Queen Connie

Vermont’s roads are pretty regulated, so there isn’t much here in terms of weird or kitschy personalized properties that people like to put into the broad category of roadside Americana – which includes a perpetually growing compilation of the same genre (nonstandardized) but vary widely in sentiment and imagery.

But, that doesn’t mean obscurities can’t be found along Vermont’s byways. Take the tiny farm town of Leicester, whose most famous denizen can be seen lumbering over the small oval-shaped lawn of Pioneer Auto Sales, right along the side of Route 7 either before or after you approach the tiny village center – which is pretty much an intersection with a few houses and a newly reopened gas station that now has a growler filling station.

“Queen Connie”, which it’s sometimes referred as when it’s not called “that big gorilla holding the VW bug”, is a huge 20-ft. tall, 16 ton, concrete ape, holding up a progressively rotting Volkswagon Beetle in one of her upraised arms, while the other arm is stretched out, palm upward, acting as a place where someone could grab an uncomfortable seat and a gimmicky photo opportunity.

But how did something like Queen Connie end up in aesthetic conscious Vermont? And what’s the story behind it? Actually, the answer is pretty straight forward – according to what I was told anyways. The owner of the car dealership had commissioned local artist T.J. Neil to do some concrete work around his pool at home. He was impressed with Neil’s work, and casually suggested another project; to do something cool to spruce up his business. Neil surprised him by suggesting a hyperbolized gorilla – his only reason was because he wanted to see it holding up a car. In 1987, Queen Connie was constructed using steel reinforced concrete, and she’s been observing activity on Route 7 with a disgruntled facial expression ever since, and for Vermonters who are into the weird, might be one of their first forays into oddity hunting.

Though I’m glad Vermont isn’t carelessly overdeveloped like other states, emblems like this are a pejorative thing to build here in the present tense, so it makes it all the more enjoyable.

Up The Molly Stark Trail

I was heading down to explore parts of southern Vermont with a friend. My summer turned into a lot of stress and setbacks, and I felt like my life was becoming as standard as my white apartment walls. My prescription was a long drive, and the lure of autumn’s sway just makes road trips better. Passing through my favorite town of Wallingford always cures a frown on my face, and as we got farther south and the trees began to turn gold in the hills around Mount Tabor and Dorset, I enthusiastically recalled a defunct marble quarry I hiked to last summer.

Route 7 turns into a limited access highway through most of Bennington County, until it reverts back to full access in Bennington and brings you right into its historic downtown district, the center of town being where it intersects with state route 9. I took a quick jaunt up the hill to the Old Bennington neighborhood to take a few photos of one of my favorite buildings in Vermont, The Walloomsac Inn, then ventured up route 9 eastwards into the mountains.

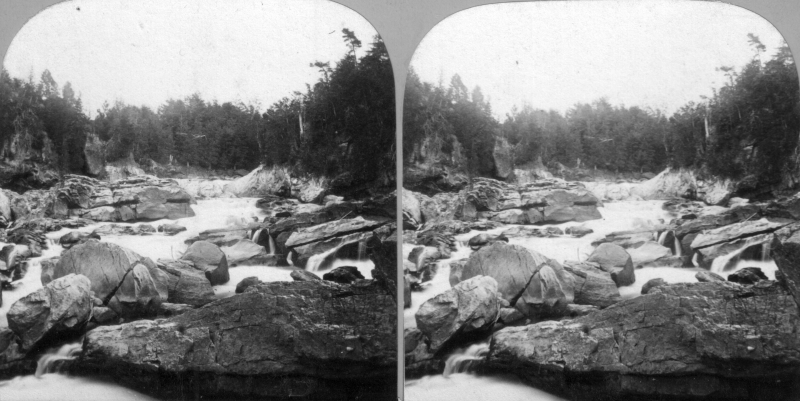

Route 9, also known as The Molly Stark Trail or The Molly Stark Byway as the state issued scenic byway signs tell you – is one of my favorite drives in Vermont, and the same sentiment could probably be said for quite a few other people. It’s an extraordinary road to gawk at through the windshield of your car, and even better when you’re stopping to get out and look around. The mountain road twists and turns through the innards of the national forest and gains elevation and grade pretty much as soon as you get beyond Bennington’s limits as it starts to climb the first of many hills and parallels the boulder filled Walloomsac River. To be honest, lots of things on this road vie for your attention.

