For years, I’ve been interested in Vermont’s unique political divisions; gores, grants, and ‘disorganized’ towns – just some of the things I’ve discovered thanks to being a map nerd! I found it fascinating that there were delineated areas on the map that had little, to nothing in them.

On a firey September day that felt more like July, me and my friend set out on an ODDysey towards Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, the state’s wildest and poorest corner where some of these enigmatic areas are clustered. I’ve always loved the kingdom. From my dad pulling me out of school as a kid to go fly fishing on the legendary Willoughby River in Orleans, to hustling up at Northern Vermont University in Lyndonville when I was older, I have fond memories of the NEK, and always kinda associate it with The Monkees – because whenever I used to head up that way with my mom, we’d always listen to them on CD in her car, so I totally had them in my head on the ride up.

I wanted to see one place in particular; Lewis, one of Vermont’s five “disorganized towns” (a phrase that has always amused me) – which refers to towns with populations so low, or sometimes never luring any people at all, that their charters were revoked.

It felt fitting that we were heading up to the deserted realm north of Island Pond, a rough and tumble railroad village in the town of Brighton that’s the hub of that piece of the NEK, so much so that most wayfinding signs point you to Island Pond instead of Brighton.

Island Pond has always had a sort of an eccentric reputation, and I think a lot of that has to do with the temperament of how isolated the place is. Seclusion can be a lightning rod for weirdos, outlaws, religious cults, and the preternatural.

One of my favorite Island Pond tales of intrigue involves a carpenter renovating an old farmhouse outside the village in the 1980s. Across the road was an old farmer’s pasture that had long been overgrown and disused, so imagine how startled the carpenter was when he happened to glance out the window and see a young girl herding a flock of sheep in a field that was formerly empty seconds ago. When he confusingly went to investigate, the sheep and the girl had vanished. So he got back to work, until a few minutes later when he looked out the window and saw the girl and the sheep again, only this time, the girl was waving at him. He apparently quit the job on the spot!

UFO sightings nearby at an amazing abandoned radar base, and quite a few “Bigfoot” (or some variation of a wild and wily creature) sightings have also been handed down and proclaimed through all the big woods that edge town. Who knows what other morbid or macabre things that are still skeletons in Island Ponders’ closets… (and you’re a local, feel free to send me an email and tell me!)

Island Pond got its name from the 600-acre pond with a 22-acre island in the middle of it, which lead the Abenaki to name the area Menanbawk, which literally means Island Pond. Whites decided to keep the name but use the English translation.

The pond of Island Pond has probably existed since the last glaciers grinded on through the area, but the village of Island Pond got its start in the 1850s, when the Grand Trunk Railway, the first international railway that linked Montreal to the port of Portland, Maine, laid their tracks through the kingdom, which was very much a sort of last frontier in Vermont at that time. What would become Island Pond village just happened to be the halfway point, which made it a big deal – a total of 13 tracks once merged downtown. The railroad turned into memory by the 1950s, and the town depends on outdoor tourism nowadays – it’s pretty much the snowmobile capital of Vermont – but architectural elements of its former rowdy railroad days are everywhere. Island Pond is a strangely beautiful and unique part of the state that’s very much worth a trek up towards.

Stopping at a gas station at the water’s edge to grab some suspicious sandwiches, we were on our way!

You Can’t Get There From Here

As that vintage Vermont vernacular goes, you can’t get there from here – and because of Vermont’s rural and inconvenient geography, that’s often somewhat the case, so we’re not really pulling your leg or anything.

Usually, it’s a now stereotypical expression of Vermont identity that means you actually can get there from here, but the “there” is usually remote, and it requires a very long-winded, confusing route, no doubt complicated because of the very mountains that give our state its name, and whether the road is plowed or not in the winter. And that’s further complicated by mountainous parts of the state that are dead zones for GPSs and cellular service.

