I woke up at 5 AM, was reminded that I wasn’t a morning person, and stumbled out my back door at 6. My friend was waiting for me in his parked car as the headlights cast a dull amber pallor onto quiet streets that were under the cold gray dawn. It was 41 degrees and I was all shiver bones in the new coming chill.

I stopped for a few gas station coffees and was rewarded with my early rise by wicked fog that obscured the landscape off route 7 in a glorious visceral veil that turned everything into mutated shadows. I caught some of it on my cell phone hanging around Dorset Peak, before it burned off.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BKwcFvFg9gG/?taken-by=the_tyranny_of_influence&hl=en

The weather lately has been prime for adventuring, and I’ve been aching to get out. This trip would give me that spark in my brains I was looking for. Feeding off my desire to visit as many obscure places as I can, I figured that two ghost towns in southern Vermont would be a great way to spend my day. These vanished places are probably some of the most obscure in the state. But everyone pays the price to feed, and I arrived back home exhausted and practically limping, so I suppose that can be gauged as one hell of an adventure. But I’m also someone who’d willingly drive 8 hours just to find an oddity, so a follow-up day of sluggish exhaustion was easily worth it for me.

Somerset

I’m willing to assume that plenty of Vermonters haven’t heard of Somerset. If you take a gander at a state atlas, it’s a narrow rectangle at the western edge of Windham County that nudges into eastern Bennington County – giving the latter county its block lettered “C” shape.

The entire burg is filled by the Green Mountain National Forest. It has a year-round population of 2 people and is only accessible by a forest service road that is all too easy to miss because of its small, squint-to-read street sign. But out of the two destinations I was planning on scouting, Somerset was the only one that was somewhat accessible by vehicle, so we started out with that one. I was still sipping my coffee which was getting unsatisfyingly cold, trying to shake off a road trip thematic Tom Waits song beating around in my head.

Somerset Road sort of plunges immediately down an embankment right off The Molly Stark Byway in woodsy Searsburg, and almost as quickly, turns to washboarded gravel after passing a few houses with scores of signs telling you that they’re not into people trespassing on their land. The increasingly destitute road now follows the Deerfield River and is thick with trees. We noticed that some older power lines had still been strung up along the road, and ran the length of the Searsburg portion. But it was evident these lines were archaic predecessors of modern day utility infrastructure. Some of the poles were leaning pretty horizontally as we got further down the road, and that’s when we noticed that they had glass insulators still on their lower rungs, now defunct as the power company had long clipped those wires and modernized things a bit a few feet higher up. Glass insulators were developed in the 1850s originally for telegraph wires, but were later utilized for initiative telephone wires and electric power lines, until the 1960s when they began to be phased out and simultaneously became a feature of interest.

I thought it was pretty cool to see them, and that there are still more or less untouched Vermont back roads that still exist. Older relics like these are becoming increasingly hard to find nowadays. And, apparently, there is a collectors market, clubs and even shows dedicated to them. Anything can have fanfare it seems.

As soon as we hit the Somerset town line, which was marked by an omnipresently strange country icon of a bullet-perforated speed limit sign and an abrupt transition of bad gravel road to worse gravel road. The power lines stopped, and for the next several miles, we were deep in the type of woods where you really couldn’t see the forest through the trees, and they were all in the throes of their glorious descent into their perennial death.

There are really no places in Vermont like Somerset. Though there are 2 census documented year-round denizens, the amount of people gets to about 24-ish during the summer months – they’re all people who have camps there. In a 2011 interview done by WCAX, one of two Somersetians, Don Gero, explained that people don’t stick around here. Both residents are bachelors, and he quipped that because Somerset has no electricity or phones, women don’t want to live there. “They can’t use their hair dryers or wash their clothes” he said. He’s also not happy about the summer camping population, who are “two dozen too many” for his tastes, and paeaned for the good ol’ days when I guess none of them were there. Often, the current culture of these odd places is more interesting than the past events that created them.

Charted by Benning Wentworth back when Vermont wasn’t Vermont and its land was quarreled over by New York and New Hampshire, the New Hampshire governor and businessman (in no particular order) just drew a whole bunch of lines on a map and granted towns without knowing anything of the area’s geography. The most important thing was that New York couldn’t get their hands on any of the land, so he didn’t concern himself with pesky things like that. Vermonters decided they preferred anarchy, and would later orgonize an independent republic in 1777 with our own currency and postal service, and then, the 14th state in 1791 when we tried on our current name.

Somerset is all mountains, far away from anything and hard to get to. Despite that it wasn’t great real estate to early settlers, 321 people tried to live here in the town’s 1880s apex. Logging was the only way to make a few bucks, so they deforested all of the area mountains. They attempted to have log drives down the Deerfield River, except for when it was low, which it was, a lot.