A sense of awe and anticipation builds in me when I see a trademark brown and white national forest sign, telling drivers that there are various access spaces to Vermont’s Green Mountain National Forest for the next 15 miles or so. That includes the massive Glastenbury wilderness, one of Vermont’s largest undeveloped areas, but more known for the titular defunct town and about 2 centuries worth of weirdness that culminated on its many slopes and took off like a contagion shotgun blast into paranormal sensationalism. But it”s hard not to be fascinated by the large expanse of wilderness. The huge area holds ghost towns, a slew of trails and forest roads, man-made feats of engineering, and plenty of mysteries. Just ask the Geocaching community.

We passed through forested Woodford, the highest town in elevation in Vermont at around 2,215 feet, then descended into Wilmington. Which is where I unintentionally found some local curio. A green 1915 iron truss bridge first caught my eye, because it was obviously abandoned, as indicated by all the trees growing through it. The underwhelming replacement was a simple concrete and steel span that bridged the river inches away. As I was gazing at the bridge, I noticed a strange white sign across the bridge that was put up on a small weedy embankment that welcomed me to “Medburyville”, and gave me a precise census of 31 people and 26 pets who I guess lived somewhere nearby in the rural area.

I was at a loss here. The area around the sign was pretty much an undeveloped light wilderness area, and I knew that we had already crossed the Woodford/Wilmington town line. I’m a pundit on Vermont geography and had never heard of Medburyville before, so I was pretty curious. What was/is Medburyville? A local parody or some kind of irony? A name of an obscure back road Wilmington neighborhood?

