Vermont’s visage is one of scenic mountains and an eye magnetic lack of industry, which makes the state a notable contrast from its neighbors. But a few decades ago, our Green Mountains were combed with industry that depended on the state’s naturally occurring topography and it’s profitable innards. Many of the state’s rural areas have once been cannibalized for their precious commodities that lay underneath the ground, and if you look below the surface, many small communities still bear the scars from irresponsible practices and their related pollution.

No one is exactly sure how copper was discovered in Vermont, but according to hazy hearsay, it’s inception to the state economy was pretty much circumstantial. Legend says that farmers and landowners in what’s now Orange County (or more specifically, Vershire) began noticing the indicatory rusty discoloration in snow drifts on their properties while out tapping Maple trees or out while fox hunting towards the late 1700s.

One story tells of a farmer’s young daughter falling into a hammock ( a raised mound of dirt) while out walking the family farm in Vershire, and coming back to the house with her leg covered in an orangy muck, which caught her father’s attention.

That discovery ensured that a few decades later, businessmen were compelled to begin mining for copper in Vermont’s newly emerging copper “belt”.

Though the boom was contained in a pretty small area limited to southern Orange County, its mines became fabled for a brief time for their voluminous outputs that took insufferable work to tease out, one of them becoming the largest copper producing mine in America for a brief time.

The northernmost was the Pike Hill mine in biblically named Corinth – the old name said to be chosen because of its establishment and reputation, so any new settlers would get the idea that the wilds up that way would be accommodating and amiable to them. Another guess is that it came from a village in old England, only, no settlers were ever recorded to have connections to that one, and the UK’s Corrinth is so small that even modern atlases don’t always pick up on it. As for Vermont’s Corinth, though, a lot of other United States’ Corinths were said to come from this one!

Not much remains of Pike Hill’s mine, except for a few scattered stone foundations and a very orange hillside scarred up by 4 wheeler trails off a tight dirt road.

Corinth town clerk Nancy J. Ertle answered my email to her ebulliently.

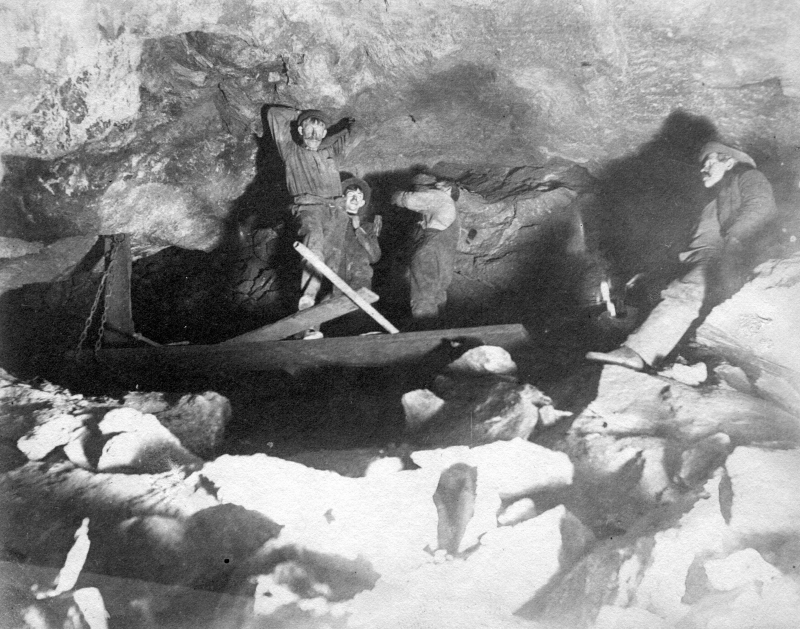

“I live up by the mines and actually have been in them. Which is really cool! We go in in the winter when the water is frozen and you can walk on ice since the shafts are full of water.” I’ll have to stop in and chat with her in person next time I’m in the area.

Vershire’s Ely Mine was said to have a more intriguing discovery. It was said that as early as the late 1700s, inconspicuous trails of sulphury smoke and fireballs were seen over the forests of John Richardson’s farm on Dwight Hill in Vershire. But it wasn’t until after a rainstorm in 1812 that would clear up any speculation, when his daughter Becky stepped on and sunk up to her knee in a mound that looked like a “burnt outcropping” while walking the property. Realizing she was stuck fast, she began to holler for help. When she was pulled out, her leg was found coated with an orange mud and the hole filled with an odorous sulphury mess.