The demand for timber was ravenous, and that convinced a railroad line to lay tracks up to the mills, which were a huge boon to the town, but also helped speed up its death. A town depending on a finite resource comes and goes like fads always do, and most of the trees in the area were hacked down, the inevitable consequence was that both the logging industry and the town became a literal washout.

The town’s last hurrah was when the Deerfield River valley was eyed for a future facing wonder like hydropower and the cash it could bring. In 1911, the Somerset Dam began to take form. The dam was built by massive work crews of about 100 men in shifts, doing everything by hand and took about 3 years to complete. The reservoir did what reservoirs do best and collected the desired water, which submerged what was left of town and the railroad and the mills.

At some point, there was an airfield in Somerset, which has also vanished. Today it’s a free and minimal amenitied national forest campground under the same name. According to campers who post reviews online, it’s either wonderfully remote or a place where amateur outdoors folk or “Massholes” go to belt loud music and litter. Given my experience at campgrounds, I’d say it’s probably both.

I also found out, which isn’t detrimental to your life if you don’t know, that you can take class D forest roads from Somerset all the way north to the Kelly Stand Road – a west-east oriented forest road that’s also one of Southern Vermont’s most scenic. If you enjoy shunpiking, finding more of these back road byways to explore is usually not a bad thing.

Glastenbury

Vermont author Joseph Citro introduced Connecticut’s faded hamlet of Duddleytown (which was really only a place name in the town of Cornwall named after the trio of brothers who bought land there) as “the granddaddy of all New England window areas” in his book Passing Strange, which to me made a pretty good lead-in to that chapter (it was actually the last sentence in his chapter on Glastenbury). I’d like to term swipe that to introduce Glastenbury on a more localized level, as the granddaddy of Vermont’s lost areas, for multifarious justifications.

Getting to the ill-fated town is nothing short of a challenge today, and was for the people who tried to make a life for themselves up there over a century ago. It’s isolation, stubbornly built up in an area of 12 peaks over 3,000 feet with no convenient access, makes it one of the most unique places in the Green Mountain State, then and now.

If you’ve been following my blog, you might know that I’ve been very interested in Glastenbury since I was a kid, and wrote about it extensively, my long winded self trying to pack as much detail as I could into a blog post. This entry expands on that.

To summarize things; the vanished town of Glastenbury was charted in 1761, and reflected the circumstances of its neighbor Somerset when it was naively plotted over some of the worst topography in the state. As a consequence, it wasn’t really until the 1850s when anyone paid interest to the town, when people figured out they had an entire mountain of wood to deforest for profit, and a logging/charcoal duality became Glastenbury’s only industry.

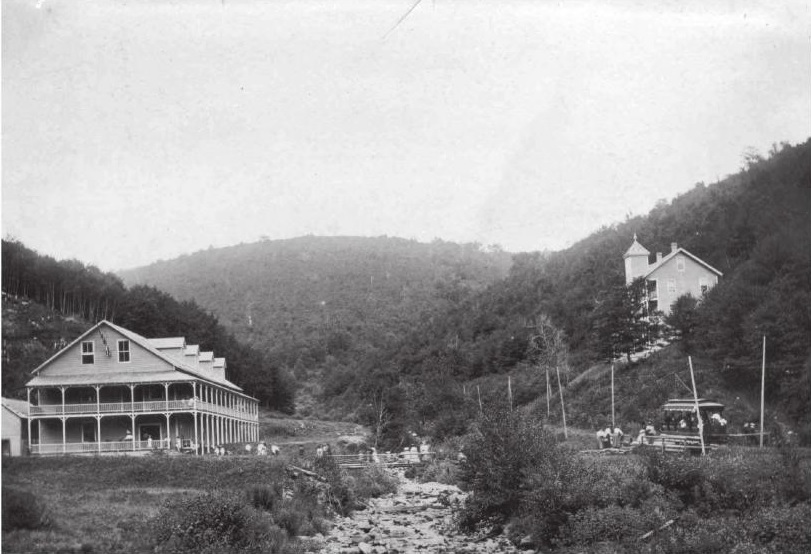

About 12 brick kilns for charcoal production were built in southern Glastenbury at an area known as “the forks”, because it was a distinguishable location where Bolles Brook split in two in a V-shaped parting of ways. A small and rough, lawless village designated as South Glastenbury grew up around these kilns, including a one-room schoolhouse, loggers boardinghouse and company store.

