsel of the greater Jones and Lamson enterprise. Their really utilitarian and ugly wing appeared to be added on much later – and it was something that I made a note of as we pulled into town hours earlier. The two spaces were divided by the original exterior brick wall, but there was a connecting pair of double doors that allowed whoever was at work over there inside the abandoned portion of the building, and that’s exactly what happened.

Just as I was snapping a few photos of some kind of rectangular cavity in the concrete floor that had long been turned into a pool of rainwater and who knows what else, those doors burst open, and some guy powerwalked into the abandoned factory with the trajectory that communicated he was on a mission – a mission that was suddenly interrupted by me.

His boots literally skidded to a halt on the gritty floor, snapped his head to his left, and gave me an appraising and surprised look through a squinty demeanor, then angrily huffed; ” Are you supposed to be in here?” I turned to look at my friend, who was still as a statue, turned back to the man, and decided that answering honestly was my best option, so with a shoulder shrug, I called over “I mean… probably not?” He just glared at me in a kind of tense silence, before pursuing his former mission – and stomped off deep into the huge spaces of light shafts and rusty steel. We both knew that was a good sign that we should leave, and we bolted.

I’m disappointed that I never got a shot of the front exterior of the factory to include in this blog post, but I think there was some re-paving going on out front that day, and we were more focused on leaving before the cops were called on us. Unfortunately, I procrastinated a bit too long and never made it down to get that shot before the demolishing.

But something I did get to see, was Hartness’s aforementioned personal Equatorial-Plane turret telescope back on a rainy and humid June afternoon of 2015!

The rotating green turret rides on rollers supported by the white concrete structure, and it’s also where the stainless steel telescope tube with its ten-inch achromatic objective is installed, which is a modern upgrade to the original. Hartness developed the optics of the telescope to pass through a lens in the wall of the dome, which allowed him to stay warm in Vermont’s brutal winters.

The funny-looking protrusion is in front of Mr. Hartness’s stately former home – looking exactly like something a venerable turn of the last century tycoon would dwell in. At the time, the hotel offered free tours of the telescope and tunnel, no reservations needed, but because the property is currently a real estate listing, I’m not sure if the telescope is closed to the public or not, but absolutely hope that this treasure will continue to be shared with all the inquisitive.

I’ve always been someone that has loved human ingenuity and the magic of camaraderie, so this post was a lot of fun to research and write. So many amazing things happened in this era of America from the genius of common people that I just find so remarkable – and a little bittersweet thinking that we may never have another country-defining boom quite like it.

The earth is kinda played out, so it’s amazing that these strange new frontiers and discoveries can still be made in places like this that were once mapped, and then been forgotten.

For your consideration:

The Vermont Historical Society is one of my favorite organizations in the state – and they have a few nifty videos that briefly chitchat about both James Hartness and The Precision Valley. I’ve linked them below!

There’s a terrific archived article on Mr. Hartness, Springfield, and Jones and Lamson from Mechanical Engineering Magazine thanks to the Wayback Machine!

Are you wondering how a J&L Turret Lathe works? I was able to find a really cool dual brochure and scanned instruction manual from 1910 that includes illustrations!

Since 2012, I’ve been seeking out venerable examples of Vermont weirdness, whether that be traveling around the state or taking to my internet connection and digging up forsaken places, oddities, esoterica, and unique natural features. And along the way, I’ve been sharing it with you on my website, Obscure Vermont. This is what keeps my spirit inspired.

I never expected Obscure Vermont to get as much appreciation and fanfare as it’s getting, and I’m truly grateful and humbled. Especially in recent years, where I’ve gained the opportunity to interact with and befriend more oddity lovers and outside-the-box thinkers around Vermont and New England. As Obscure Vermont has grown, I’ve been growing with it, and the developing attention is keeping me earnest and pushing me harder to be more introspective and going further into seeking out the strange.

I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to keep this blog going. Obscure Vermont is funded almost entirely by generous donations. Expenses range from hosting fees to keep the blog live, investing in research materials, travel expenses and the required planning, and updating/maintaining vital tools such as my camera and my computer. I really pride and push myself to try to put out the best of what I’m able to create, and I gauge it by only posting stuff that I personally would want to see on the glow of my computer screen.

I want to continuously diversify how I write and the odd things I write about. Your patronage would greatly help me continue bringing you cool and unusual content and keep me doing what I love!

Do you have any stories you’d like to share? Know of anything weird, wonderful, or abandoned? Email me at chad.abramovich@gmail.com