It was the mid 1950s, and the United States and The Soviet Union were in the middle of the Cold War. The race was on, both nations stockpiling enough firepower to wipe out most major cities, vaporized in a discharge of enormous mushroom clouds. The ensuing radiation would take care of the rest. According to those in the know, if a nuclear bomb was dropped, the result would be an obliterating flash of light, brighter than a thousand suns.

Paranoia gripped the nation, and preventative measures were taken by the government. Vermont’s desolate Northeast Kingdom became one chosen location to detect and be an early warning against the end of the world.

The United States Air Force chose East Mountain, a 3,438 foot sprawling ridgeline surrounded by some of the most remote wilderness in all of Vermont, to be the site of a radar base. Construction started in 1954, and by 1956 and 21 million dollars later, the North Concord Air Force Station was functional. The base was designed to provide early warning signs and protection from nuclear fallout, as well as sending information to Strategic Air Command Bases.

About 174 men lived in the base in a village of tin and steel Quonset Huts known as the administration section, situated on a mid-mountain plateau surrounded by almost impenetrable bogs. Their job was to guard the radar ears, which resided in massive steel and tin towers on the summit of East Mountain – constantly straining to hear the first whines from Soviet bombers coming from the skies above. The giant buildings were topped with large inflatable white domes that protected the radars. The government spared no expense protecting the United States from a possible Soviet attack. People were urged to build bomb shelters in their basements, “duck and cover” drills were actually implemented in school kids’ curriculum, and almost every town had a fallout shelter (which everyone was encouraged to memorize the location of).

The Quonset village offered amenities such as a store, bowling alley and theater, barber shop and mess hall. But the wilds of Vermont were a tough place to live, especially in the winters, when snow drifts could often reach the edge of the roofs. Sometimes, the air boys would be stuck on the mountaintop when the mountain road became impassible, and would have to wait out the storm up there. Some enlisted men dreaded serving their time in Vermont because of this, but it was the city boys who hated it especially – many who served from the Chicago area. A mural of Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive once covered an entire wall of the mess hall in an effort to make the men feel more at home (but that mural can’t be anywhere near detected today). The base also provided a bus that drove to Saint Johnsbury every night, for a little stress relief and therapeutic contact with civilization, so the men could see a movie and hit the bars.

At first, there was only one way to access the base, a dirt road that traveled through tough mountain valleys and up steep slopes to the base, a 9.3 mile drive. In the winters when the snow drifts gained mass, army personnel would have to phone the base from the bottom of the mountain to let them know they were on their way up, because the road was so narrow it only offered room for one vehicle traveling one way at a time, and if you ran into someone else, well, good luck.

Later, a paved road was constructed from East Haven on the mountain’s western slope, offering another approach. Though the base was a cold functioning monument to man’s urge to destroy itself and the trembling hands of fear, it also offered a boost to the area’s economy as well as social impacts to area towns. In 1962, the base’s name was changed to the Lyndonville Air Force Base.

But the functional life of the East Mountain Radar Base was brief, as expensive costs to keep it running were adding up, and advancing technology made it obsolete before construction was even completely finished. It officially closed in 1963. Since then, its became the idol of local legends. Strange stories of death, UFOs and unknown characters skulking behind rusting ruins and evergreen forests slowly began to haunt the place.

The weirdness started before the base even closed. In 1961, a strange object – which many speculate was a UFO – was identified in the skies above East Mountain, which the military reported as lasting for around 18 minutes. A few hours later, Barney and Betty Hill were allegedly abducted by a UFO near Franconia Notch, New Hampshire, which lead some to believe there is a connection between the two coincidental events.

In 1965, Ed Sawyer of East Burke bought the property from the government for $41, 500, and what a purchase it was. The base was in pristine and authentic condition at the time, and he loved it. Sawyer made money by selling surplus equipment and scrap metal. He moved into one of the Quonset Huts and also ran a woodworking shop there. In 1969, a group of snowmobilers rode onto the property without permission. As they were traversing the lengthy access road, one of them hit a chain slung across the road as a makeshift gate, and was decapitated.

Not long after, trespassers and vandals discovered the base, and started making trips up into the vast wilds of the mountains hoping for an adventure. Sawyer installed several gates going up the roads to deter people from coming up, but he would numerously find several padlocks had been pried off and ruined. Sawyer had to replace about 35 padlocks a year. He would eventually result in shooting at trespassers to protect himself when menacing visitors became destructive and violent. He had even been threatened before.

Not only would they loot and steal everything from wiring and original furniture, but they destroyed the buildings. There was even an account where he woke up one night to a bunch of snowmobilers who were able to ride over the roof of his building because the snow drifts were so high!

The constant influx of vandalism and weather took its toll on the radar base, which has since further deteriorated and taking on a forlorn, haunting appearance underneath bounding hills and silent forests.