Lewis, Vermont

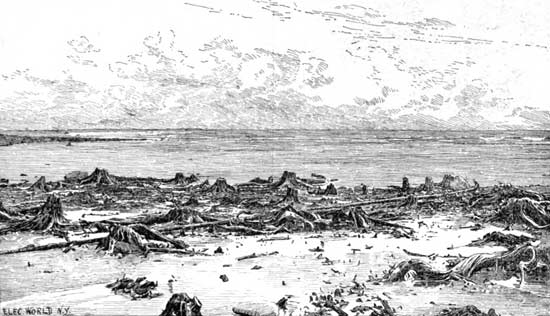

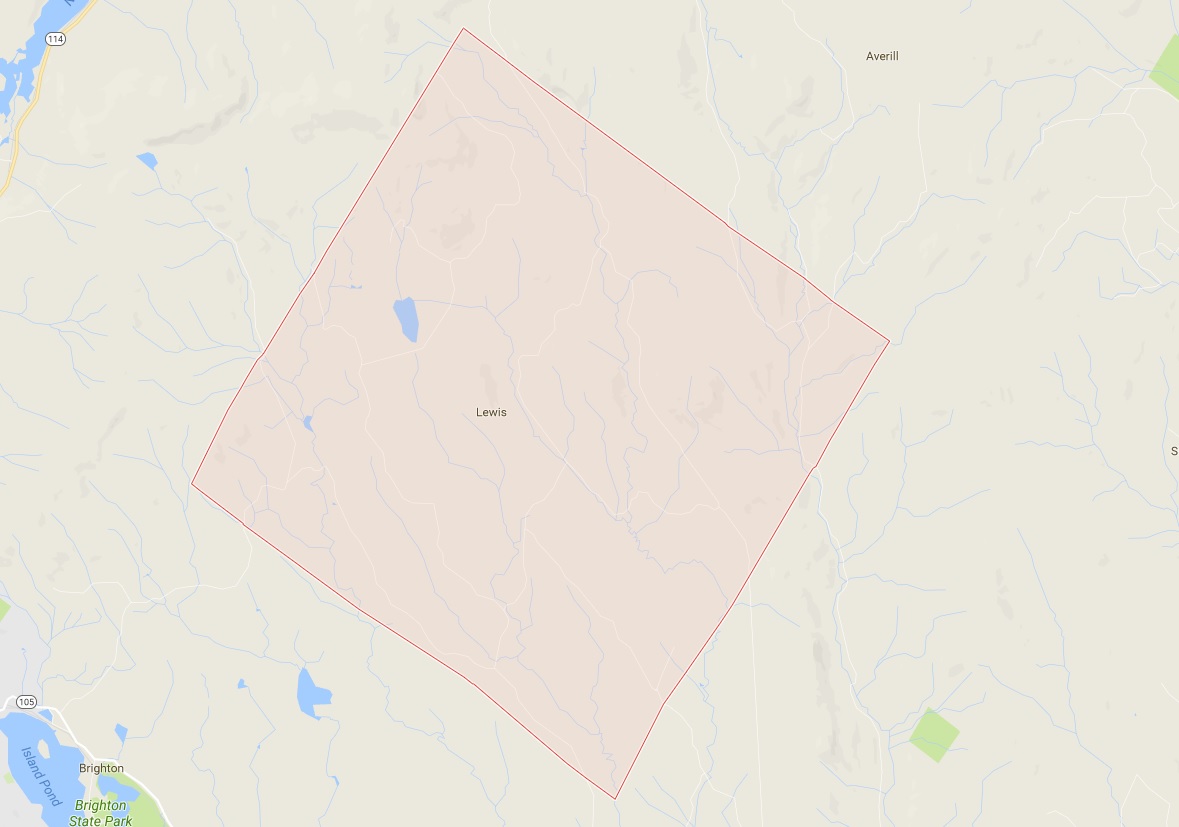

Lewis, Vermont has a population of zero. Charted early in 1762, it was heavily timbered, rough, and mountainous. It never attracted a single settler, so no roads, villages, or post office was ever established. The northern half of town is made up of mountains all in the 2,000-foot range, and all but one are unnamed. The southern half of town levels out into mostly semi-swamp known as Yellow Bogs, and they’re filled with mangy-looking forests that stretch out as far as you can see, which kinda backs up the ugly name.