Encouraged by this colorful evidence, in 1820, a group of local farmers got together and formed The Farmers Company and began purchasing mineral rights in the area in order to produce copperas. By 1833, the aforementioned Richardson farm was surveyed by an Issac Tyson, described as “probably the leading industrial chemist of the day”. Tyson was the first to attempt drilling at what would be known as the Ely mine. Around 1833, he started boring an adit (a horizontal tunnel) to intersect the vein from the southern side of the hill, but two years later and ninety-four feet without striking ore, Tyson’s partners lost faith in the project (possibly influenced by the financial panic of 1834) and pulled out despite Tyson’s protests.

But by now, the tantalizing word that copper was underneath Vermont’s hills was out, and more people wanted in. In 1854, The Vermont Copper Mining Company was created and immediately picked up where Tyson left off. They purchased the property for $1,000 and ironically, they only needed to dig an additional four feet in Tyson’s discontinued adit to strike the vein he was looking for.

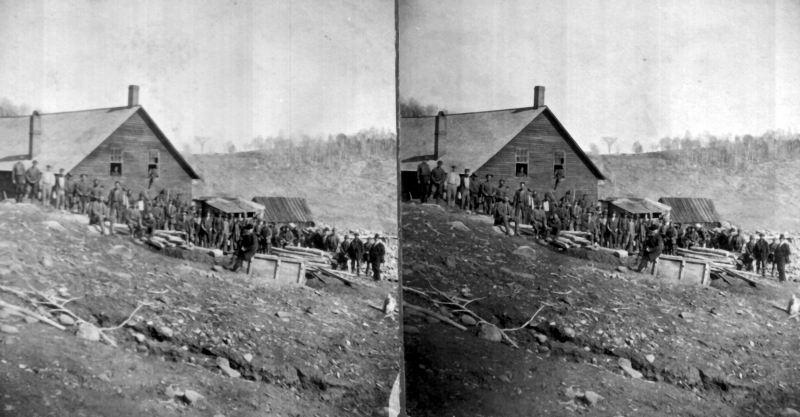

One of the original investors in the mine was a New Yorker named Smith Ely, who would eventually take control over the mine and company after the civil war, which produced a huge demand for copper. With a new national ban on foreign copper, the need for domestic production stirred an uproar. Under Ely’s leadership, the mine that now wore his last name became a significant operation and would grow to become the largest copper mine in the United States for a time, reaching a peak employment by November 1881 – of 851 curious and voracious miners.

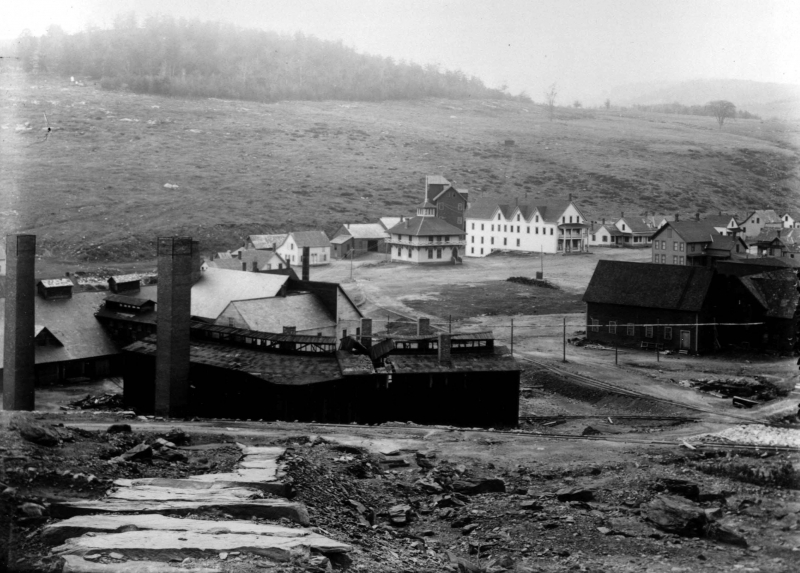

In 1876, Smith Ely’s grandson Ely Goddard would take over the mine. His first act of business was to change his last name to Ely-Goddard in honor of his grandfather. His next act would be to make himself more at home, by constructing himself a lavish vanity project in the middle of the village; a mansion which he named Elysium (pictured in the photo above, the white building with the central copula), a reference to the ancient Greek concept of the afterlife, and perhaps demonstrating some of his exaggerated swagger with a play on his last name. The mansion was regarded as one of the finest feats of architecture in otherwise hardscrabble orange county, and soon became a place where grand parties would be held where Ely-Goddard’s rich friends from New York, Newport RI and as far away as Paris would come and have nights of debauchery while the miners whose dwellings encircled the mansion enclave were close to starving.