The property was put on the market, and remained unsold for many years, until recently when Matthew Rubin purchased it, who envisioned building a wind farm on the site, and anyone who has been on East Mountain would understand why. But after years of attempting to get permits from the state, he postponed the project indefinitely. The property has since been added to Vermont’s list of hazardous places, for massive soil contamination from oil and other motor fluids.

Around 1990, another person met their own mortality on East Mountain, when they fell from one of the radar towers and was killed. To add to the radar base’s already mysterious reputation, it’s been said that the rotting ruins have also been home to hobo camps and a hideout for the Hells’ Angels at one point.

Today, the radar base, known variously as East Haven, East Mountain, Lyndonville, and Concord, sits abandoned in a nebulous haze that hangs over the kingdom forests, the incongruous ruins littering the mountain top – the eerie silence is occasionally broken by the winds and the scraping sounds of rusted metal. A disconcerting and questionably regressive riddle to the end of one apocalyptic dream, and the uncertainty of what the future will bring.

Historical Images via The Air Defense Radar Veterans’ Association – photos from the 1960s

The East Mountain Radar Base was one of the most unique places I have ever gotten the chance to explore, and that adventure started even before we arrived there.

We approached our destination from the small town of Victory underneath the bravado of September skies and rambling mountains. Victory has one of my favorite names for a town in Vermont – it’s one of the few place names in the state that derives from an idea rather than a person or place. A suggestion for the cool name may date back to 1780, when settlers across New England were caught up in a general sentiment of Victory after the tides were beginning to turn against the British, especially after the French had decided to join the American cause.

It’s stand out name is kind of ironically fitting for it’s it’s admittedly stand out culture as a place of uninviting destitution, the power of it’s isolation is irrefutable. There are no state routes or paved roads – only unkempt dirt roads that are rutted into a landscape of hills with mangy looking forests partially scarred by ugly logging activity and expansive bogs with heavy moose traffic. The town is remote, even for Vermont’s idea of the term. It has none of the things that many towns have to formulate an identity; it has no post office, general store, gas station, school, police station, fire department or churches. Instead, a cluster of trailers in various states of upkeep huddled together at the bottom of a steep hill is the closest thing the community has to a village center, an area called “Gallup Mills”, which are what VTran’s green reflective way finding signs direct you to as opposed to Victory.

It does have a town hall though – in a restored one-room schoolhouse, which apparently sees far more feuding amongst the 62 people that live in Victory than actual productive town business affairs. I’ll take a quote from Victory resident Donna Bacchiochi in a Seven Days article that I think sums up the town; “You see how lonely it is, how out of the way it is? The reason we moved here is we aren’t social. People in Victory are like that. They don’t visit each other, they don’t kibitz, they don’t do anything like that. It’s vicious.”

In 1963, Victory made local and national news by becoming the last town in the state to get electricity, and that was pretty much owed to the by then defunct radar base being nearby. With millions spent running power up the mountains to the base, Victory took advantage of a fortuitous situation and made connections down to the valley from the existing grid.

Traveling off into the hills of Victory, we made our way up Radar Road which was built parallel to the bouldery banks of The Moose River and underneath fallen trees that hung over the road, as our tires jarred into pothole washouts. As I’m writing this, I can’t think of accurate words to describe the sense of isolation we felt up in the mountains of East Haven. Miles away from anywhere, no cell phone service, no sounds of the familiar world to ground you and give you a sense of place.

Eventually, we came across a weedy clearing in a sea of Green forest, the formidable forms of the Quonset Huts with their rusted steel facades and broken glass skulking behind the fading colors of early autumn. We had reached the former living area of the base – the sentinel forms of the radar towers high above us could be seen on a steep ridge where congested softwood forests climbed out of the swamps. Many of the huts had been razed already, leaving cement slab foundations choked with weeds. One of them was dismantled and given to the Caledonia County Snowmobile Club, where it was re-assembled. The remaining buildings were low profile, almost completely obscured by the forest that was slowly reclaiming what it once had.