The steepest railroad ever built in the U.S. was developed to get up into South Glastenbury. The electric trolly line was the only element that made the town a pragmatic place; bringing down money making lumber and charcoal, and later, bringing up tourists. Many have no idea that aforementioned rail bed still exists, and if you follow it, will bring you deep into indistinguishable wilderness to the grave of the old town. Our adventure started well before we got out of the car when we navigated our way to the portal into the forest.

Funny enough, Glastenbury is still technically a town, at least in the haze of Vermont law. A gaze at a state atlas, or a Google map search, will show you a dotted lined square that represents a town boundary, only, there is nothing within the square. It’s considered an unincorporated town – or, one of 5 Vermont communities with a population so low, that instead of a town government handling its affairs, those things are managed by a county or the state. Or the national forest service I guess. There are a few people who still do live in Glastenbury – populated by just 6 people ( their properties are pretty much clustered near the borders of either Shaftsbury or Woodford), who also have achieved somewhat of a level of intrigue beyond the strange phenomena that describes the town.

I’m going to stay quiet on the access road we took, because it’s pretty evident that the people who have their addresses there don’t want the crowds. (Like the folks in Somerset, they live in the boonies for a reason, only, these folks express their discontent via threatening scrawl) When we drove up the gravel roadway, we immediately began to pass some shabby looking properties, all of them with handwritten and somewhat threatening signs warning nonlocals not to park their cars there, or else.

Fearing our car would be cannibalized for its wheels in an uncomfortable back woods “we warned you!” sort of situation, we decided to find what we designated as the safest parking space on the road, far away from any discernable houses and no parking signs. Hoping that we didn’t make a stupid mistake, we trekked up the road on foot, found the forest road, and began our hike into one of the most fabled places in state mythology.

We hushed our sound as we heard another one that was all too familiar to me. We heard an approaching 4 wheeler. Because of my suspicious nature and not knowing what sort of people were this deep up in the woods, I decided to relocate myself as far to the side of the trail as I could, give a friendly nod and let them pass. As they got closer, I saw it was a younger couple, a man and a woman, and they slowed down as they saw us. I decided to take the mutual encounter and get past my social anxiety and spark up a conversation with them.

Actually, I wanted directions, because we were beginning to second guess ourselves as to where we were, and if we could find any of the ruins, and I really didn’t want to leave disappointed.

The front handbrakes were pulled and their 4 wheeler slowed down to a stop. The gentleman, who was wearing a camo baseball cap and sunglasses smiled at us and wished us a good afternoon, his wife sat behind him silently observing us with a friendly expression. I returned the greeting and asked him if he could direct us to South Glastenbury.

“Oh, the forks?” he asked. That casual nickname drop meant that they were aware of it, and I nodded my head, my excitement immediately betrayed my casual expression I was trying to keep. I also thought it was pretty rad that locals today still use the place’s old handle.

“Yes, the forks. Are we close? Would it even be traceable in all this?” I gestured to the thick woods around me to make a point. “Well, yeah you can find it. But this is sort of the wrong time of year to be looking for that sort of stuff. Also, it’s bear season up here you know. Uhh, how’d you guys know about Glastenbury, just curious?” he asked us with a backdrop set to his tone.

I wasn’t quite sure if my candor had triggered a nerve, or how to give him a cropped statement of how Glastenbury found itself sticking to the flypaper of New England mythology, but I had a feeling he already knew that. “So, you know about Middie Rivers?” his wife spoke up. “Yeah, I do” I stated. There was no need to be superfluous there. But for those of you who are unfamiliar with Glastenbury and it’s monsters;

Local lore includes a froth of big hairy monsters, a cursed Indian stone that swallows humans, UFOs, mysterious lights, sounds and odors detected by colonial settlers, and numerous hikers walking off the face of the earth here between 1945 to 1950 – earning it the nickname; “The Bennington Triangle” in 1992, which has adhered itself to the flypaper of popular culture.

Fortean researchers like John A. Keel conjured up the term “Window Area”, which I had referenced at the beginning of this section, as a place where some sort of interdimensional trapdoor can be found. Well, that’s one theory anyways. New England is loaded with so-called “Window Areas”. Cryptozoologist and researcher Loren Coleman identified Massachusetts’ “Bridgewater Triangle”, using the term “triangle” to designate any odd geographical area. Joseph Citro followed up by coining “The Bennington Triangle” – both are said to be “window areas” It’s also one of my favorite terms to use when talking about this caliber of local weirdness.

Who knows where the flickers of truth are in all this. And that’s what makes everything so damn fascinating, because there is truth in these tales tall and true.