The Ely’s entrepreneurial spirit earned them some lauded accolades in the Green Mountains, including Ely-Goddard being elected to the house of representatives in 1878, and the company lawyer Roswell Farnum being elected governor in 1880, which was no doubt a period that was very kind to the mining industry. Or maybe I’m just being cynical.

But having an upper hand in politics couldn’t save the mines against more profitable opportunities out west. As a result, the price of copper began to fall as domestic supplies increased. Mining in Vermont was hard. The deposit veins produced little copper that required more work than payoff to access, and most mines were far away from convenient transportation corridors. In 1881, Smith Ely sold his shares in the mind to Ely-Goddard and the newly in the picture Francis Cazin, a German engineer who planned on saving the mine by profusely dumping money into it. But it didn’t work, and Ely-Goddard blamed and fired Cazin, who sued the company in retribution.

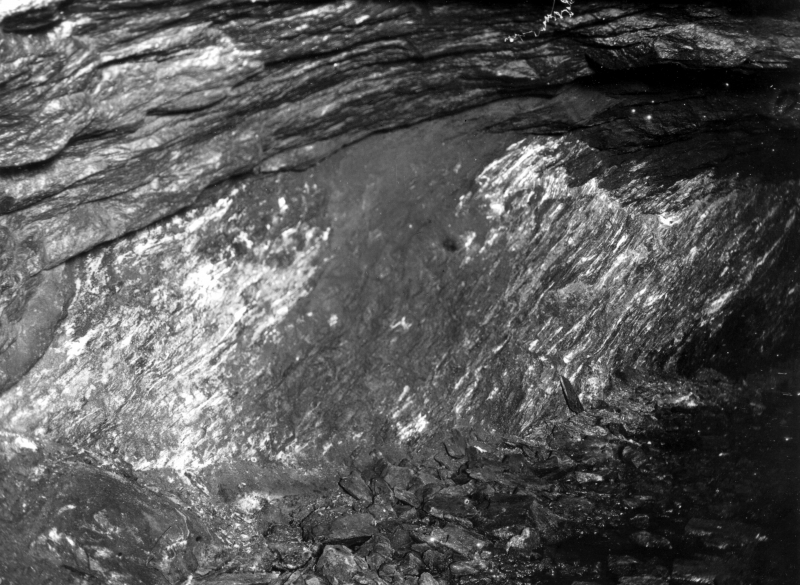

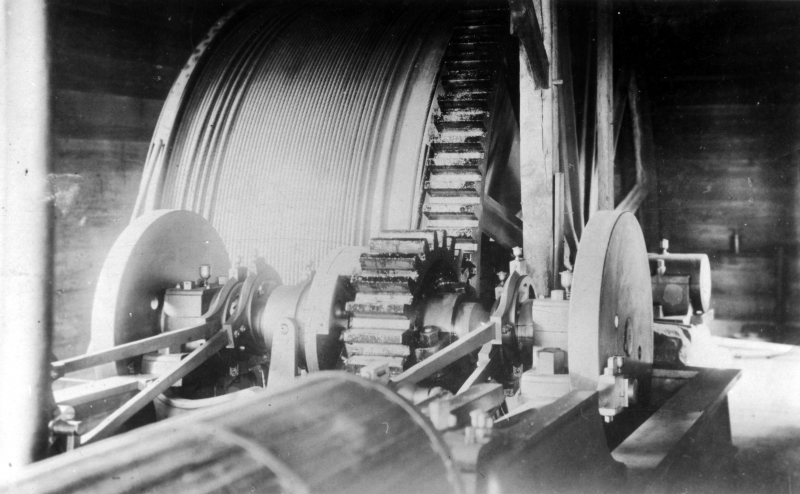

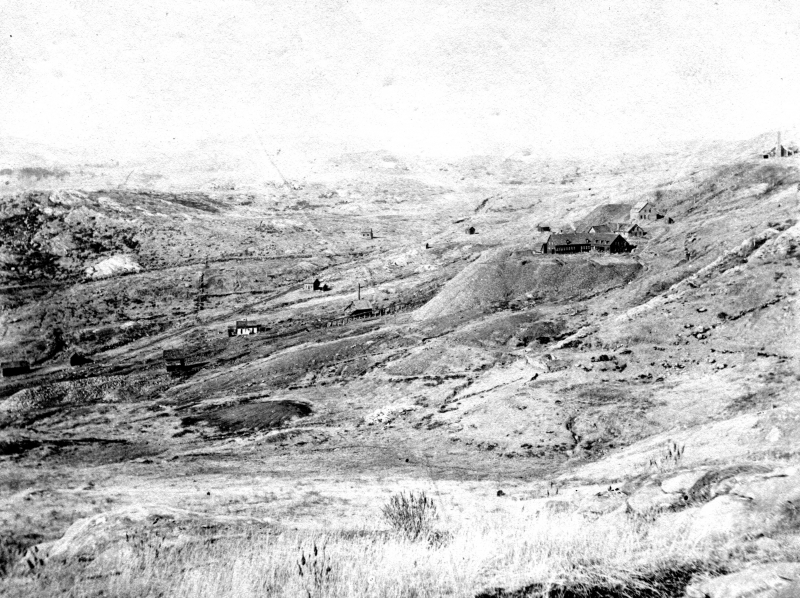

On June 29th, 1883, all the bad financial investments and a newly emerging series of lawsuits caught up with the company. By now, the Ely mine boasted the largest copper mining shaft dug in Vermont, unconfidently considered to be anywhere between 3,400 feet, to 4,000 feet deep. For a comparison, our largest mountain, Mount Mansfield, is 4,395 feet. But despite the efforts, only about 3% of what miners were carving out was actually marketable copper, and the cost of operations, such as hoisting apparatuses, pumps that kept the shafts from flooding and the tons of wood needed to burn to keep the smelting processes going, had drained their bank account.

Their solution was posting a sign telling miners that the mines would be closed until they agreed to take a pay cut, which of course didn’t go over so well. The miners who had already gone two months without pay, revolted in what is sometimes called The Ely War, which is both considered the most important instance of labor unrest in Vermont and to my surprise, almost never talked about. Having already worked for months without paychecks, the miners had reached their limits of toleration and went on strike. They raided the company store, started destroying company buildings in the village, acted without foresight and broke the pumps that kept the shafts from flooding to make the mines unprofitable for the owners, and stole all the gunpowder and threatened to do further extensive damage with it if they didn’t get their pay.

