For a blog about obscure Vermont, I’m a little surprised that an abandoned farm hasn’t made the rounds in my posts yet.

Every state has stereotypes that give an oversimplified image of what it’s supposedly all about. Massachusetts is all paved suburbia and Dunkin Donuts, Maine has the ocean and fanfare for an acquired taste called Moxie, and Vermont is a bunch of farms and home to Ben and Jerry’s.

Well, in Vermont’s case, that’s not that far from the truth. Vermont is the most rural state in the nation and to prove it, we have a bunch of statistics with the word “small” in them. We have the second smallest population, the smallest largest city, the smallest tallest building, the smallest state capital, and are the 45th smallest of the states.

Growing up in Vermont, your friends most likely fall into two categories. You love it here, or you think it’s wicked boring. Personally, it’s what we don’t have that I think makes Vermont so great. There are no casinos here, no billboards, few malls and chain stores, and no amusement parks (unless you count the Pump House at Jay Peak?). And in all that space in-between our 9 cities are a lot of farms and their variations.

Agriculture has strong roots up here. Generations of Vermonters have been farmers because you did what you had to do to get by. In such a detached state, other jobs often weren’t here so you had to be self-reliant, until very recently with the emergence of the internet and a growing commuter culture. This hardscrabble lifestyle may very well have infused our culture with that independent-minded, self-sufficient ethos, devising that ‘you-can’t-get-there-from-here’ Vermonter who is crusty, stoic and has abundant old school common sense. Stories of old farmers who toiled in the barn all day and then bootlegged whiskey at night to make enough to save their farms can still be uttered by old timers should you ask them about it.

Many surmise that this was the reasoning behind all the Poor Farm Roads that can be found across the state, because so many Vermonters were farmers who lived around the poverty line, but the actuality is more depressing. Poor Farms were institutional farm complexes that were sort of an early form of welfare, created and supported by public taxes, where anyone who couldn’t support themselves would wind up and were made to labor their days away on by doing farm work. In return, they had food, a bed, and clothes. But from what I heard about them – they were often gloomy places, and many unfortunates spent their lives there and went to the grave there. There’s a Poor Farm Road in the town I grew up in, but by the time I was aware of its namesake, most of the place had long been developed by cookie cutter rural suburbia and erased, minus one old barn which the local kids would tell me used to be part of it, and according to them, had bars on the windows and shackles still on the wall. But a trip down to the end of the road as a late teenager revealed it was just a dilapidated barn without the lingering despair.

In the 1800s, historical records say that the state was 3/4 deforested with most of the land used for sheep grazing, and later, dairy – which gave us a more cows than people ratio. Over the last century, that proportion has directly reversed, and now 3/4 of the state is back to being forested, and we now have more humans than cows – though I’m still heckled about that by flatlanders. The trend reversal started to develop during the last century when aggravated Vermonters moved westward for literal greener pastures with less rocks. We lost about half our population then, and a sizable number of towns around the state still haven’t recovered the lost numbers of their 1800 population peaks.

A good example would be the out of the way southern Vermont town of Windham. The town sharing a name with its positional county had over 1,000 bodies, a half dozen villages and 2 post offices in 1820, but by 1970, had a headcount of just 150.

There is a place name on state maps in the town of Sunderland curiously labeled”Kansas” (there’s also a tinier “East Kansas” a mile or so east), and the odd name is said to have came from a curmudgeonly old farmer who in the 1800s, kept making empty threats to his family, other Sunderlandians, and anyone else who’d listen, that he was so fed up with his rocky fields that he was going to sell his farm and move to Kansas. Only, he never did, and died right there in Bennington County. That part of town became known as Kansas by the locals and soon became a wayfinding moniker.

Vermont still has plenty of agricultural affairs left, but with milk prices not equaling the cost of production, dairy is slowly and steadily dying. Farmers are even callously getting flyers with suicide prevention hotline numbers on them in the mail.

But despite dwindling farms around the country, smaller horticultural farms are taking root all over the state and growing – mostly supporting modern-day farm to table fads, which means Vermont’s emerging restaurants and craft breweries can come blazing through wearing the future on its sleeve.