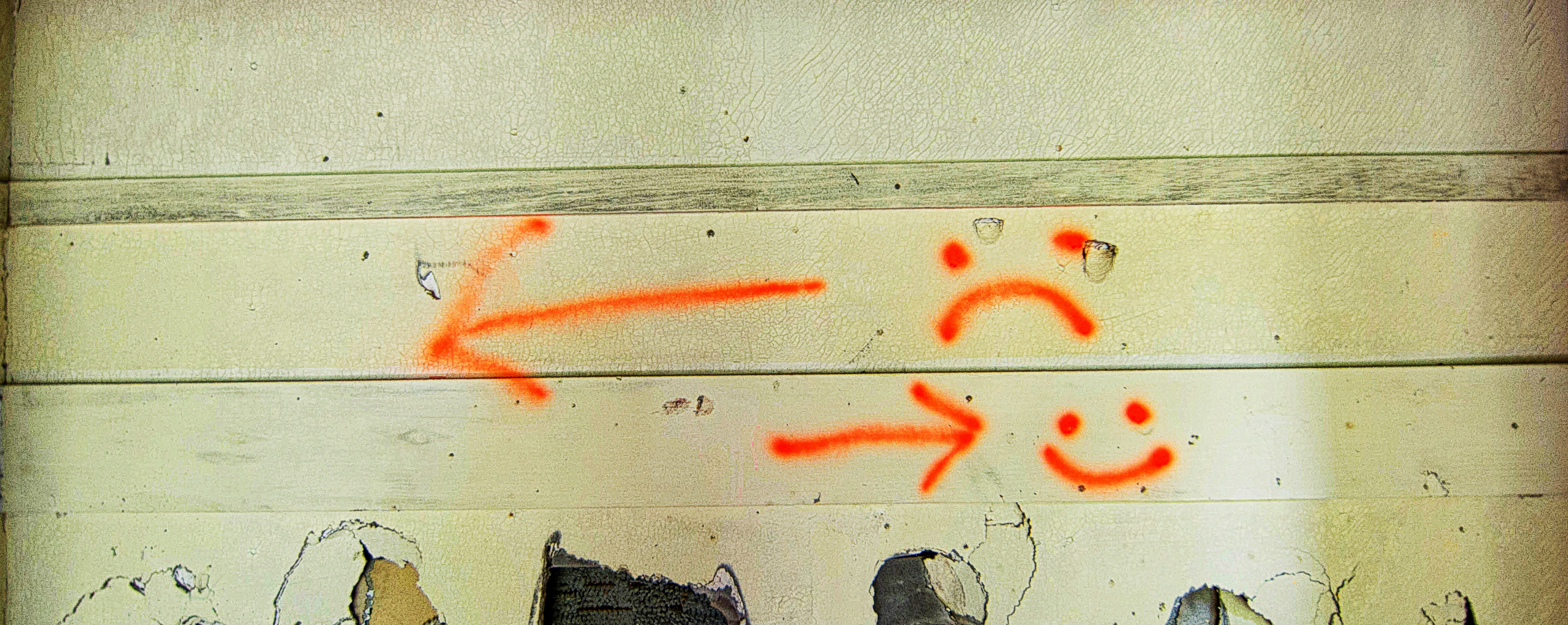

A walk through the buildings was a sentient experience over broken glass, soggy and exposed insulation, a storied compendium of generations of graffiti, and evidence of human habitation, arson and partying.

Administration Section – Fall, 2014

Return to Radar Mountain – Mothers Day Weekend 2016

On mothers day weekend, I met up with a few friends and we ventured up to radar mountain. It was 72 degrees – perfect for a road trip – and I really needed to get out of the house.

Although, a late start ensured that we got up on the mountain just an hour or so before sunset, but that didn’t stop us from having a little fun. We got a campfire going and my friend hooked up his record player to some period-accurate loud speakers, and played era-appropriate music from the 50s, when the base would have been in operation. “I only have eyes for you” was playing as I shot this, making eerie tin can sounds and tossing them across silent swamps and the silhouettes of nearby mountains – which we joked was the radar base theme song. It was an extraordinarily cool night.

The radar base was already proving to be a creepy area to explore. The compelling silence up there was occasionally met with auditory hallucinations – we would jump at the sound of what we thought were other people lurking somewhere nearby, or the oncoming roar of a motor of a passing vehicle, only to be greeted by nothing but our own fears and the self imposed things that crawled into our heads.

From the administration section, we climbed back in the car and drove up the remaining stretch of Radar Road, and were immediatly met with the most imposing road I’ve ever traveled on. The forest literally was swallowing the road – the cracked paved surface immediately pitched upwards on a grueling steep grade that kept on climbing – the growth was so thick that tree branches came in through our open windows and began to smack us in our faces, until we were forced to roll up the windows. The road was only wide “enough” for one car, and that was even far fetched. There was no place to pull over, no place to turn around. If another car was coming in the opposite direction, especially around one of the many blind hairpin turns that also happen to travel uphill, you would be screwed. One of you would have to give. At this point, the orange glow of my friend’s low fuel light illuminated on the dashboard, giving us another reminder of just how far away we were. If we ran out of gas up here, it would be a very long walk back to civilization.

But the drive to the top was exhilarating – the intoxicating scent of Spruce and Balsam trees blew in the winds and filled the car. Soon, the trees became stunted and the horizon began to open up from the dark forests, and the shapes of hazy blue mountains with their knife sharp ridge lines began to undulate in the horizon. All of the sudden, we were underneath the imposing steel skeletons of the radar towers. We had made it.