Though Lewis is void of permanently inhabiting humans – loggers, hunters, and sugaring operations have all taken advantage of its space. At one point, most of the land within Lewis was owned by the Champion International paper company, until they sold off their 132,000 acres – most of which the state of Vermont eagerly acquired with the intention of preserving. As a result, most of the flora and fauna in Lewis is pretty young. But! Lewis – and the Northeast Kingdom – is at the southern edge of the largest biome on earth: the boreal forest! Named for Boreas, the Greek god of the Northwind, the boreal forest encircles the entire northern hemisphere in a band that stretches across Alaska, Canada, Scandinavia, and Russia – the boreal forest accounts for nearly one-third of all earth’s forests! Pretty cool, right?

Lewis is also considered one of the “holy grails” of the 251 club, a cool local social club that challenges interested participants to visit all 251 of Vermont’s towns, cities, unincorporated areas, and gores. Some folks make it more fun by customizing their adventure – like making points to visit every library, post office, state park, or another Vermont icon – the general store. There’s even a film dedicated to it! It’s one of my Vermonty ‘bucket list’ items, along with eventually being able to make my own maple syrup. I even became introduced to this great Instagram account recently, where the Instagrammer plans on taking a photo in all 251 burgs. It’s also inspiring me to stop being such a procrastinator.

Lewis is hard to find. There are no state routes, ‘welcome to’ signs, green VTrans wayfinding signs, or any indications that the place actually exists. Using an atlas as a guide, we headed northeast of Island Pond and took a few class D logging roads, which are the only roads in Lewis, up into the area marked by that indicating yellow dotted line that showed we were, in fact, in a town.

According to the map, we should have been able to get there via Lewis Pond Road, but when we turned off where the unsigned road should have been, we were met with what was just a 4 wheeler trail, and a gate, and a gravel dune that would have wrecked my friend’s car. I guess you really can’t get there from here. So we had to do a little scouting for another access point, which we found further east down Route 105 and was little more than a passable but thin forest service road.

The rough road marred with gravel banks took us deep into thick wilderness occasionally punctured by a few awesome ramshackle hunting camps that had been standing for multiple generations (which I regret not taking some photos of!) – skirted around Lewis Pond, and eventually brought us up the slopes of Gore Mountain – one of the few topographical place names in Lewis – to a cleared section of mountainside where we enjoyed a terrific view of the NEK and out towards the hazy blue bumps of New Hampshire’s White Mountains, and we had the area all to ourselves.

We found an accommodating boulder to sit on, enjoyed some gas station sandwiches, and just enjoyed the silence and the view and a world that was big and full of autumn. I remember the foliage that day being just ridiculous. I had no idea the views up in Lewis were gonna be so fantastic! It was definitely an evening I’ll remember.

The other named feature in Lewis is to-the-point named Lewis Pond, which is only 7 feet deep, undeveloped, apparently has some good fishing, and as beautiful as it is silent. We spent a while just lounging around the shoreline as the water lapped calmly at the cedars.

I’m not sure why the fact that the wobbly diamond-shaped town only has two toponyms is a bit surreal, but psychologically, it is. It feels like everything else within the 39 square miles that’s considered Lewis is a sort of an uncanny terra nullius, and speaks to our control freak side of human nature to label and categorize things, to prove that something exists, to achieve just a bit more of a grip on this world.

I’m fascinated with human psychology, and how a lot of the time (but not every time), things we consider as ‘odd’ are because we make them odd, because they don’t jive with our architected ideals and social rules. The only thing truly odd to me is the fact that we blindly subscribe to so many of these rigidly particular doctrines without questioning them.

But, I’m wicked into this stuff, and I guess I’d be both out of a blog and identity if I go too deep down that rabbit hole.

Today, the Nulhegan Basin Division of the Silvio O Conte Wildlife Refuge – whose goal is to try and protect the waterways that feed the Connecticut River – occupies a huge chunk of Lewis, and is named after the Nulhegan River, which basically translates to “deadfall trap” – a savvy snare that’s usually a log that’s used to capture small game by falling on it – and is a connecting title to the Nulhegan Abenaki People who were the first inhabitants of this domain.

Though the Nulhegan Basin was formed by a pool of magma solidifying here 300 million years ago and subsequently eroding away – which developed the current scenery, it’s apparently one of the coldest places in all of the northeast, with an average of 100 inches of snowfall a year and around 100 frost-free days.

