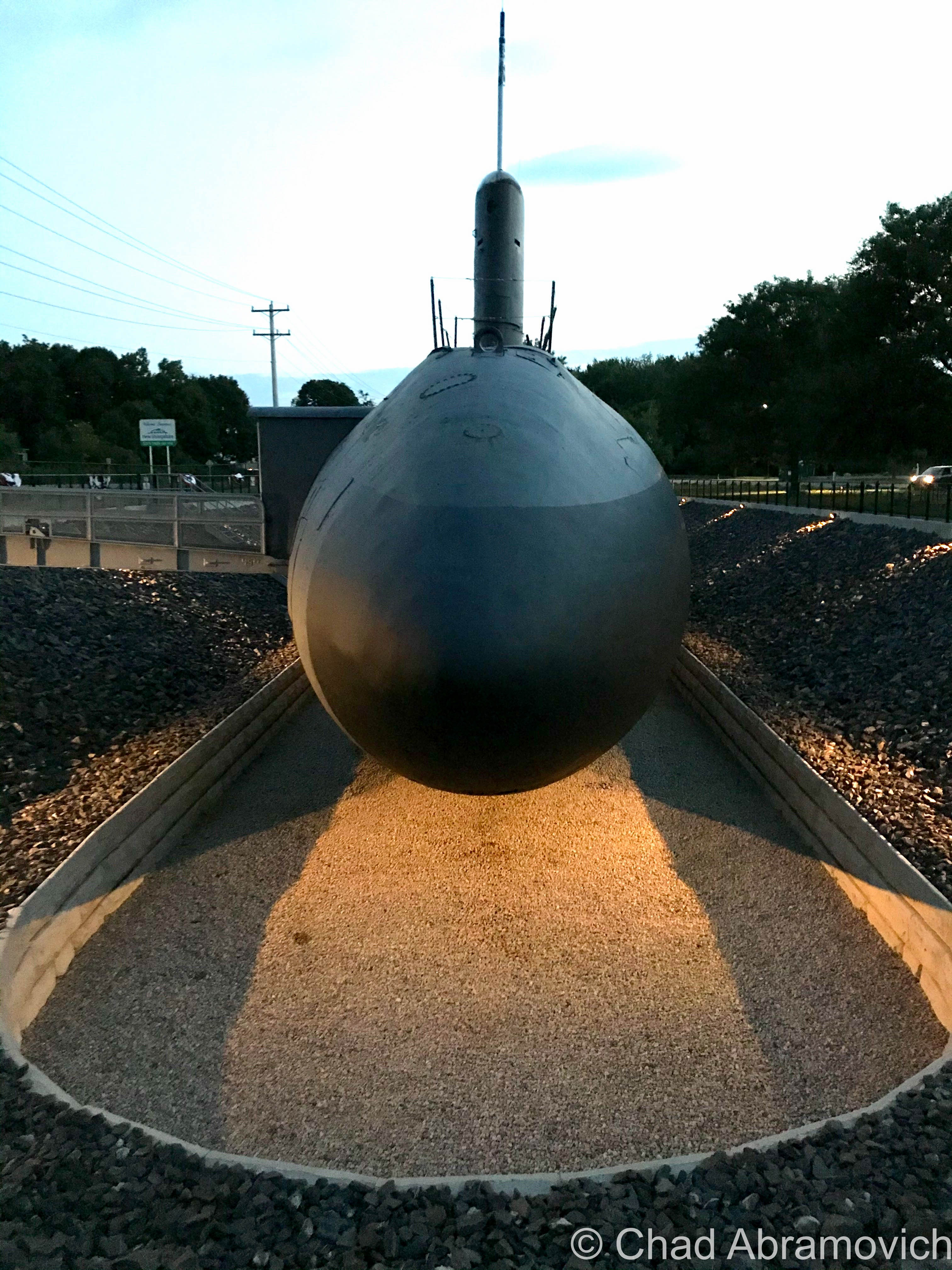

I remember first passing this ugly hulking blight as a young kid on a trip to Connecticut, and never forgot it. It took me until the past few years to really investigate it, though, because I assumed it was just going to be a boring empty building enclosing rows of old stadium seats. But damn, I really under-estimated the interest factor here.

This place is so incongruous and inconspicuous in contemporary Vermont, that many people are pretty surprised to find it actually ever existed at all. And though it was never a huge success, it was a standout place for this compartment of American culture and ran for most of the latter half of the 20th century.

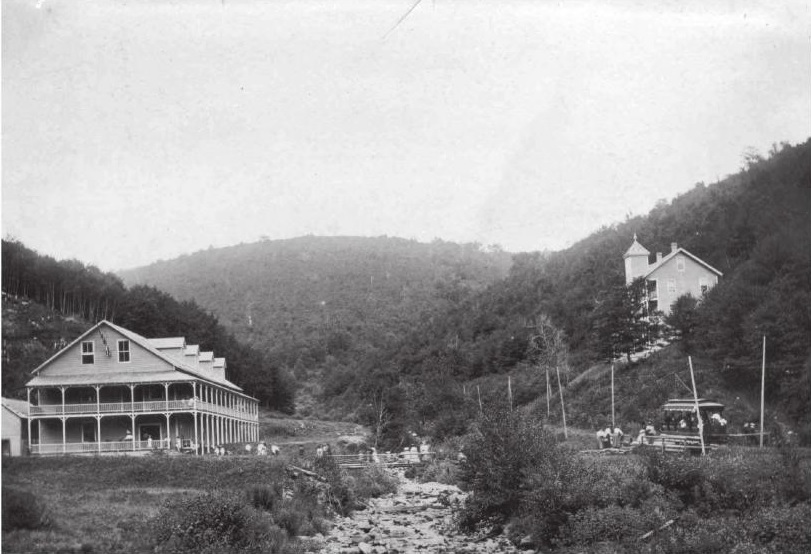

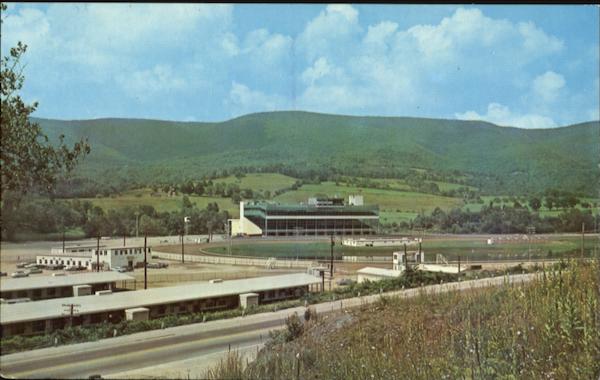

In the spring of 1965, a horse racing track started up in the hardscrabble town of Pownal – where three fascinating mountain ranges, the Green Mountains, Taconics, and Berkshire Hills, collide.