It’s also the mountain’s paranormal and controversial tales that attract modern day professed ghost hunting clubs and social media sensationalists, whose meddling are an affront to both locals and reasonable judgment, which really seemed to have damned the wilderness area.

Don’t get me wrong, these haunting stories are partially why I found myself hiking up the mountain, because of how impressionable they were and still are to me, but I find that there is also a line between being a civilized researcher, and becoming one of the monsters you’re chasing and exploiting it on a tawdry clickbait website with a headline that reads something like “{insert subject} will give you NIGHTMARES!”

Middie Rivers

The elderly Middie Rivers was the first of a handful of people who reputedly disappeared in the mountains in or near Glastenbury. Anyone who tells the story of southern Vermont’s Shangri-La recants that Rivers was an experienced woodsman who, while leading other hunters on the mountain, got a bit ahead on the trail, and was never seen again.

“None of that is true”, his wife said declaredly. “Rivers wasn’t a hunter or an experienced woodsman at all! He was actually from Massachusetts, and he had borrowed a rifle from his brother-in-law, who he was hunting with. He’d probably never even hunted before, and certainly never guided other hunters up here. The only thing that’s true about that story, is that he did disappear.”

“One theory is that he might have fallen down an old well. That seems pretty plausible to me”, I added. She nodded her head. “Yup, that’s what we think too. I mean, there are plenty of them up in the hills. But vanishing without a trace…people love to say that, because it backs up the mystic or, I don’t know, the ghostly impression about this place. They’d rather believe that than the facts, because it’s more interesting” she furrowed her brows and cut herself off in annoyed contemplation – like she knew what she wanted to say but couldn’t get it out. I was loving this conversation. “I know a bit about Middie Rivers” she continued after a moment. “I know a lot of stories and legends, passed down by relations to him. The Loziers – that’s the family who is related to him – we knew/know them, they passed down all sorts of stuff to us growing up. They have a camp up in Glastenbury still, like us. I even have a picture of Middie Rivers”.

“Ah, that explains the 4 wheeler then. I was a little surprised to see you folks! I assumed this was just a hiking trail or forest road”.

“Yup, we’re one of two camps in Glastenbury on this trail. My wife’s father built it years ago. We were grandfathered in. After the national forest took over, no one else was allowed to build up here or drive up this trail anymore. As it is, we need a special permit to have 4 wheelers so we can ride up here” – the husband cut in. “Did you see all of the gates?” I nodded in confirmation. We had to crawl underneath a few of them just to advance our hike. He continued; “We used to have friends up all the time, they used to come up in huge parties on ATVs up the trail. Now you can’t do that. It’s ridiculous, but hell, we’re not going to fucking lug all of our shit up to the camp on foot” – he then gestured to a cooler on the back rack of his 4 wheeler to emphasize his point. I got it. My friend and I had been walking for over an hour now, and I was already exhausted. “Our camps have been here for a long time – they started out as plywood cabins with dirt floors, and over the years as they were passed down, we’ve improved them a bit. No one else can build up here now.”

“I mean, it’s really probable that Middie could have fallen down a sink hole”, his wife interjected herself back into the already broadening conversation. “Sinkholes?” I asked, hoping I delivered a cue to get any sort of further information. “Ayuh, it happens more often than you think. Sinkholes swallow hunters all the time! There’s tons of them up here. People have hunted this mountain all their lives and still report getting turned around in the woods and intimidated here.”

“Because of the cross winds that meet on Glastenbury Mountain?” I prodded, a showing a little pride in my research. She nodded her head.

“I’d love to hear more about Middie Rivers, or any stories you guys have, if you’d be interested in chatting? I can give you my email or something?” I attempted. I couldn’t help it, I live for stuff like this. There is just something underneath my skin, a desire to make sense of everything. I’m definitely the type to overload myself with information.

At this point, his wife broke out in a lopsided grin and told me that she wasn’t interested in speaking any further about Glastenbury, without actually telling me she didn’t want to speak anymore about Glastenbury. “Well, we’ll be on our way now” said her husband, his thumb pushing the ignition and the engine promptly firing up. He gave us directions that were incredibly vague, but given the lack of wayfinding points, were the best he could do with people who’ve never been in those woods before. I thanked the both of them, tipped my hat in gesture, and both groups parted our opposite ways down the trail.

The Forks

It didn’t take long before we were unclear of the given directions and insecure about how much we remembered. It didn’t help that there were plenty of brook forks along the trail, tripping my thoughts up to think that any of them could be the forks.