There are other ‘disorganized’ towns in Vermont, but Lewis is one the most exotic to check out because of its rawness. Because people like speaking in superlatives – my personal pick for ‘most’ captivating of them would be the next-door-neighbor ghost towns of Glastenbury and Somerset down in Bennington County if anyone was wondering.

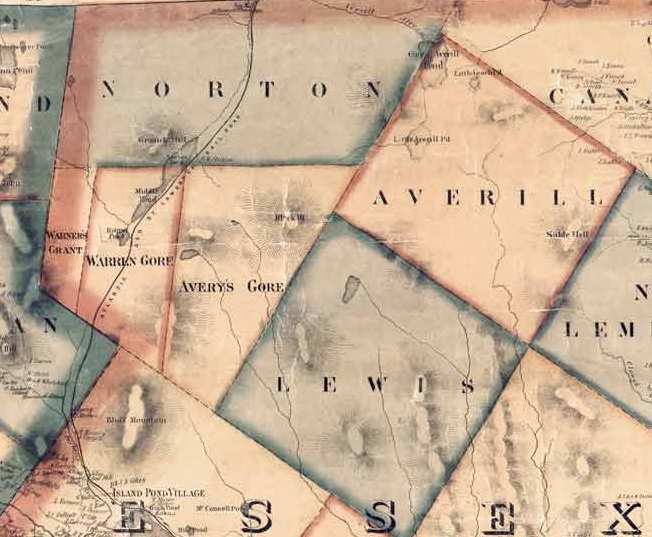

The other three out of five disorganized Vermont towns (Averill: pop. 24, and Ferdinand: pop. 32, and of course, Lewis) are all up in remote Essex County and all border with Lewis, basically making a huge chunk of the northeastern corner of the state pretty capacious, and making them eligible for a mention in this blog post. And standing shoulder to shoulder with those three towns are three of Vermont’s other geographical curiosities, two out of our three gores (the third being Buel’s Gore which forms Chittenden County’s dagger-like southern tip and consists of the dramatic Appalachian Gap), and the state’s only grant! All this chaos by simply drawing lines on a map.

And speaking off – just “down the road” from Lewis exists another state geopolitical oddity that I just had to quickly jaunt towards before heading back home; Warren Gore.

Gores and Grants

What’s a gore? It sounds gruesome, but it’s not, even though my spellcheck is really fighting me on my use of the word.

Scottish immigrant James Whitelaw would become Vermont’s official surveyor in 1787, replacing the often error-proned Ira Allen and becoming considered as one of the best map makers and surveyors in New England. But in Ira’s defense – inaugural survey work is hard.

Survey Crews would embark into unmapped wilderness to do just that. Using a 66-foot chain and wooden posts, they’d attempt to delineate new town boundaries, and then camp out for the night.

But there were still pieces left over; awkwardly sized areas never charted to any town, or given to early land grantees as disappointing compensation for basically getting screwed out of land they were promised.

In a land where possession is about 3/4th of the law; the end result became known as gores, and Vermont once had 60 of them! Currently, we’re down to just three – the rest were eventually absorbed into their neighboring towns to make the map a little less confusing, which makes gores some of the rarest creatures in the green mountain state, and pretty much non-existent elsewhere in the country apart from northern New England, which I think sorta lends them their air of charm.

Gores are often triangular, but sometimes not, as in the case of Averys Gore, which is more trapezoidal, and Warren Gore, which is rectangular. It’s their triangular shape, though, that gave these parcels their curious name. Gore is an old English term that referred to the shape of a spearhead, which is what early cartographers thought they resembled.