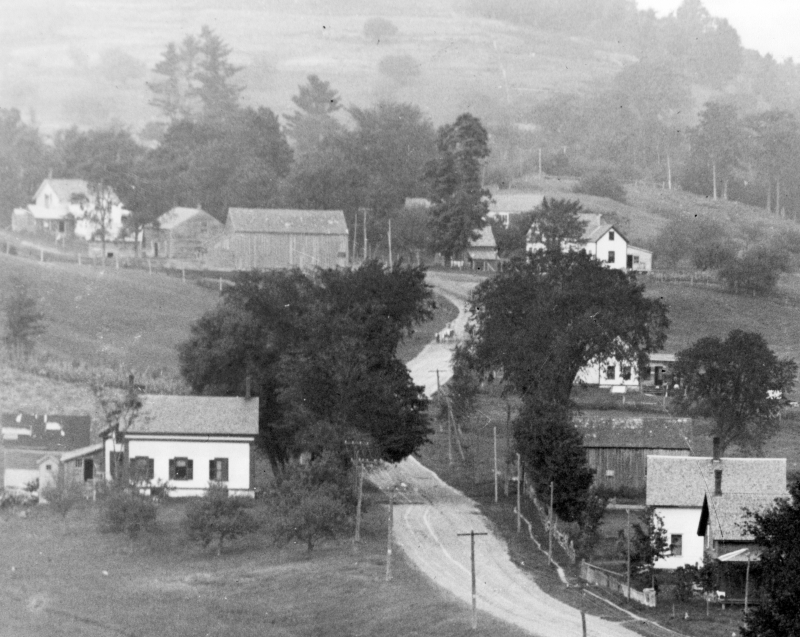

Its three creators’ idea was to duplicate the success of Saratoga, New York, and then compete with it by creating another track in a charming rural area – and the Pownal Valley, which has been literally viewed as one of America’s most photogenic, was chosen.

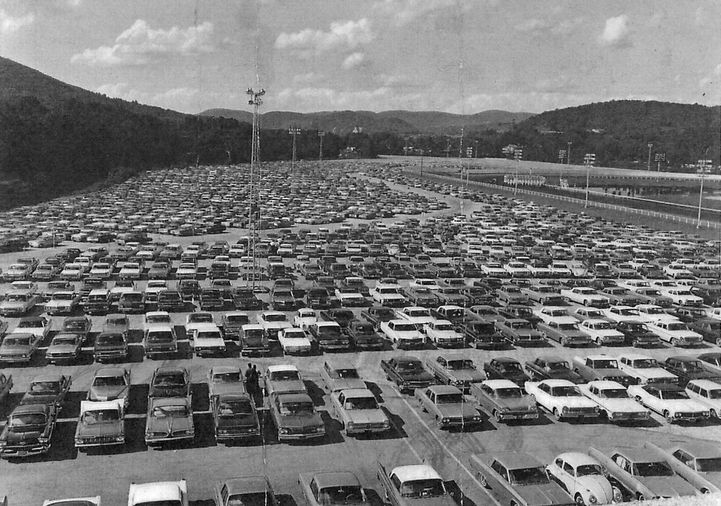

But it was also a very practical decision. Pownal is the extreme southwestern corner of Vermont – bordered to the west by New York State, and Massachusetts and their weird Berkshire Hills to the south. Pownal, being a primary portal into Vermont, is closer to the more urban burbs of southern New England and New York State than the rest of Vermont is, so the track effortlessly racked up a lot of visitors from the “flatlands”.

Pownal’s history is a small magnum opus for yarn spinners and history nerds like me because so much has seemingly happened there, while parts of town look like so much hasn’t happened there, and I’m sure even more tales molder away in the town’s backroad hovels and neat antiquated farms. (Seriously, some environs look like they have been untouched by modern headways – like you’ve stumbled into a deep southern Appalachia, or as my friend calls it; “Pennsyltucky”.)

Perhaps that’s because there’s just something, well, weird about the town, something endemic and enigmatic that might be as old as its mountains, and that draws me in like a torch in search of a flame. The town definitely has a different kind of vibe to it than the rest of Vermont. I really like Pownal – it’s seriously one of the coolest towns in the state! When I sat down to put together my blog post from this explore, I couldn’t think of this old racetrack without thinking about all of the other amazing things that I’ve gleaned about this town over the years.

Originally, the area was inhabited by Mahicans, whose savage fate may have been foretold by prophetic rocks on a Pownal mountainside.

Its realm was the only part of what is now Vermont that was ever trodden on by Dutch colonizers from New York in the 1600s (The Albany/Hudson Valley region of New York has a really cool lingering trace of Dutch-inspired architecture, toponyms, and seemingly ancient muniments as a result! I’d love to do far more exploring/researching there)

What might be the oldest home in Vermont is in Pownal village – The Mooar-Wright House – which was constructed around 1750.

Vermont’s only witch “trial” happened here in the early days of Pownal, where some folks victimized a Dutch widow named Mrs. Krieger for “possessing extraordinary powers,” whatever that meant. The obscure account was originally (and fortunately) recorded by lawyer and historian T.E. Brownell, and has managed to survive into the 21st century, though still pretty obscure.

I’ve read about a few Vermont women who were said to be witches, and usually, the accusations and “evidence” were in the camps of “consorting with the devil” or using “magic”, which lead to mischief like making cows stop producing milk, crop failures, townsfolk suddenly being inflicted by mysterious maladies, and innocuous stuff like predicting the weather before it happens. Other more sinister tales include the conjectured witch conjuring up a vast spectrum of malicious acts towards others she didn’t like.