Summit Radar Towers – Fall 2014

Almost immediately, we were greeted with a good reminder at just how dangerous this place was. Several of the floors in the steel towers were rusted through, some with holes, and others with entire sections that actually swayed and bended with each passing step. Mysterious liquids of various colors rested in odorless pools on the floors and dark spaces, as the wind howled outside and rattled the walls. Rust was everywhere, and the possibility of Tetanus discomforting.

It wouldn’t be an adventure if we didn’t find a Bud Light can along the way, which seems to be the drink of choice for people who frequent these types of locations.

The best part about the visit here was no doubt the magnificent 360 panorama of the Northeast Kingdom and New Hampshire from the top of the tallest radar tower, but getting there was a game of nerves. Climbing up the already questionable structures reverberating with the groans of rusting tin moving in the wind, and up a rusted ladder coated in a layer of mysterious slime that gave you no traction. If you slipped, you plummeted several feet down towards a hard concrete floor into pools of fluids obscuring soggy insulation and rusted objects. But once on top of the tower, as you gaze into unbroken wilderness as far as you can see, and you bask in the profound silence, it’s completely worth it.

At the summit, there were visible campsites made on the slopes beneath the towers. I couldn’t help but think about how amazing it would be to camp up here in the deep, underneath the constellation light. I’m sure it would be a spectacular experience, perhaps even unsettling. As we were leaving, another car came up the road and parked, before a group of teenagers climbed out holding quite a few packs of Twisted Tea. I guess other people are taken by the strange allure of this place as well – and it draws characters of all kinds.

Proving this point, on the way back down the road, we met up with another vehicle, its roof and grill lights flashing, and it was barreling up the road. Thinking it was the police, we found a place to pull over. As the car passed us, we clearly read the words” Zombie Apocalypse Survival Vehicle” written on the sides in police-esque decals, the car soon sped out of sight as it headed towards the mountaintop.

Sometimes, the pursuit of life can bring you to some incredible places.

Update as of August 2015

A while after I had published this post, I was amused when I saw an inbox message on the blog’s Facebook page from the owner of the “Zombie Apocalypse Survival Vehicle”, which pretty much started out with the line “Hey! I’m the guy with the car!” As it turns out, he’s also one of the members of the East Mountain Preservation Group and might just be the person who is most intimate with the place. He practically lives up there, spending his free time examining it’s ruins and doing some urban archaeology to figure out how the base functioned, and the stories behind the things I saw on my trek up the mountain. So, we struck up a casual social media friendship, which transitioned into a real time friendship, which lead to us planning a radar trip together.

He picked me up in the affor-referenced Zombie Apocalypse Survival Vehicle, and we made a special trek up to the kingdom, to explore the base on the 52nd anniversary of it becoming defunct. He gave me a much more detailed tour of the place, showing me things that I had walked right by or took no notice too. One of my favorites was the collection of old cars that had been junked in a swamp that ringed the administration section. When the base was abandoned, the army trashed the place, heaping their junk and cars into the woods, and dumping lots of excess waste, such as oil and fuel tanks, into the soil. The faint acrid stench of contamination still permeates in the swamps today. Following well packed super highways made by what seem to be countless passing Moose, we were able to find the rusting remains of the vehicles. We also found an old switchboard that once controlled radar and ventilation equipment, switchboards that once served the telephones and their lead cased wires, and several old wells now contaminated with iron that stained the water a stagnant red.

But the most surprising find was what we refer to as “The Boulders”; a very literal moniker we bestowed on a man made road block just beyond the Quonset Huts. Logging equipment was used to dig a trench through the road, and then to drop four gigantic boulders into it, to prevent anyone with a vehicle from driving up the remaining two miles to the radar towers on the summit.

By far the coolest part of the trip was when we were able to get the power running in some of the buildings, after a great deal of rigging and assistance, I heard the eerie yet rewarding sound of a light that hasn’t flickered or hummed in 52 years, come to life. Not a bad way to spend an anniversary.

As it stands as I write this in 2016, the radar base and all visible surrounding property was purchased by a logging company out of Washington State. From what I was told – the company doesn’t plan on being as friendly to recreational land use as the prior landowners were. To get some tax breaks on all those acres of forest, they have to allow some, so they’re focusing on moose hunting permits. But from what I heard, all 4 gates up Radar Road will most likely be closed more than they’re open from now on, so logging and quarrying crews can do their thing without the constant interruptions of over sized trucks with out of state plates coming up the road, which surprisingly carries the traffic volume of a suburban neighborhood than a logging road in the middle of the kingdom. But, only time will tell.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my amazing fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations through out the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4