Ever since we started narrating our folklore collectively as a species, we’ve always marked the wildest places of our topography as incubators of contagion shotgun blasts for the darkest, grimmest things our human minds can create, existing in a variety of forms. These tales often like to hang around well into the intervening years where they should become obsolete, and yet, they don’t. We all deal with the dangers of the world in different ways. Sometimes, carrying on the traditions of talking about these kind of fabled places is a way of dealing with these dangers. And sometimes, these monsters reveal the most about humanity.

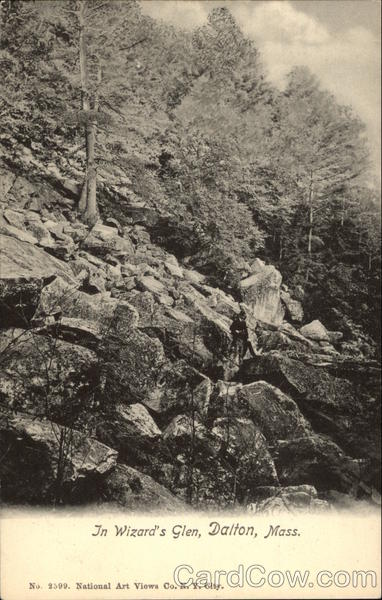

Wizard’s Glen in the Berkshires is a wild, picturesque depression between two steep-sided hills. Intersected by a lone, narrow and often washed out dirt road with it’s to-the-point name of Gulf Road, you are welcomed into this attention-grabbing area by tons of boulders that are stacked up the hillsides, some covered with some impressive and patriotic graffitic murals instead of the flippant teenage rabble I expected to find in such an area.

The name “Gulf” interested me before I even began to think about Wizard’s Glen. The noun is a distinctive part of the obscure Vermont vernacular. Gulfs are known to the rest of the world as a large area of the sea or ocean that’s almost entirely surrounded by land, expect for its mouth. A Vermont gulf is a landlocked one – found in our mountains. We know them as deep ravines (or more dramatically, an “abyss”) that run between two parallel mountains or rises. To my knowledge, us Vermonters were/are the only ones to use the word in that sense. Vermont actually goes as far as to erect road signs to let travelers know that you’re passing through one. Granville, Proctorsville and Williamstown Gulfs come to mind, all of which are great drives. But finding a gulf outside of Vermont, even only in the form of a street name, was sort of cool to me. There is also a Gulf Road in New Hampshire near Brattleboro.

This particular Gulf Road runs east to west over the bumps that are the Berkshires. Both entry points are unobtrusive and start out as an unremarkable suburban street with storm drains, crumbling curbs and cobra head street light fixtures that run to the very point when suddenly, the pavement ends, and the obsessively trimmed lawns cease to exist, and you’re in a surprisingly sizable wilderness area that runs for about 1.8 miles between Lanesborough and Dalton. But at the slow speeds you are forced to crawl on this winding roadway, it feels much longer.

Wizard’s Glen

The area known as Wizard’s Glen, vs. the rest of the area that’s not known as Wizard’s Glen, co-exist very inconspicuously with each other. If it wasn’t for the wayfinding graffiti marked boulders, I would have driven right by it.

I got out of the car and noticed the temperature was a pleasant few degrees cooler, and the forest was soluble underneath a still silence. I immediately began to get interactive with my environment and started clambering on top of the boulders and under Hemlock boughs and inside the caves and crevices of undetermined pasts.

Godfrey Greylock described the diminutive gorge in 1879 as being “as though and angry Jove had here thrown down some impious wall of Heaven-defying Titans. Block lies heaped upon block; squared and bedeviled, as if by more than mortal art…”

I have to say, the stories about this place were far more waggish than it’s real life locality would suggest, which only intrigued me more. This place has spawned plenty of strange tales of the supernatural and the dreadful, and many of them are almost as old as New England is.

Someone had told me that the hollow is known for its strange sounds and echo-related properties, and claimed that if you banged on one of the rocks with a hammer, it would make a noise sounding like you were smashing the keys of a xylophone, while inexplicably, the surrounding boulders wouldn’t. However, that enticing theory was disappointingly proven false. Well, at least it didn’t work for me.

It was here that Indian priests and shaman centuries ago performed rituals, ceremonies and incantations amongst the rocks in the ravine known for its echoes. Because they revered this area to have special properties, it was said they even offered human sacrifices here to Hobomocko, the spirit of evil. There is a flat, broad square-ish rock known as “Devils’ Alter” where these cryptic sacrifices were said to be imposed. The rock today has faint traces of red stains on it, which some say is the remaining blood from the aforementioned occurrences – but the reality is the stains just come from iron in the rocks. The unique name Wizard’s Glen was actually derived from these legends. And it makes sense – it’s aesthetically the type of place where strange happenings can’t be easily dismissed.