I’ve been told that my great grandmother could predict the weather, held seances in her parlor, told fortunes she read in tea leaves, and once unwittingly shared a barn dance with the devil himself, but she seemed pretty well-liked and esteemed.

Unfortunately, widows were sometimes the prey of discrimination back then, because they were seen as not only a “burden” to the community, but they were easy targets because they had no family to defend them. Human beings are the real monsters.

Whatever it was that the widow Krieger was doing was seen as diabolical enough to condemn her, and a “safety committee” was organized to deal with it.

The Hoosac Valley: Its Legends And Its History by Pownal-ite Grace “Greylock” Niles tells that the committee sentenced widow Krieger (spelled “Kreigger” in her pages) to trial by ordeal, and gave her two choices. The first choice was she could climb a tree and wait for a group of men to chop it down. If she wasn’t killed outright, she was innocent. Or, she could face “trial by water” – which meant that a group of townsfolk cut a hole through the ice of the Hoosic River, bound her, and then tossed the poor woman into the frigid current. This surefire method stemmed from an old belief that water was sacred, and would undoubtedly sort these provoking preternatural things out. If she sunk, she was innocent, but if she floated, then that meant that she was in allegiance with the devil or some other variety of evil, and would have absolutely nothing to do with science/physics. I also noticed the confirming circumstances of the two methods contradict one another (if she wasn’t killed, she was innocent, versus if she was killed, she was innocent. What).

The widow Krieger chose the latter, thinking it was the safer choice, and sank like a stone. That was apparently good enough for those Pownal-ites who gathered for the show. Unlike neighboring Bay State witch hunters, though, these Vermonters seemed to be a bit more philanthropic, and a group of men suddenly panicked and scrambled down the riverbank to fetch her. Not only did she live through the ordeal, but I’m assuming things were really awkward afterward. As the committee resolutely said afterward; “If the widow Kreigger had been a witch, the powers infernal would have supported her”

Today, there’s a standout cliff near North Pownal that local parlance still knows as “Krieger Rocks” – both a homage to early Dutch influence and an informal parable of a hapless woman.

I also found this occurrence even more uncanny, because while the epoch of the infamous witch hysteria of Salem and southern New England occurred in the 1690s, Vermont’s lone delirium happened sometime in the 1760s, probably after 1761 when the town was charted. (Actually, Yankee witch based superstitions, though weakened, remained alive into the 19th century!)

Perhaps Pownal just needed to install a few witch windows?

In October of 1874, Thomas Paddock, a well-respected farmer with an amicable character, suddenly found his property under a maelstrom from poltergeist-like activity.

Stones – varying in size from pebbles to a 20-pound boulder (!) rained down on his house and outbuildings, but neighboring properties were completely unaffected. The stones were found to be hot when handled, even on chilly nights, and a few of them reportedly defied gravity, and rolled uphill, or even up and over the peak of the roof after landing, almost as if they were propelled. Mr. Paddock dubbed whatever it was “the stone-throwing devil”, word got out, and for a brief time, it caused a sensation.

He even offered a reward of one dollar for anyone who could solve these shenanigans, but shortly after, the cache of tourists and newsmen cleared out when the odd activity finally stopped. Nobody was any wiser at what exactly happened at the Paddock farm, not even today (though cursory blame was attempted on a hired farm boy named Jerry, who coincidentally was in the vicinity of the falling rocks more often than not…) Interestingly enough, the farm just happened to be near-ish the Krieger Rocks part of town…

Local girl Addie Card, who once labored at the now-demolished and superfunded Pownal Tannery (a site I’m sorry I missed out on), was photographed by the now-famous documentarian Lewis Hines and the image became a barometer in his efforts to stoke public objection about turn of the last century child labor in America. A collection of dilapidated shacks off state route 346 on a dented dirt drive known as “French Hill” are original tenement houses of the old tannery and one of the last reminders that the place actually existed in North Pownal.

There’s still an existing and forgotten granite tri-point state marker erected by surveyors in the 1800s that’s now lost in the thick forests of the hills – some of those slopes still cooly contain colonial-era scrawlings on glacial deposited boulders of predecessing hikers and explorers – just some of the many relics I’m sure these hills contain. I know some people that hit a jackpot with their metal detectors around it. Who knows what else can still be found within the southern Green Mountains?

Another notable person with alleged wild talents was Clara Jepson, Pownal’s official seer – a profession that you don’t hear that much of in contemporary times (except maybe advertised on television at 3 AM). But until she died at 87 in 1948, she was the best-known clairvoyant in Vermont and created a pretty venerable reputation to back up her accumulated character.

Among her professed talents, she could allegedly hunt the location of lost or hidden objects, and was consulted on several cases, including one of the terrifying disappearances in the nearby mountains that would later become an area known as the “Bennington Triangle” (one of my favorite Vermont stories). According to witnesses, her answers would manifest themselves in a cryptic language within the folds of a lacy white handkerchief she would fondle during her sessions. (If anyone is old enough to recall ‘seeing’ her in real-time, or has any kind of story related to, I’d love to hear from you!)

It seems like Pownal’s always done things a bit differently, in ways that seem to almost be a few shades deeper into the mystic that’s masqueraded by a rough enchanting landscape, and maybe that’s augmented because of the town’s historically independent spirit, mountain isolation, and influenced by its border state surroundings. I honestly don’t think that this racetrack project could have happened in any other spot in Vermont.