To add insurance, they all marched to Smith Ely’s house in West Fairlee chanting “bread or blood!” The startled Ely, who was desperate to get the angry mob off his lawn, assured them that they would all get paid. But instead, he sent out a distressful telegram to governor Barstow and the national guard was deployed to arrest the rioters.

The militia marched into Copperfield underneath the stars, found the strike leaders and arrested them in their beds. As the sun rose above the martian landscape around the mines and the other miners awoke from their beds, they saw their strike leaders indignantly being marched down the main drag in irons. The so-called Ely War was over. Another interesting account I found online told of a different, more earnest story.

On the morning of July 6th, 184 members of the national guard marched into Copperfield expecting to find an unruly mob of miners waiting for them but instead found eerily quite buildings built upon slag pile debris. The miners, who were waking up by then, noticed the national guard soldiers walking around town, and went out to converse with them. After telling them their grievances, the national guard sympathized instead of incarcerated and gave the miners all their food rations before getting back on the train.

As these stories often end, the miners were never compensated, and the company went bankrupt by 1888 because ironically, they weren’t able to meet their obligations because of all the damning facts pointing to the company’s inevitable death. And, the mines were now underwater.

Because the mine was now virtually useless, it changed ownership a few times with hopes of re-opening before becoming permanently defunct by 1920. Elysium was sold for $155 and moved to Lake Fairlee, which can still be seen today off state route 244, and the Copperfield Methodist church can now be seen in tiny Vershire village off state route 113, while the rest of the buildings became forsaken and slowly disintegrated to dust.

My friend Eric, a close friend from my college days, grew up in West Fairlee down the road from the Ely mine, which is how I found out about the place to begin with. So in the dying days of 2015, as the temperature dropped precipitously, we set out in his Subaru to go walk around his old high school stomping grounds.