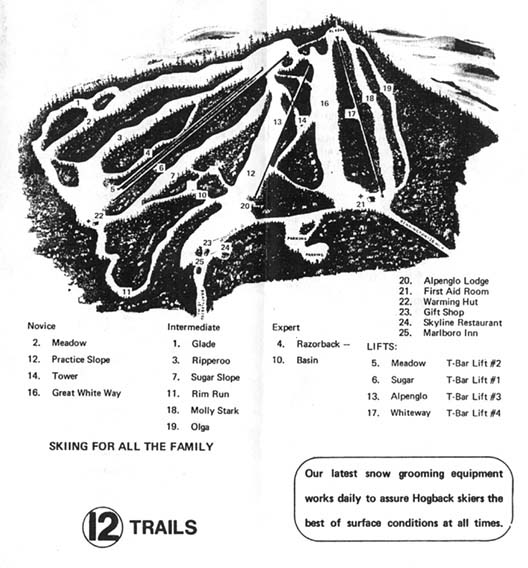

Warren Gore is tandem with the Mad River Valley town of Warren. Warren was trying to get a charter in 1780, but couldn’t because it lacked the total amount of decided acreage needed to create a town – which the Vermont legislature said had to be 23,000 acres. So the grantees scrambled to find the remaining 6,595 acres of land, which they did, just completely disconnected, all the way up in the Northeast Kingdom. Technically, they had what they needed, and in 1789, Warren was charted in two pieces (also known as a “flying grant”) – the smaller part becoming Warren Gore. But the two places never had anything to do with each other.

While Warren lured settlement and skiing, Warren Gore, sometimes called “Warren’s Gore”, went the static route of most gores, and attracted only 10 people by 2000, and lost 6 of them by 2010.

The desolate State Route 114 runs pretty much through the center of the gore, and is mostly bookended by deep woods and the pretty shoreline of Norton Pond. Apparently, old guidebooks used to call it “the roller-coaster road” due to miles of continuous sharp rises and dips that made you sorta feel like you were riding a roller coaster. Well, I was absolutely down with that experience, but I guess I didn’t notice anything that was too different from a bunch of other roads in Vermont, so maybe the road had been leveled down over the decades.

I took a tour through the gore and turned around in tiny Norton, an old lumber town of around 169 people that has reverted back to forests and small hill farms. Norton is a 45th parallel town ( the latitudinal line that’s half the distance between the equator and the north pole), and until pretty recently, had one of the last remaining “line houses” in Vermont – or a building built right on the American/Canadian border which is now absolutely illegal to do, in part of northern Vermont being uncooperative during prohibition. The most famous one is undoubtedly The Haskell Library and Opera House in the unusual village of Derby Line, where the stage is in Quebec and the seats are in Vermont. In Norton’s case, it was a general store that was split in two by the border, until it was demolished in 2021 and is now a grassy lot.

Inbetween Warren Gore and Lewis is Avery’s Gore – Vermont’s largest gore – a large trapezoidal wedge of land void of people or infrastructure. The only way in is on aptly named Gore Road, which is just a really nice logging road that dead-ends in the middle of the gore, near one of the only points of interest, an undeveloped pond a bit ironically named Unknown Pond.

West of Warren Gore is tiny Warner’s Grant, Vermont’s only grant, which is exotically considered to be the most inaccessible land tract in Vermont, and its existence is because of the sad plea of a troubled post-revolutionary war widow.

Hester Warner was the widow of revolutionary war hero Seth Warner (who Vermont state route 30 is named for). Warner was cousins with Vermont’s patron saint; Ethan Allen. With The Green Mountain Boys, Warner would lead the capture of the British fort at New York’s Crown Point while Allen was commandeering Fort Ticonderoga in May of 1775.

The Continental Congress was pretty impressed with that scheming lot and declared them an official militia. Warner was so well venerated that he was voted captain over Ethan Allen! But the war would eventually wreck him, and he’d retire and retreat to Connecticut in 1780, dying there a few years later at 41. His poor widow, Hester, literally and in idiom, was now burdened with the problem of having 3 children to raise but barely having the means to do so. So she despairingly reached out to the legislature. Her husband did so much for the revolution, surely they would give her some assistance.

They did wind up coming through for her, just slowly, and ironically, not in a way that would actually help the widow Warner.

Their compensation came in the form of 2,000 acres in the Northeast Kingdom of practically inaccessible highlands that was coarsely timbered, which they named Warner’s Grant.

Beyond that, history seems to have lost track of Hester Warner. Records do show that she never lived on the land. It seems that like the widow Warner, nobody else wanted to give living there a shot either. Warner’s Grant remains today as it was then, empty – apart from some logging activity.