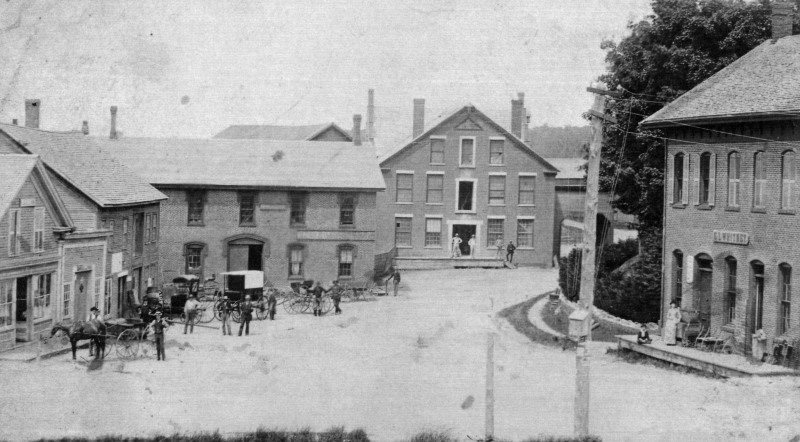

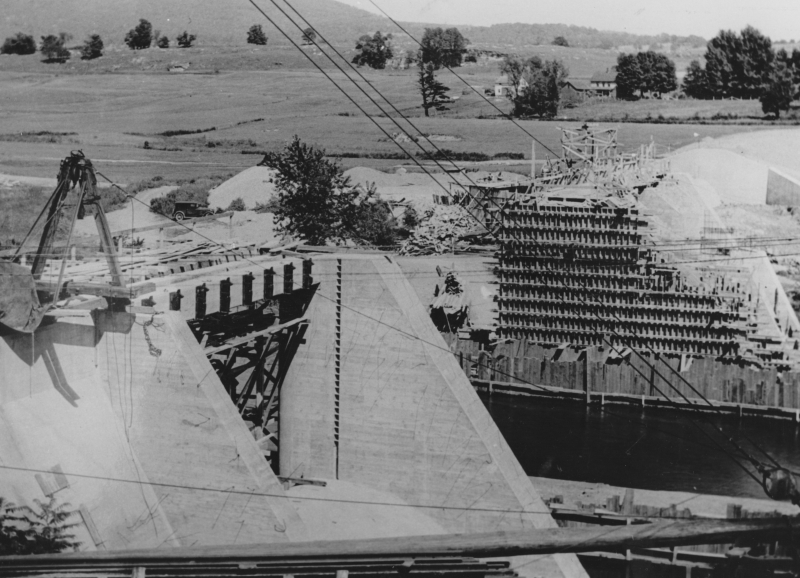

I was curious if there was a mystery or story here, so I sent an email to the Wilmington Historical Society. In their reply, Julie Moore explained that Medburyville was a village in Wilmington, but was erased when the Harriman Reservoir was constructed for the purpose of flood control. There was a mill, several houses and a railroad line that ran through the area at one point.

Today there is only a small aluminum sign that raises more questions than answers. Just a few feet from what was/is the Medburyville area is a narrow arm of the aforementioned reservoir, which is experiencing pretty low water levels lately so it was more sandbars than water when I drove by. Local lore has it that when the reservoir is low, a slimy church steeple from the former village is exposed, but I didn’t see anything that day that looked out of place in a reservoir.

Another obscure footnote is that there once was a placename along the reservoir that had the post office address of “Surge Tank” – a name of a temporary settlement that sheltered the men who built the Harriman Reservoir dam that had it’s own recognized post office. The post office also moved around between Readsboro and Whittingham – depending on wherever construction was happening. I still see Surge Tank sometimes on obscure place name lists. Like Medburyville, Surge Tank is long gone, and without a sign to commemorate it.

Back on the road, the forests occasionally break up a little and you got a positioning glimpse that you were right in the middle of the green mountain chain. Unlike some parts of Vermont where a high elevation isn’t surrounded by other mountains and instead reduces off into valleys, the mountains around Wilmington and Marlboro stretched as far as the vistas, with various 440 million-year eroded summits slanting into other rounded domes. A few “runaway truck ramps” with large yellow signs and rhythmic blinking lights were a reminder that the undulating byway had the potential to be more dangerous than scenic for other drivers, and judging by the scars and pit marks in one of them, it had been used recently.

The “100-Mile View”

But it was the so-called “100-mile view” in Marlboro that was the most impressive. I’m not sure if that name is superlative or not, but I suppose it doesn’t really matter because the view is awesome. From a large wooden deck with coin functioning viewing apparatuses for the tourist crowd, you can see what’s left of southern Vermont before it transitions into the Berkshire Hills, and the bumps of southern New Hampshire, including Mount Monadnock.

One of the ramshackle old lodging cabins from a deceased ski resort, which I was about to hike to, sits on the edge of a drop off below the overlook, and might be one of the most photographed site among the sights. I took a walk down, and there was a laminated sign taped to the twisting floorboards telling people like myself to keep out – it’s not actively maintained (as evident by the peeling paint) and can be dangerous if the building decides to tumble down the hill. But I was able to get a shot through a dusty old window along the side and gaze curiously at a few items of older furniture left inside.

I live in Vermont’s largest city, and dig the scene there, but sometimes my hometown is just too oversaturated with people for my taste. I really ache for having access to land like I did when I was younger, where I could go 4 wheeling and hiking and just let out the things storming in my mind. So my predilection was that I could sit on that porch all day or night and gaze off into the distance in my own reverie, listening to Gregory Alan Isakov albums.

The cluster of tourist buildings that sort of delineate the maximum height of land between Bennington and Brattleboro were all once a part of Hogback Mountain, a defunct ski area cut out of the slopes of Mount Olga which has mostly been recovered by nature.