As a kid, I grew up playing in the woods of an old farm behind my house. Most of the land wasn’t tended and had grown up into a mature forest by then. We used to cut 4 wheeler trails through the growth and explore the old farm roads and examine artifacts from yesteryear we’d come across, like old barbed wire fences, a neon green AMC Hornet pushed into a ravine, and the prime find – the grimy miscellany of the old farmers’ junkyard. We used to salvage stuff from the heaps of junked appliances, tires, and barn mementos and use it to build forts with. Old tin, a couch, the front seats from an old Ford Mustang, even an old woodstove. We made some cool hangouts from the refuse we excitedly recycled.

A friend of mine got in touch with me and said she had a new location up her sleeves, an abandoned farm up in the north part of the state, the dumping ground part of it was on her property and she hadn’t gotten around to doing anything about it yet. I thought it was weird that I live in Vermont and haven’t explored a farm yet. So on a beautiful autumn day, I met up with her and she led me through some overgrown tangle woods of nettles, dead apple trees and mangey looking cedar trees that turned the area into a dark entry. A few minutes into our walk and the already fallow landscape began to change, and I began to notice mounds of discarded anything covered in moss and fallen leaves that had been dumped underneath the dead canopy.

A walk through the Vermont woods can often be revealing. It’s not uncommon to find relics from a different Vermont left to disintegrate below the trees. And in my opinion – our ruins are often one of the coolest things about the human race. We create amazing structures and accomplishments or inhabit these laborious lifestyles and let the aftereffects rot without much of a thought, leaving people like me to eagerly trace their occurrences that blur the line between litter and urban archeology. And out of any time of the year, you can be most appreciative of our habit to ruin than the fall, when visibility is best.

There was a time not that long ago, when Vermonters didn’t dig today’s Green culture. Back then, the most efficient and convenient way to get rid of anything you deemed as garbage, was to make the disposal quick and uncomplicated. This was often accomplished by dumping those items on a far corner of the farm, or let gravity take it down a river bank. Over time, these items accumulated, festering in the woods long after the farm went defunct, or their traces bleeding into our waterways or soil.

How times have changed. Today, a growing chunk of Vermonters are building a culture that feels how we coexist with our environment is a virtue, and villainize those things that don’t fall into place. And if you’re not one of those people, well, it’s also the law. But as is the trend, the movement also shakes things up, especially farmers who find it expensive and laborious to abide by new regulations, or the costs of implementing new laws or infrastructure by a government that many are losing faith in.

A lot less of Vermont is farmed now days, and much of the land has returned to forest, but these rusted and forgotten vestiges of the past still remain, now moldering in the silence of the wilderness. This particular junkyard had an eyebrow-raising amount of stuff brought there. Old tractors, snowmobiles, knob televisions, a Ford truck, religious paraphernalia, antique glass bottles, creepy childrens toys decaying in the weather, a small mound of old appliances, and so much more in depths farther down than I felt good about digging to reach. There is even rumored to be some traces of an old prohibition era still coffined back here, but there was so much to sift through, I probably wouldn’t have been able to recognize it if I was standing on it.

“I thought you’d like this, seeing how you’re into old stuff” said my friend as she went to unscrew the top from her iced tea, humorously not following me further into the collection of trash. “I figured I’d show you before I clean this all up”

“Oh, when is that happening?” I called out as I wobbled and stumbled my way over a mound of shifting garbage that squeaked and rustled underneath my crooked feet.

“Welllll…….one day.” she assured me, a tone of defeat in her voice.

Further down the road, there was the most important cog in the farm machine, the dairy barn, which excited me lots because you never know what you’ll come across in an old Vermonter’s barn. Barns are vital storage spaces, workshops and in some cases, awesomely bizarre museums.

Traditionally, a Vermont farmer would put more money and effort into keeping up the barn than anything else they owned. So much, that many of them would let their houses fall into ruin if they had to make that hard choice of where to divvy up their cash. That even goes as far as the demolition process if the construction gets too far gone. As an old timer up in the Northeast Kingdom once explained to me; “Why tear down a perfectly good barn when it’ll just fall down when it’s ready?”

According to my friend and tour guide, the old barn was close to 100 years old, filled with accumulations of its years. As a side hobby, I’m a picker when my finances allow it, and I used to love shunpiking around rural Vermont and checking out barn finds, yard sales or whatever treasures or weirdness I could spot on our backroads, so I was already wondering what I’d find inside this old barn.