The best known story of the glen is of John Chamberlain, a hunter from Dalton about two hundred years ago whose whopper of a story was passed on in Godfrey Greylock’s book Taghconic: The Romance and Beauty of The Hills in 1852, when he interviewed Joseph Edward Adams, a ninety-year-old man who had heard it from the hunter eyewitness himself.

Chamberlain had killed a deer and was carrying it home on his shoulders, when he was overtaken in the hills by a storm. The tired man decided to take shelter in a cavernous recess in Wizard’s Glen. But despite his fatigue, he was unable to sleep and wound up laying awake, lying on the earth with his wide open in the dark. He was suddenly amazed when, according to him, he saw the woods bend apart, disclosing a long aisle that was mysteriously lighted and contained “hundreds of capering forms”. As his eyes grew accustomed to the new faint light, he made out tails and cloven feet on the dancing figures. One very tall form had wings, who the hunter thought to be the devil himself.

As Chamberlain lay watching the through the spiteful deluge from his cave shelter, a tall and painted Indian leaped on Devil’s Alter, fresh scalps dangling around his body and his eyes blazing with fierce require. He muttered a brief incantation and summoned the shadows around him. They came with torches that burned blue, and began to move around the rock singing some sort of harsh chant, until a sign was given, and a nude Indian girl, shrieking, and fighting, was dragged and flung viciously onto the rock.

The figures now rushed towards her brandishing sharpened weapons in their outstretched arms, and the terrified girl let out a shrill cry that the hunter said haunted him for the rest of his life. The “wizard”, (who I’m assuming is the prominent figure with the wings), raised an ax, as the rest of the group waited apprehensively for the oncoming carnalish blood bath. Lightning flashed and quickly illuminated the dark pocket of woods, and Chamberlain noticed the the girl’s face quickly fell on his. The look she gave him tore at his heartstrings. He gathered as much courage as he could, and decided to act. Grabbing his bible he traveled with, he ran towards the debauchery in self-righteous fashion, clutching it in front of him and hollering the name of his god. There was a crash of thunder. The light faded, the demons vanished and the hunter was left sopping wet in the middle of the woods in silence. When morning came, he had almost convinced himself that it was all a dream, until he realized his deer had vanished.

Though not much is really known about Chamberlain, it was apparently well documented at the time that he was “no lover of the Indian race,” which may explain more about the content or the intent of this fanciful legend than anything. In my humble opinion, this eyebrow furrowing story probably shouldn’t be taken as verbatim of a real event. Even as mythology or folklore, it lacks essentially what most of these tales are built on; meaning.

There is no good evidence that any Native American group up in our part of the country even conducted human sacrifices, but I do believe that Wizard’s Glen held some sort of ritualistic importance to the area’s original natives.

Hobbomocco is a real Algonquin deity, though, and was more so associated with darkness and the night. His name is related to all Algonquin words for death and the dead, and has no relation to the Christian idea of Satan, unless misinterpreted by, well, a Christian. In the Algonquin viewpoint, Hobbomocco is actually a side or nuance of the natural world, a potential source of dangerous visions and power, which can be obtained through communication, sort of similar to Voodoo deities, and how it’s said that with enough persuasion, you can persuade them to either carry out good or evil intentions. I think the rather dramatic story of Wizard’s Glen may be more of a manifestation of the friction between two clashing cultures and their ideas, where everything else is sort of devalued, open for interpretation, or simply cast away.

There is also said to be a talus “cave” known cryptically as Lucky Seven Cave somewhere in the glen. However, after some time clambering around and almost rolling my ankle, I couldn’t find any opening that could shelter a human who wasn’t a small child, so either it’s long toppled, or I just didn’t have good directions. Some speak of covens, convergences and rituals still being practiced in the cave and around the site, given the various paraphernalia and shitty beer cans that you can find there. I find it interesting that this site may still be attracting modern day wizards, witches or spiritualists, or people that think they are these things, but when I visited, I had the beautiful place all to myself under the heat of the day, despite the fact that it’s a geocache location and the famous Appalachian Scenic Trail crosses Gulf Road near the glen, just east of there.

More Wild Places

While I’m on the topic of gulfs, I’d highly recommend checking out what may be Vermont’s most beautiful; Granville Gulf, a rugged and impressive wilderness area of moss laden cliffs, ferns and waterfalls.

If you’re curious about more of our regional wild places with extraordinary folklore attached to them, my blog entry on Glastenbury and the popularly dubbed “Bennington Triangle” may be worth a read. It’s certainly one of my favorite Vermont tales to tell.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations throughout the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible. Seriously, even the small cost equivalent to a gas station cup of coffee would help greatly!

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4