Hiking Around Hogback Mountain

Hogback was one of the longest lasting family owned traditional ski resorts in the state, and arguably is one of the best lost ski areas in Vermont to explore, though you’d probably guess either of these things while driving by the few diminutive red buildings sitting in tangled underbrush along a slight rise above the wide shoulder of route 9. You’d probably never guess the property was even a ski hill unless you were able to catch the white lettering affixed to the former first aid building that reads “Hog ark Ski Area”, which in all honestly would be a memorable name for a functioning ski hill.

I decided to walk down from the overlook and have a look around at the property. Good thing I wore jeans – the land was wild with tangled undergrowth, and most likely, ticks. Having been bitten by one a month ago, I didn’t want to go through that debacle again. A few old buildings, the rusted bones of an old lift line and a squint-to-make-out overgrown ski trail could still be traced.

Vermont is the land of skiing (and snowboarding) and our pioneering ski hills ranged from extremely plain rope tow affairs to more detailed mom and pop establishments.

If you’re a New Englander, I’d say we’re pretty lucky to have a great site like the New England Lost Ski Area Project. Between that and the book Lost Ski Areas of Southern Vermont by Jeremy K. Davis, I got a startling impression of how many ski areas we once had just in the lower part of Vermont, and how many of them have been, well, lost.

Hogback Mountain itself seemed to be something special. The ski area warranted a pretty long chapter in Davis’s book and a long entry on NELSAP – considering other areas had merely a few sentences. It has a lot of history, so much I had to condense it a bit for the sake of keeping people reading this blog post.

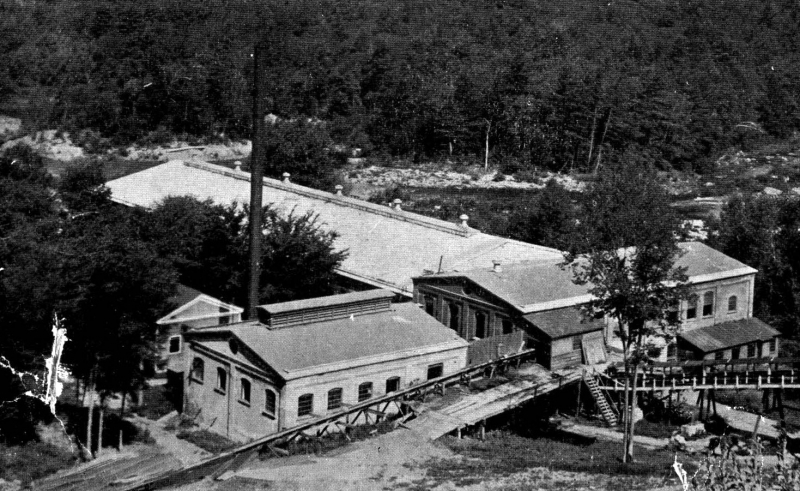

The truth seemed to be that Hogback was envisioned by a community of people who loved skiing, and the consequences were real. Hogback opened for the 1946-47 ski season on prime real estate owned by Harold White, and was operated by the Hogback Mountain Ski Lift Company out of Brattleboro, as well as several of the families who owned the various businesses along route 9, like the White’s who owned the gift shop, the rental shop, the Marlboro Inn and other rental properties. The Douglass’s who were involved with the ski shop, and the Hamelton’s who were involved with the skyline restaurant.

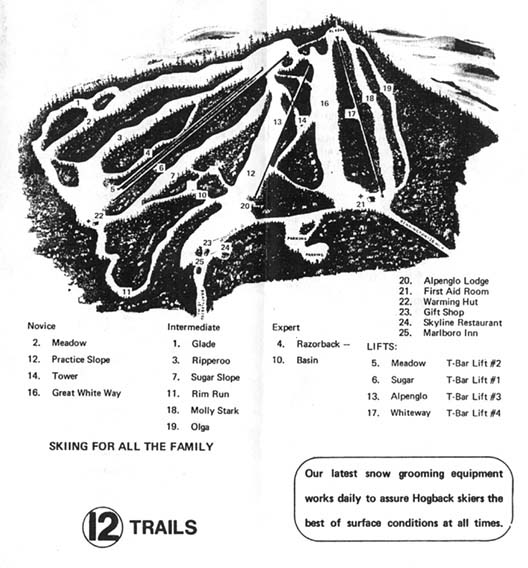

It featured a Constam T-Bar which could move 900 skiers an hour and was the highest capacity lift in the country at the time. Old brochures and trail maps promote the ski hill’s location in Vermont’s “snow belt”, a high annual snowfall area of the Green Mountains which at the time, received an average of 120 inches. The Vermont winters of today are a bit more disparate.