The fading red structure didn’t appear to be in bad shape, or really even abandoned. If I had just passed by, I’d probably thought it was just another working farm. We pulled over in some tall grass and began to tromp our way through the threshold.

I think barns and farms play some role in lots of Vermonters lives, even if you don’t have one of your own, chances are, you know someone who does. I remember my childhood of playing in my paternal grandparents’ dusty old barns on their farm up near East Montpelier, finding ones near Chittenden County to store our 78 Toyota Landcruiser in for the winter, and spending some of the best days of my youth riding my 4 wheeler through sugarbushes and meadows on a 250 acre farm and some of the most beautiful land I’ve had the privilege of having access to in East Wallingford. Now days, I’ve been apartment jumping around the Burlington area, but man, I wish I had a barn of my own where I could set up a workshop and have a place to do projects and space to store the 4 wheeler I would most definitely buy.

While I’m on the subject – do you folks know why red happens to be the ubiquitous choice of barn attire? Simply put – red paint is cheap. But the why behind that answer actually has to do with dying stars. Pretty much; red paint is made from Iron. Iron is created when a star eventually collapses. The ground is loaded with iron, or, an iron-oxide compound called red ochre that makes a good pigment. The ground is loaded with red ochre because when stars die, they explode, and physics decrees they generate a bunch of iron as the result, which is pretty cool.