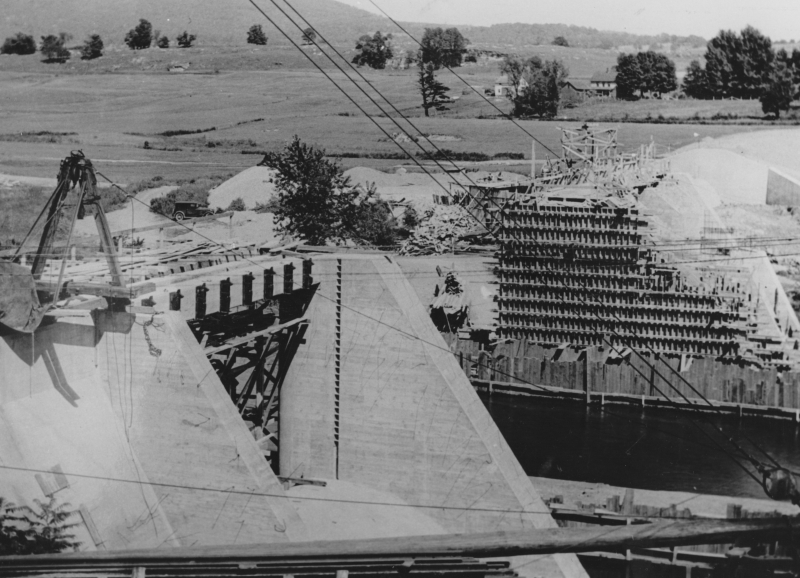

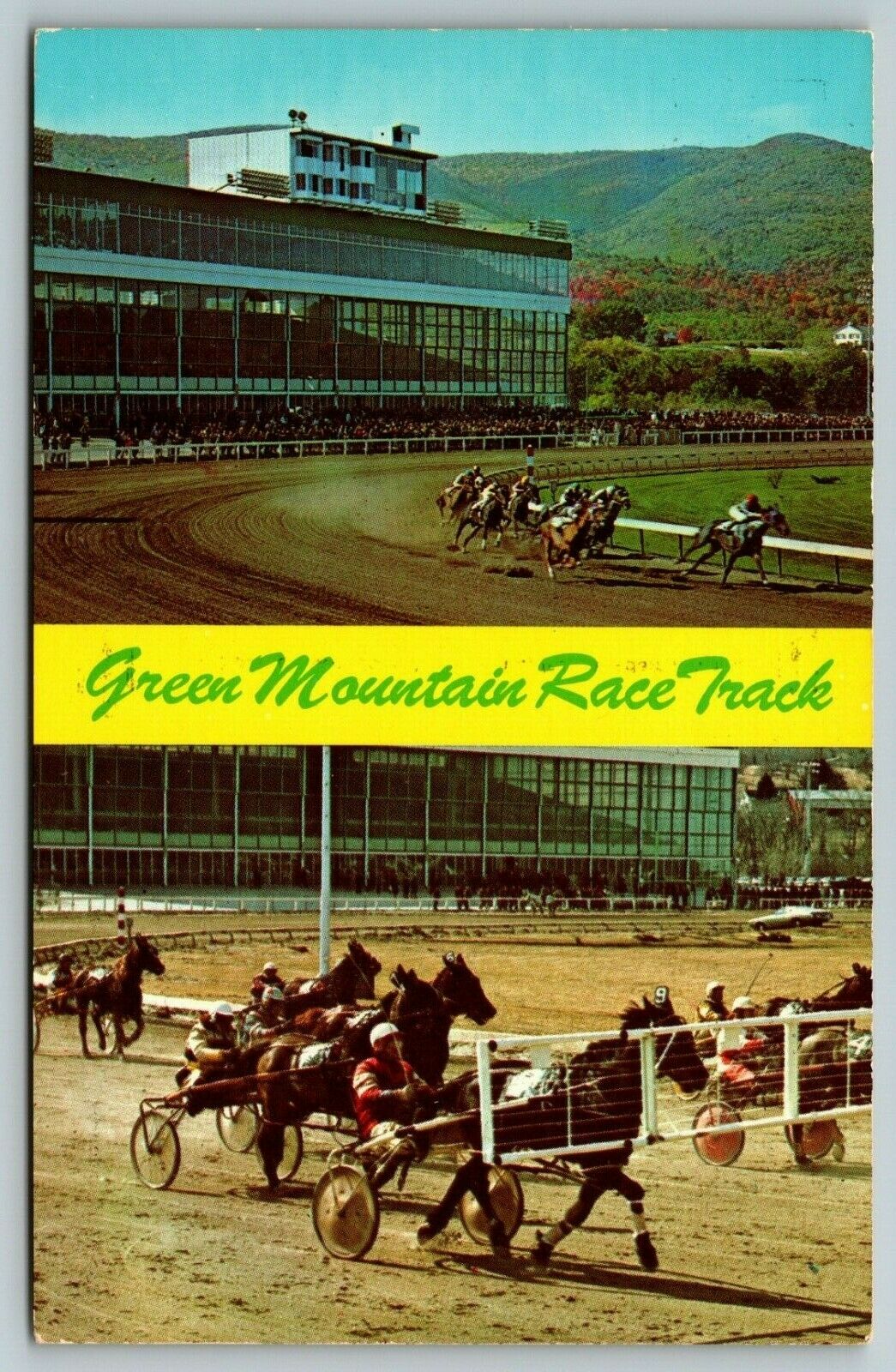

And speaking of the racetrack, it also seems to be the last big spike in Pownal’s histogram, for the time being anyway. The track opened in May of 1965 at a cost of six million dollars in a former cornfield along the Hoosic River.