Driving down state route 113 with Montreal’s Stars playing softly from his iPod, we entered tiny Vershire, a name that’s an agglomeration of Vermont and New Hampshire, and is either pronounced “Ver-shur” or “Ver-sheer”, depending on who you are. It seems like it’s a trivial bone of contention between Vershire-ites. After the closer of the Ely mines, Vershire lost scores of its population until it dwindled to just 236 inhabitants in 1960, making it the smallest town in already low populated Orange County. According to the 2010 census, the population has since grown to 730.

Off the town’s main drag, which is the destitute state route 113, there is an easy to miss intersection with an evocatively incongruous name; Brimestone Corner. While I’m not sure of the story behind this curious name, I have my own theory. There are plenty of locales in Vermont named after the Christian personification of evil, such as Satan’s Kingdom on Lake Dunsmore, and Devil’s Den in Mount Tabor, to name a few. Superstitious settlers gave the suggestive geography their names years ago, when remote and rough patches of wilderness were foreboding, shadowy and full of rocks which made farming almost impossible. It seemed to make sense to them that the Devil himself called these places home. However Brimstone Corner got its name, I love the fact that it still appears on modern day map engines like Google.

Death often ends a story, but in the cases of some forsaken places, they can also extend a bit in their celebrity. I’ve covered a few of them in this blog, and the Ely mine would fit right in I’d say. Exploring the historical oddity with Eric also meant that I got some of the inside details of it’s strange and seemingly nefarious local lore that has more or less simultaneously garnered such a reputation and earned it some infamy with area youth, curious visitors and allegedly bad dudes that aren’t necessarily connected to the mafia.

There’s a corollary in the world of abandoned mines that the empty real estate is a great place for humanity’s more ghastly truths. Apparently sometime in the early 2000s, vicinity pets began to go missing, mostly dogs. Eventually, curious visitors to the mine found several decomposing dog corpses stashed within Ely’s dank mine tunnels. Later, the pieces would be put together and it appeared that local boys had been kidnapping and killing their canine victims. I also heard that human remains have been found underneath Dwight Hill as well, but I’m not completely sure of the veracity of both these tales.

In keeping with both traditions of mine shafts being a desirable place to dump unwanted variables or pesky things that could be considered evidence and sometimes buried secrets are difficult to keep buried, there was a local man who made good profit a decade or so ago, by kindly offering to dispose of rural Vermont’s endless junked tire population. Only, he was just dumping them at Ely, which was already considered a Superfund site that the time, and was somehow caught and penalized. A huge mound of tires still sits towards the upper part of the property that ring a beaver dam below a steep birch tree clumped ridgeline. That part of the mine was eerily quiet, the only sound was our boots clomping through deceptive ground that was more mud than ground, the unmistakable odor of sulphury perfume inhaled by my nose that doesn’t belie the truth of the matter here.

Eric also recalls the plight of schoolhouse brook which formed the line diminishing edge of his backyard, and how he recalls fish swimming in its shallow waters as a kid, but as he grew and the river grew shades murkier, lifeforms were reduced significantly.

There was a strange beauty to the landscape though that also helped to establish the aura of mystery that tends to surround these sites. The ruins at Ely are a simple yet compelling depiction of our collective history here, a testimony to both prowess and irresponsibility. Not much remains at all of its legacy here because of a massive cleanup initiated in 2011, which I couldn’t help be a bit disappointed by, but in the end, there is something about these old mines and their stories that yield an irresistible intrigue to me. Oddly enough, I read that the property is also eligible to be inducted on the national register of historic places, but I’m a little lost as to what that distinction would actually do for the property.

Observing the beaver dam, I couldn’t help but wonder if it was around when the mines were active, or more of a recent addition after the chaotic operations became ghosts. Beaver dams are built to last by design, which makes them historical landmarks, and there are plenty of still existing ones that have actually predated many of our settlements.

The Elizabeth Mine

Though I didn’t largely cover the Elizabeth Mine in this blog entry because it’s already lengthy enough, Its very much worth noting. You can’t mention copper in Vermont without an acknowledgment of this place.