Hogback’s highest elevation was about 2,400 feet (the base area being at around 1,900), which helped preserve the natural snowfall much better than lower area ski hills, which made it so beloved. I observed some older trail maps, and discovered that Hogback had a unique layout. You’d begin your day along route 9 where a hotel, gift shop and Skyline Restaurant were, and ride a rope tow to the practice slope, but intermediate or expert level skiers would have to transport over to a different face of the mountain to access the main T-Bar and more advanced trails.

Over the years, the laid back ski hill caught enough popularity from a top notch ski school, excellent snowfall and a gorgeous mountain where skiers would admire spruce trees crusted in snow. In the 50s, it started to expand, and would continue that momentum through the 70s. More trails were cut down the slopes and made easier accessible by a Pomalift and the addition of 4 more Doppelmayr T-bars. There was also a Quonset Hut brought to the property that served as a ski-in snack hut.

Seriously, this place was a big deal. A lot of the history or accounts I read about the mountain was that plenty of southern Vermont kids learned to ski here. It also helped develop a local interest in ski races and became home to the Southern Vermont Racing Team. If a nearby community, like Brattleboro, had an outing club, they probably went to Hogback. The mountain developed a pretty enthusiastically devoted fanbase. The ski school changed instructors a few times over the decades, each new presence contributing to it in their own way.

But towards the 1980s, snowfall began to change to a lack of snowfall. Between not enough natural snow to ski on, rising costs of operation and increasing competition from bigger resorts that were becoming more common on the scene in Vermont mountains, the small mom and pop ski hill eventually couldn’t compete. Hogback’s story is similar to most of Vermont’s lost ski areas. Not being able to compete or stay consistent, most of them became fading ghosts.

Abandoned ski hills are interesting real estate. What do you do with them? Some have subsumed away in the caprices of nature and others re-opened or became private operations. In Hogback’s case, the Vermont Land Trust and a group of adamant people worked pretty tirelessly over the years to secure the funds to purchase and secure the land to save it from becoming a condominium development with a marketed quintessential nature-esque type of name. The purchased acreage was then transferred over to the town of Marlboro, and the cool Hogback Mountain Conservation Area was the result. It’s now glorious protected land, with an abandoned ski hill in the middle that Vermonters can enjoy.

Some of the old ski trails are still maintained and pruned, so hikers, snowshoers and cross-country skiers can still enjoy them. Though, for me anyways, I found that finding those trails was a bit of a challenge.

To my delight and surprise combination, if you bushwhack through some waist-high tangle weeds and growth, you can still find some of the old ski trails, which were still hikable! Well, it’s subjective I guess, but I thought it was achievable. Using the linear rusted cables of the former chairlift as wayfinding points, I decided a short early autumn hike was a good idea. The trail oddly cleared out the farther up I climbed, until both the trail and the lift sort of ended in a blissful and fragrant silence. I was a little bummed I didn’t find an old chairlift or more paraphernalia. If I had gone up farther, I would have eventually stumbled upon the Mount Olga fire tower, which I’m told had splendid far reaching views. You can get there far easier than scrambling up Hogback Mountain, by hiking over via Molly Stark State Park.

My list of places to visit in Vermont alone is so long, it’s hard to cross stuff off of. I’ll get up there one day.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations through out the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible. Seriously, even the small cost equivalent to a gas station cup of coffee would help greatly! Especially now, as my camera is in need of repairs and I can’t afford the bill, which is distressing me greatly.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4