As we continued our trek up the trail, we sighted something that sort of sketched us out. I’m laughing to myself as I type this sentence, but it was a cozy looking, nicely upkept log cabin which was probably one of the camps the baseball capped guy was talking about. There was an open lawn area out front that was mindfully mowed and solar panels on the roof, with an outhouse in back. It’s hard to explain what it is about off grid living, or seeing a home way out in the boonies, that sends odd reactions that crawl up your spine. I suppose that so many of us are just accustomed to being hooked up to utility poles (in some more repressive states, it’s actually against the law to be off the grid), that this sort of makes us subconsciously weary, like there is something “weird” about the arrangement, and easy to stereotype the people that chose to live like that and how they’re of their own sort. But then I remember that I’d live like that too if I could.

But still, I picked up my pace a bit, wanting to get out of sight of the cabin and back into the woods. Then, we ran into another fellow on a 4 wheeler. This time, our approaching character was an older gentleman. We side-stepped off the trail again, nodded our heads, and went through the same rounds of introductions as last time.

“The forks, huh? Well, I mean….you can’t make out much of the old hotel foundation anymore, but it’s right off this trail. Nothing much left of the kilns. Might be some iron bands, maybe bricks.” Then he pointed to an offshoot 4 wheeler trail that ran through an area thick with prickers and berry bushes. “There’s more kilns up that knoll there” he said, his wisdom rolled confidently off his tongue wrapped up in his heavy Vermont accent. “Oh, uh, that trail looks like it goes behind the camp we just passed,” I said uncomfortably. Though my hobby of exploration often involves trespassing, I wasn’t about to skulk around someone’s land up in those hills, especially inhabited land. People in the boondocks have guns. “They aren’t home are they?!” He said, a little wonderment in his inotation.

“No, we didn’t see anyone when we walked by”, I returned, grinning at his unexpected humorous reaction.

“Oh, good!” he said, his enthusiasm almost made me crack up. I wondered if they got along or not. “But yeah – there’s more of em’ down that trail. Well, I’ve never seen them, but I know they’re there!” This time, I didn’t contain my mirth. I liked this guy. I asked him to clarify our misdirections a bit, and he gave us some of the most Vermont directions I’ve ever gotten – far superior to the ones I got when searching for some of our state’s mysterious stone chambers.

“Well, when you get to the forks, take a right instead of the left crossing over the brook, then go up the mountain a ways but still make sure to parallel the river – look down and you’ll eventually see the kilns. Or what’s left of ’em anyways. ” Just then, a Glastenbury traffic jam formed behind the old timer on his 4 wheeler, as three teenage rednecks on dirtbikes pulled up and sort of just looked at my friend and I stoically, the last one in line revved his engine impatiently while refusing to make eye contact and tried to flaunt his, I don’t know, machismo? Or maybe he was just impatient. I shook his hand and wished him a good afternoon, and we were on our way.

More walking down the trail later, and we approached a very standout fork in Bolles Brook and the rail bed portion of the trail we were on ended and transitioned into a slender path beyond a wooden bridge that crossed the brook. We had found the forks.

Visiting the peaceful and secluded location of Glastenbury town was a strange experience. Knowing the lore and the history there sort of make you look at this otherwise banal stream crossing in the woods through a different set of lenses, ones that makes professed monsters a bit more discernable. Unless there is just something in Bolles Brook that made/makes the locals morbidly imaginative.

On our way down the mountain, we saw a couple fellas standing barefoot in the chilly waters of the brook smoking pot – a scent that followed us halfway through the rest of our hike. One gave us a toothless smile and a wave, and kept on giggling at whatever it was they were talking about. I won’t deny that they picked a nice afternoon for woodsy shenanigans.

Thankfully, our car was as we left it when we got back, and we sluggishly made our way back down to Bennington to grab a burger.

My friend and fellow explorer Josh is into video editing and decided to film our oddysey. Cinematography is something I keep saying I’m going to get into more, but my laziness and reserved nature always seem to prevent that from getting a checkmark on my list. If videos are your thing, and you want to see my friend and this blogger being sort of goofy/awkward while tromping through the woods, I’ll link you below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jnQWzRuiTCo&app=desktop

Things worth mentioning:

If any of you are interested further in Glastenbury, I’d highly recommend author Tyler Resch’s venerable book about the history of the town. I have a copy of it in my library.

I’d also like to suggest Joseph Citro’s Passing Strange, a detailed compendium of New England folklore and weirdness. It was one of the first books I bought as a kid, and my worn out copy is still with me. Both of these books helped further my research and curiosity.

If you missed it, here is my first post on Glastenbury, if you want more on the town’s history and ghastliness.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations throughout the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible. Seriously, even the small cost equivalent to a gas station cup of coffee would help greatly! Especially now, as my camera is in need of repairs and I can’t afford the bill, which is distressing me greatly.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4