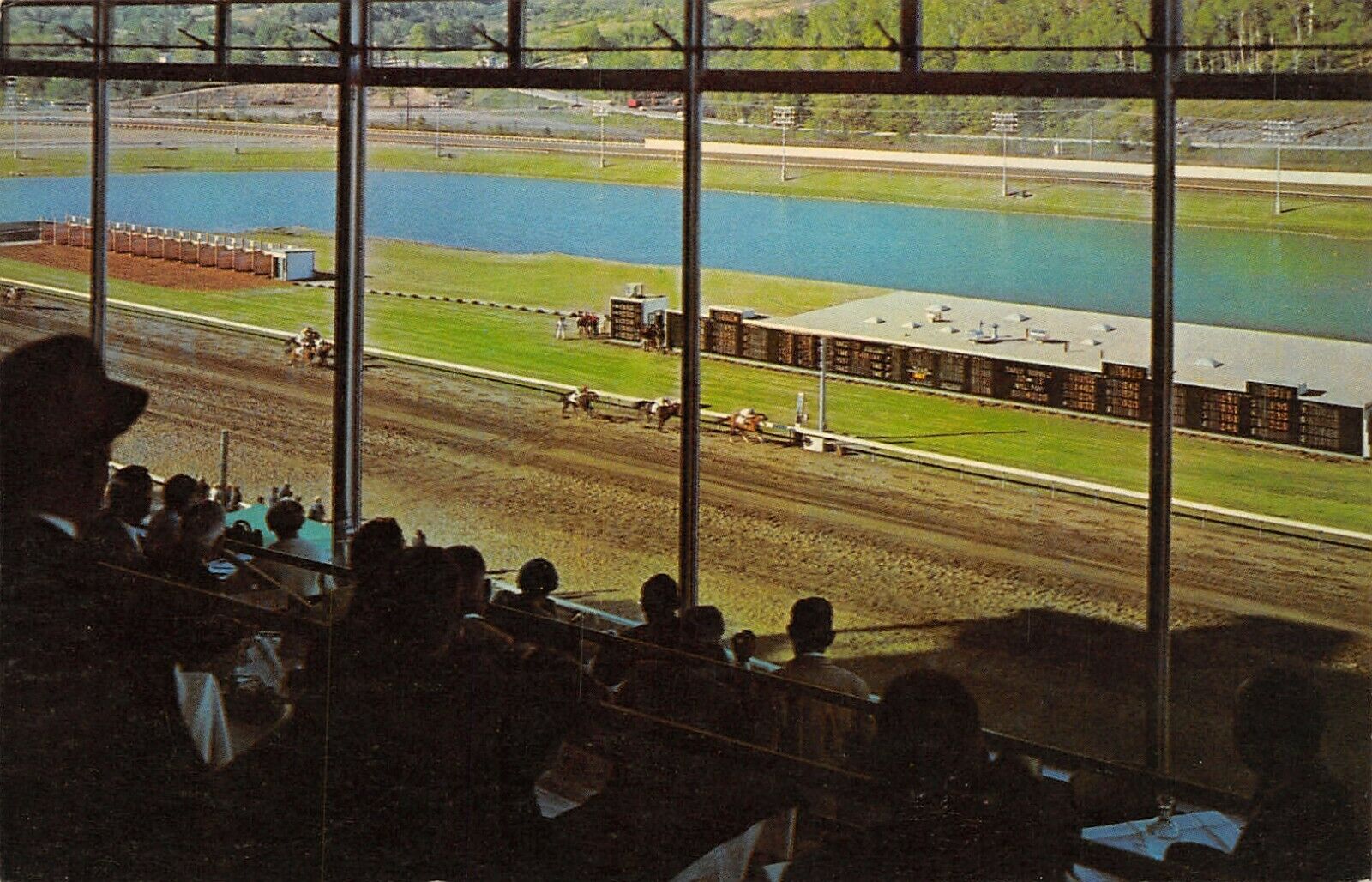

But from the start, Vermont’s only pari-mutuel racetrack failed to draw in the crowds that its investors were anticipating – the actual attendees were half that. But it kept on keeping on, despite quite a few subsequent telltale ownership changes, and oddly became kind of significant for east coast horse racing, ironically because of the efforts made just to keep the place buoyant. It was one of the earliest to do gimmicky nighttime races, and the first to do Sunday matches anywhere east of the Mississippi during the days of yore when the rest of the country still adhered to the blue laws. It created a sort of niche fanbase and wound up employing a lot of locals, which was a boon in a region with an economy that was becoming pretty hard-up. Casual tourists enjoyed the racetrack, too, and I was told it was a popular stop for folks who’d take Sunday drives through the mountains of Southern Vermont.

Twelve years later, horses were dropped from the itinerary, and Greyhound racing was the only thing occupying the oval (which I guess is the bottom echelon of these kinds of places, according to some nostalgia sites I browsed) until 1992, when the track closed for good – in part to animal rights activists, waning income, and the state making the activity illegal. A resurrection was attempted around the turn of the millennium but ultimately failed. It was strange seeing moldy flyers and banners ambitiously announcing its “grand re-opening” stored in soggy piles in the dank basement levels. I’d love there to be more economic prosperity for Pownal and Bennington County, but not in the form of animal exploitation.

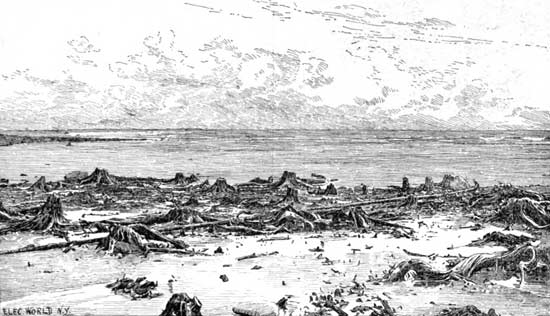

Today, the 144-acre property is abandoned, despite multiple failed attempts to do something with it, and it’s a real shame that nothing has happened yet. Further damage was done when the nearby Hoosic River, a perimeter defining watercourse that wears the Indian appointed name of many local toponyms that variate between “Hoosic” and “Hoosac” – and has a history steeped in local lore – flooded its banks significantly a while back and seeped into the lower levels of the building.

The site has so much potential – especially being off the most traveled road in Vermont. Lollapalooza held their festivities on the expansive grounds in 1996, and a few antique car shows also took advantage of the space between 2005 and 2008, which fits right in seeing as the iconic Hemmings Motor News is located up the road in Bennington in a rad, restored Sunoco station.

Williams College, a few miles south of the old track, even did a study about the property in 2011 and suggested everything from affordable housing, light manufacturing, or bringing back some agriculture.

Until any of that happens, you can’t miss the place. It’s an intriguing, conspicuous eyesore at one of the main entry points into the state – dominating a portion of the view as Route 7 begins to climb the mountains towards Bennington.

One of the biggest curiosities about this property to me was the name of its access road. The unassuming road is named after a cemetery, but I’ve walked around the grounds and I couldn’t spot any boneyards. It made me wonder – back in the day, moving an old cemetery wasn’t as big of a deal as it would be nowadays. Could there have been an old family plot from an old farm that was erased? Are there still corpses trapped underneath the sea of weedy asphalt that encircles the grandstands, or maybe underneath the earth of the old track?