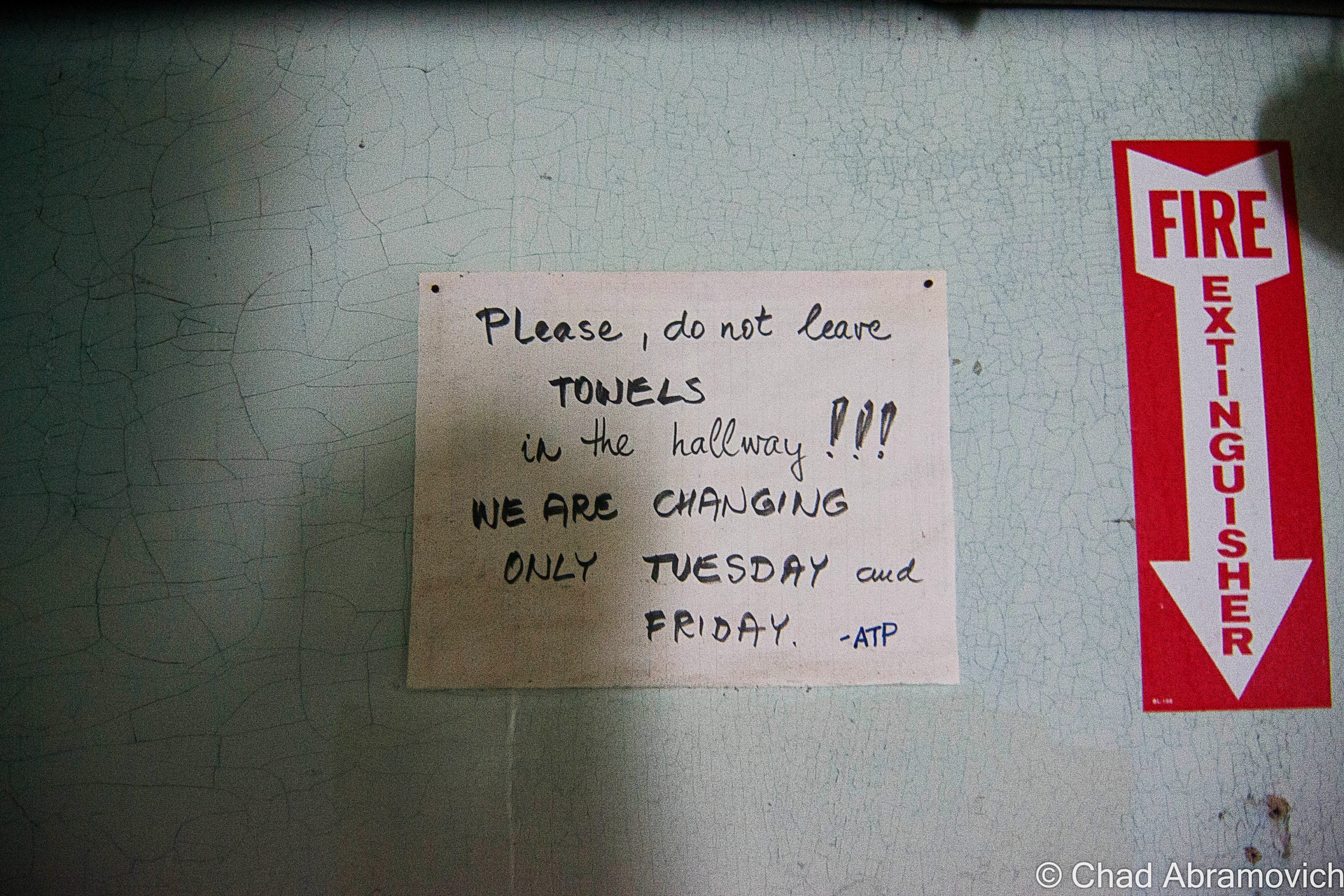

The dusty whitewashed interior of the barn was pretty cool as well. In typical Vermont tradition, the old farmhands never threw anything away, so the spaces were stuffed with antique furniture, busted farm equipment, and some unexpecteds like a collection of bowling pins. I know barns usually lived double lives thanks to Yankee ingenuity, like this great story on State 14, of an old one in tiny East Granville that formerly was the town’s dance hall that the current owners wish to restore. Maybe these guys used their barn as a makeshift bowling alley to pass the doldrums?

Walking around through hay that stuck to my boots, I realized the barn was a little worse for wear than I had thought. Structurally, it’s wooden floors and walls were beginning their slow descent into wasting away, and some of the older items stored inside were rotting to a point beyond saving.

While I was writing up this post, I remembered another old barn I had checked out many years ago, and decided to dig up the old photos. I want to say these were taken by an insecure me with my Nikon point and shoot, around the spring of 2010. I figured I’d include them in this post as well. It’s sort of funny how years ago, I thought the only way I would be any good at photography was to get myself a top-grade camera, but looking back, I think that heading out with my old point and shoot actually forced me to become more creative and observant with a limited focal distance and zoom range. Man, young Chad had so much to learn. The equipment sure helps, but it’s really the photographer behind the gadgets that makes the difference.

During that spring, I needed to get out of the house to clear my head, and one of the best ways for me to do that was to go shunpiking – one of my favorite activities still.

I found myself on some swampy backroads up in Franklin County. With the windows down and the wet Spring perfume coming through, I found myself passing by an abandoned farm, and next door, a rundown ranch house where the owning family still dwelled.

They agreed to let me skulk around their abandoned farm, but their elderly teenage son thought I was a weirdo for being interested in their place. Well, I am a weirdo, but I’ll never forget his furrowed eyebrow look and accompanying chuckle. According to him, the town actually condemned their old farmhouse when it began to violate building codes as it aged. So they moved into the ranch next door, which honestly didn’t look much better.

The best feature of the property was a tumbledown dairy barn covered in gray decay. The ramshackle structure was worth the potential threat of tetanus. The interior was filled with the debris of century old farm equipment, hidden doors and other relics. Like a beautiful antique sleigh.

I even found a century plus old book underneath some floorboards in an abandoned barn, which raised a few questions. Why was this book concealed under the floor? What else was below my boots?

I’m not into theology, but it was pretty cool. As a graphic design major, I really appreciated the headlining typography. Finding old religious paraphernalia hidden in Vermont buildings isn’t rare it seems. Around the same time, an acquaintance I knew found someone’s leather bound, ornate family bible from 1848 under his floorboards, along with a handgun and the skeleton key to his basement door, which they had never been able to access until then. The decaying book was scrawled with various notes and births/deaths of a family who used to live in his old house in Milton. The place was built in the 1840s as a hotel, and also functioned as a bar, vaudeville theater and silent movie house and an odd fellows hall, before being converted into shoddy apartments.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations throughout the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible. Seriously, even the small cost equivalent to a gas station cup of coffee would help greatly!

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4