I’d like to someday get up into Avery’s Gore and Warner’s Grant, but last time I was up that way, it was getting late. Too late to drive into the deep woods on logging traces – so those two are still on my list.

All of the places I’ve mentioned in this post are managed by a special state department – The Unified Towns & Gores of Essex County, Vermont, headquartered in the town of Brighton somewhere down a gated dirt driveway that leads off into some pines that looks more like the nondescript entrance to a sandpit than a government office.

Overlanding

There’s a fun hobby that’s abundant here in Vermont that always gets you near enough to some of the state’s best off-the-beaten-path places that most aren’t hip to. It’s called Overlanding, or, off-roading, and it can bring you to cool places like Lewis.

It’s something that I’ve dabbled with a few times with my brother over the years, starting out when we were late teens/early 20-year-olds when we started taking the family’s ’78 Toyota Landcruiser along gnarly mountain trails in the hills between Milton and Westford. For some reason, I couldn’t think about my trip to Lewis without thinking about this, so I decided to shoehorn it in this blog post.

The truck taking a muddy thrashing in the above photo was a more recent project of my brother’s – a 2 door, early ’95 project Toyota that was probably more work than it was worth. It was completely cut in half and welded back together, and all the parts came from Craigslist. It amounted to about a year of road trips, work, and headaches. But it paid off!

We rumbled in the cold and took it up bumpy logging roads and 4 wheeler trails in Vermont’s rugged north country; towns like gritty Johnson and the unassumingly vast spaces of mountainous Waterville and Belvidere – both far-flung villages that look like they’re still in the 1800s and are probably a picker’s jackpot. I still have flashes of us stopping at Tallman’s Store and rumbling down potholed route 109 and seeing the formidable wind molested haunch of Belvidere Mountain thick with snow and ridgeline alpenglow that blazed luminously.

Up in the mountains, we bumped and jarred around defunct mines, active sugarbushes, past 200-year-old cellar holes and slipped and slided up steep slopes, through stream beds, and passed cool hidden waterfalls and dead quarries – many of these areas used to be gores! It was a real thrill (and in the winter, was an activity specifically called ‘snow bashing’). If I had a metal detector, I’d probably bring that along too!

Sometimes you’d meet other off-roaders, pull over and chat about trail conditions, or get the details on the other’s ride. Other times you saw scuffed rocks or trees and knew some poor fella had to of done a real number on their vehicle. If you can make it happen, it’s a fun time, taking you places most folks don’t get to see.

It’s also a continuous mental and problem-solving situation, with the journey itself infused with self-reliance being the primary goal – so using your wits is recommend. Some of these trails aren’t easy to navigate. Another fun activity I used to do is to find some “dead roads”, a Vermont phenomenon where roads that were built in the 1700s and the 1800s have long been abandoned, but are still legal right-of-ways. Using old maps and tracking some of them down was pretty neat!

But honestly, the best part of it all? Overlanding and oddity hunting means spending time outside.

Here’s a Youtube video of some guys having some fun! I know this made me wanna get out for an adventure!

Since 2012, I’ve been seeking out venerable examples of Vermont weirdness, whether that be traveling around the state or taking to my internet connection and digging up forsaken places, oddities, esoterica, and unique natural features. And along the way, I’ve been sharing it with you on my website, Obscure Vermont. This is what keeps my spirit inspired.

I never expected Obscure Vermont to get as much appreciation and fanfare as it’s getting, and I’m truly grateful and humbled. Especially in recent years, where I’ve gained the opportunity to interact with and befriend more oddity lovers and outside the box thinkers around Vermont and New England. As Obscure Vermont has grown, I’ve been growing with it, and the developing attention is keeping me earnest and pushing me harder to be more introspective and going further into seeking out the strange.

I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to keep this blog going. Obscure Vermont is funded almost entirely by generous donations. Expenses range from hosting fees to keep the blog live, investing in research materials, travel expenses and the required planning, and updating/maintaining vital tools such as my camera and my computer. I really pride and push myself to try to put out the best of what I’m able to create, and I gauge it by only posting stuff that I personally would want to see on the glow of my computer screen.

I want to continuously diversify how I write and the odd things I write about. Your patronage would greatly help me continue bringing you cool and unusual content and keep me doing what I love!