Well, according to Google, the cemetery still exists in a far-flung corner of the property, and it’s the oldest in town – with a gathering of faded and broken 19th-century headstones placed in the woods (Interestingly, Pownal has a lot of cool old cemeteries – and many of them are old farm family plots, which might seem kind of an odd concept in today’s world). I’ll have to give it a visit the next time I stop by.

Many of the glum-looking crumbling cinderblock stables were razed for a solar farm, which is awesome, but the gigantic grandstands building still stood at the times of my visits, and was a spooky but really fascinating time capsule of the late sixties and early seventies, with its cold cement blocks and hideous fake vinyl wooden wall paneling – an architectural design element I hate. I especially admired the extinct fonts on all the office doors; “bookkeeper”, “telegraph”, “photographers suite” etc – that was pretty neat to see. One unifying theme to the property was the use of a particular dark green – thematic of its location in the Green Mountains, which was used on everything from the exterior paint job to the color of its graphic design marketing. The appeal, though, was a little curious. Everything about the place felt cheap and kinda sleazy.

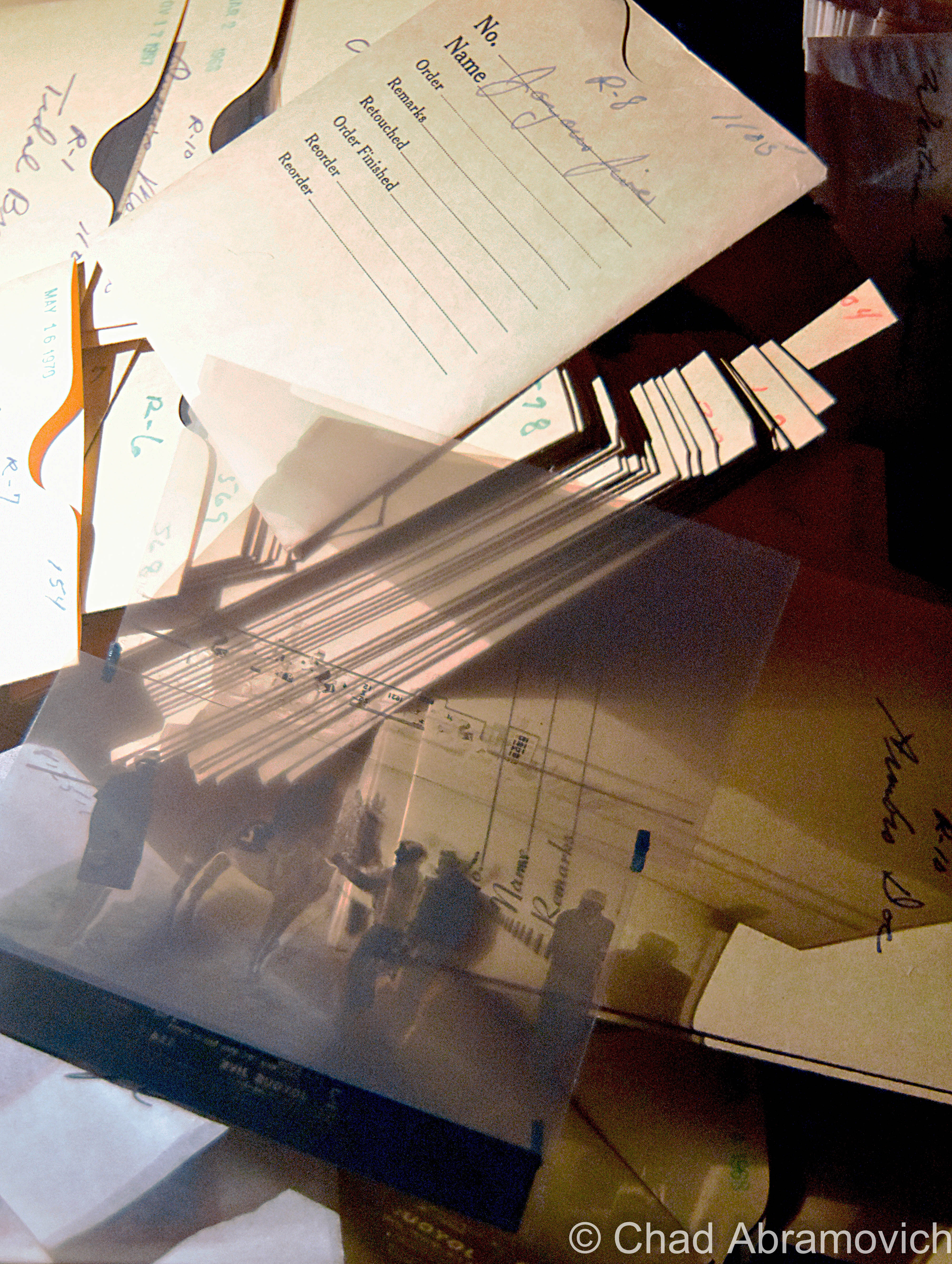

The building was an unassuming labyrinth of smelly and squalid offices and catacombs of dark and drippy maintenance and miscellany areas all filled with relics, gross puddles of goopy chemicals on the floors, and wandering birds. The roof had long failed, and nature has been metamorphosing the structure in gross ways for over a decade. One of the coolest things I found was the former track photographers suite, which was still filled with heaps of developed and undeveloped film of the old races. The basement had such a foul odor that, eventually, we had to dip back outside for some fresh air revitalization.

Upstairs, the former venue, snack bars, and grandstands are all cavernous spaces that have been trashed, smashed to smithereens, graffitied, succumbing to water and decay, and turning into terrariums, as moss and young plants have begun to take habitat on the floors and the rooftop. A whole colony of what was probably hundreds of pigeons had taken up residence on (and within the cavities of) the defective roof and constantly circled the large, mid-century structure.

It was a creepy explore, with lots of eerie sounds that croaked and carried through the wide spaces and dark crevices. The smell of rancid decay permeated everywhere.

Overall I thought this was a real bummer of a place – an attitude formed by the dated and ugly ruins, and the fact I’ve never enjoyed or supported the kinds of revelry that once went on here.

The real reason I chose to make multiple explores here was simply because of the fact that it exists, and my sense of wonder seduces me to explore as much of Vermont as possible – especially the abandoned stuff. And admittedly, a few visits had me appreciating it in a totally different light and discovered that it was a treasure trove of an explore and architecturally evocative of its time. But I found it a real shame that other people who’ve stopped by have decided to completely decimate this place and use it as a law-free zone.

The amount of destruction in the past few years was astonishing – I noticed a humongous difference between my visit in July of 2019 and March 2020, and towards the last months of its life, the bad road tar of the old parking lot and access road almost always had multiple cars – many with out of state plates, parked around.

The people that come here are quite a circus show of other amiable explorers, curiosity seekers, locals, and shady characters – it seems like many out of staters or area hooligans are using the old track as a law-free zone. A few people we ran into definitely made us uncomfortable.

Dusk was humming up, and as we were getting ready to leave, three boys on ATVs zoomed through the parking lot, and a Nissan Altima full of teenagers parked in the weeds in front of the building and had an “oh shit!” moment as we pulled out and all locked eyes as they were removing copious packs of Twisted Tea out of their trunk, while nearby, a young twenty-something couple was awkwardly trying to wedge a sign they had taken into the backseat of their Ford Focus.

I had this post sitting in my WordPress drafts for a while. Because I’m a perfectionist, I wanted to get the feeling right and make this post interesting and fun, but I was also concerned about posting the location. I realize that in the past few years, a larger amount of people have been using my blog to add places to their exploration checklists, and I’ve been really re-evaluating my responsibilities as a preservationist and a local weird worker, what I post, and how I write about it.

I already saw the racetrack morphing into a weird beacon for trouble, and I guess I didn’t want to add to it. Thanks to the internet, nothing is a secret anymore, and I’ve seen an alarming increase in the momentum of special places, in general, being over-touristed and ruined by unlikely people.

Unfortunately, at some point on the night of September 16th, 2020, a “suspicious fire” was started in the grandstands that used the wooden seats for fuel, and the entire building was cooked and even more destroyed than it already was. The fire fueled a local outcry of folks who are fed up with all the fools turned sightseers. This is one of the many reasons why I never give out locations. Practically everything you’ll see in my photos has been reduced to ashes, but the mangled and blackened shell sadly still looms beyond Route 7 looking pretty haunted. If you’re interested, the Berkshire Eagle has some illuminating drone photography of the damage.

I’m so grateful I had the chance to enjoy a few explores and make some fun memories here when I did, and am saddened by the loss of what oddly was such an uncommon wreck. There was so much more that I wanted to see, that now I never will.

I think that the Green Mountain Racetrack was uniquely special. Because of its smooth accessibility, its literal open-door policy intrigued all kinds of souls who decided to let their curiosities lead them here. I was scanning loads of posts on Instagram and was a bit startled to see just how many people not only have snooped around here, but were genuinely fond of this place in their own ways, and had fun making multiple trips here to satisfy the natural human urge of investigation. Abandoned places inspire that kind of magic that encourages us to forget about the chains of society and our inhibitions. When the news hit that this place burned down, people started commiserating.

This was a continued lesson for me not to take places for granted. I was just speaking to a good friend a few weeks ago about planning yet another return here because of all the fun we had last time – but we took this old track for granted, and now it’s gone. Everything is finite.

So here you go; a whole bunch of photos of the old Green Mountain Racetrack!

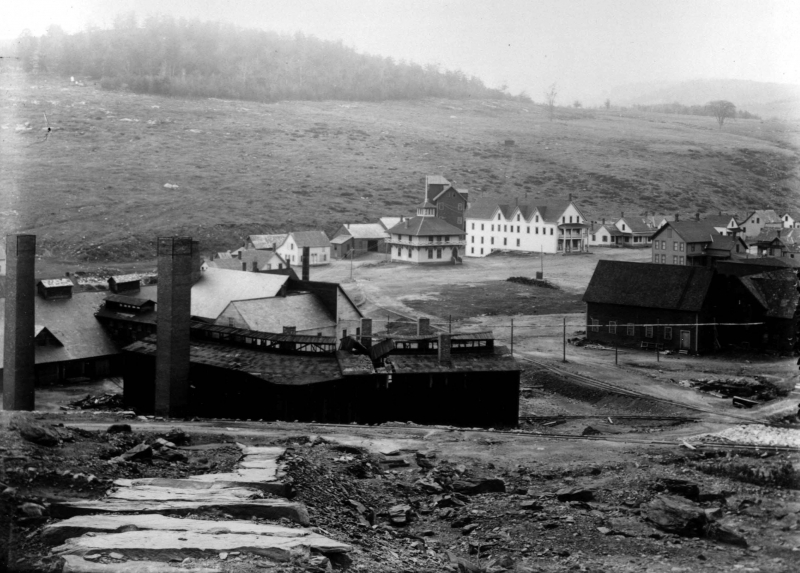

The Green Mountain Racetrack when I visited back in Spring 2011.

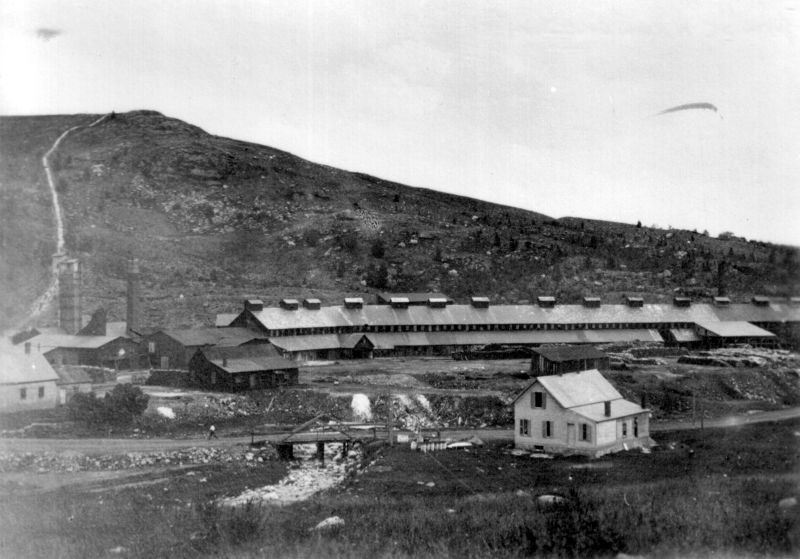

The Green Mountain Racetrack June 2019/March 2020

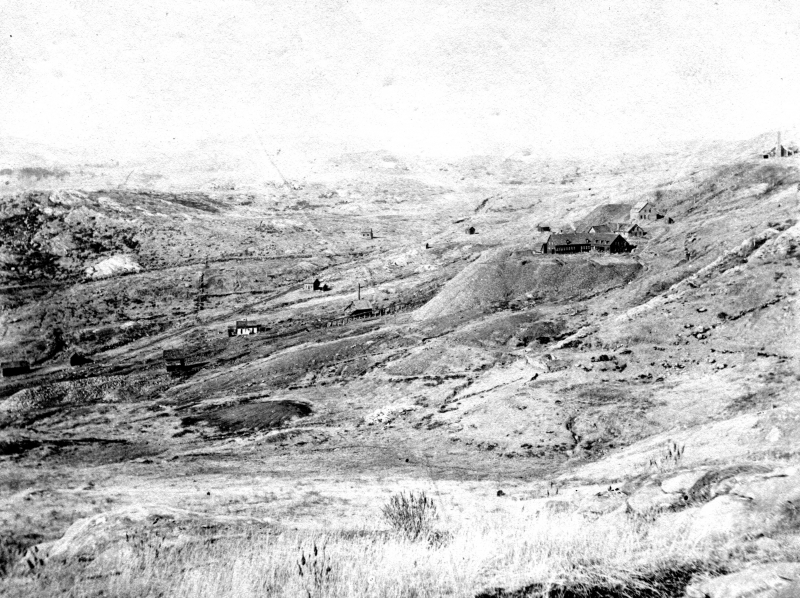

Green Mountain Racetrack June 2020

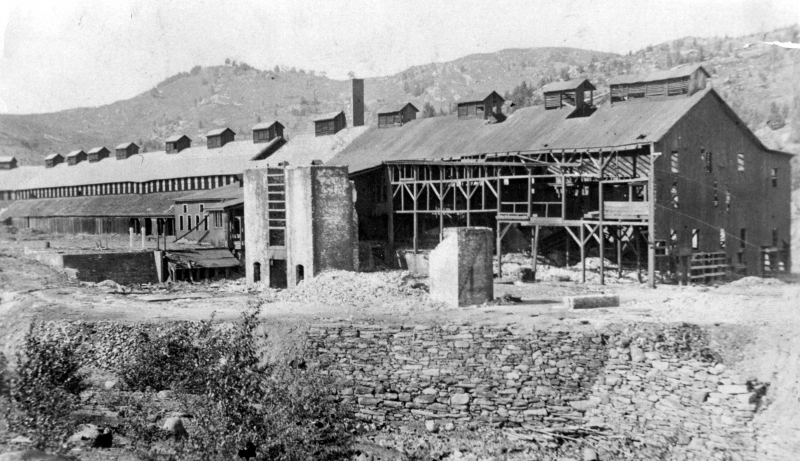

Photos from my last sojourn here. It was a sultry early summer day as mists slid of new green slopes vibrant against gloomy ashen skies and uncomfortable humidity that drenched us in sweat. The entire place reeked of something sodden and foul. It had started to rain, and the roof, which had long failed, was letting fetid water in which dripped down and baptized us and made the upper carpets like stepping on a wet sponge.

“You’ve been baptized – your soul belongs to the race track now” I joked as a trickle of mystery water dribbled down upon my friend’s head and shoulders. She involuntarily cringed at the sensation and shot me a glare.

Man oh man, I really miss this place.

I’d really love to do more shunpiking and exploring around the Pownal area – it really is a gem of a town, with far-stretching vistas, old farms, backroads that convert into gnarly class D forest roads, and hidden swimming holes under mountain cascades.

When I was curiously searching for other people’s media from their explores here, I found quite a few talented folks who bring some great stuff to the table. Here’s one of my favorites; a great urbex video by explorer “Dark Exploration” (who, in my opinion, got wayyy better shots than I did!)

Check out this cool drone footage shot by Youtuber Dagaz FPV! It gives you a scope of just how big the property was and some rad POVs that I couldn’t capture. Maybe I should invest in one of these…

Are you from Pownal or the surrounding environs of Southern Vermont/The Berkshires/New York State? Or are you a Vermonter in general? I’m looking for weird and wild stories, wonderous places, incredible people, and especially abandoned locales! So if there’s something you’d like to share with me, I’d love to hear from you!

I’d also really love to grow this blog and present unique, meaningful, and extraordinary content that’s a departure from the same regurgitated stuff you find everywhere else online, and your help would be hugely appreciated! I have bad social anxiety, so I’m not always on social media as often as I probably should be.

Feel free to drop me a line at chad.abramovich@gmail.com

Also – if you appreciate me and this blog, perhaps consider making a donation at my PayPal below? The pandemic has hit my finances and my mental health pretty hard, so any amount is humbly appreciated. I’m also on Venmo if that works better.

Since 2012, I’ve been seeking out venerable examples of Vermont weirdness, whether that be traveling around the state or taking to my internet connection and digging up forsaken places, oddities, esoterica, and unique natural features. And along the way, I’ve been sharing it with you on my website, Obscure Vermont. This is what keeps my spirit inspired.

I never expected Obscure Vermont to get as much appreciation and fanfare as it’s getting, and I’m truly grateful and humbled. Especially in recent years, where I’ve gained the opportunity to interact with and befriend more oddity lovers and outside the box thinkers around Vermont and New England. As Obscure Vermont has grown, I’ve been growing with it, and the developing attention is keeping me earnest and pushing me harder to be more introspective and going further into seeking out the strange.

I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to keep this blog going. Obscure Vermont is funded almost entirely by generous donations. Expenses range from hosting fees to keep the blog live, investing in research materials, travel expenses and the required planning, and updating/maintaining vital tools such as my camera and my computer. I really pride and push myself to try to put out the best of what I’m able to create, and I gauge it by only posting stuff that I personally would want to see on the glow of my computer screen.

I want to continuously diversify how I write and the odd things I write about. Your patronage would greatly help me continue bringing you cool and unusual content and keep me doing what I love!