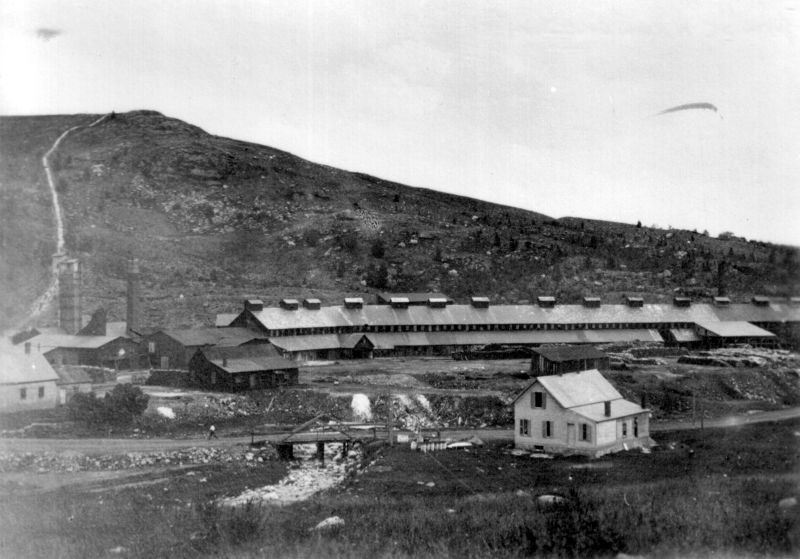

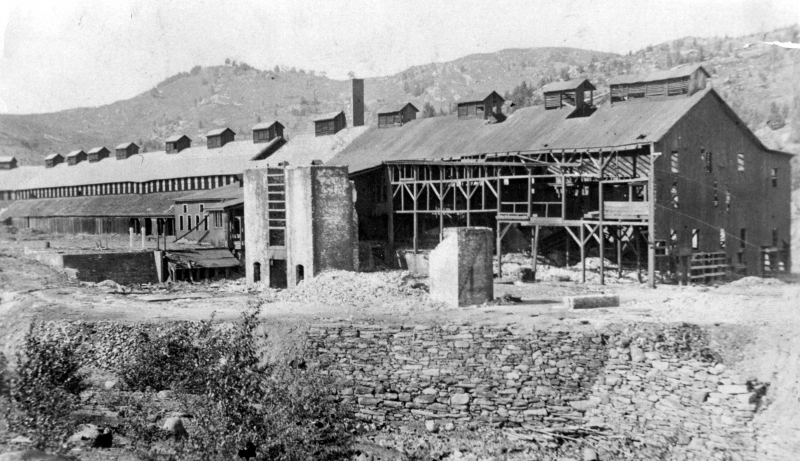

It holds the distinction of being the oldest running copper mine in Vermont, and once the largest in the country, running for 150 years before following the trend of Vermont’s other mines and closing for good in 1958. The property was also inaugurated into the Superfund family of sites and underwent a massive clean up in 2010, which also cleared out an awesome collection of buildings that looked like a Klondike ghost town.

But because of the mine’s unique historical status, parts of it have been left alone. Such as the mineshafts. Why? Because according to someone who wrote to me, this is the mine that supplied the northern/union army with copper during the civil war, which in itself is very cool.

Over my Instagram account, I spoke with my friend Mark Byland, who was part of the crew who installed solar panels over the now partially cleaned up mine site – and both of us were fascinated by the fact that Vermont had such a large production mine.

In Mark’s email to me, he said that the mine today is full of ticks, rats, and ‘other creatures’ that now occupy the nearly 6 miles of underground workings.

They set up their materials near one of the old dynamite shacks but were requested not to go snooping around the existing building, and there was a guy from the miners union posted on site as they worked to make sure there was no tomfoolery. But he does remember taking a glance at the completely exposed second floor and seeing a set of plans hanging around on a dilapidated desk in plain sight.

“There were a plethora of core sample boxes stacked up with more samples than you could imagine. Some really fascinating cross sections of what lies beneath” Mark enthusiastically wrote.

They were also told that the numerous shafts are all in danger of collapse, and were directed to stay out. Some of the shaft rooves had already collapsed, tearing open new holes in the ground. One of the project leads told a story about how he dropped a few rocks down one of the air shafts and never heard it hit the ground.

“I managed to find an old map of the shafts and it shows where they had

worked the interior, from the top down. Basically, that whole hillside, where the exposed pit is, where people go swimming in naturally exfoliating Ph 5+ water, is completely hollow underneath.”

Mark elaborated. “It seems like everything there is sort of protected by the most awful dread one could imagine. There’s an endless sense of spiritual presence, as the place is kind of one big gravesite for all the lives lost during its 200-year history.” Though Byland did note that it seemed that conditions at Elizabeth treated the miners far more humanely than what workers over at the Ely mine had to endure.

There was also a railroad that continuously ran from the top of the mine to the bottom, delivering ore to the processing facility. Some parts of the train cars and the engines are still junked somewhere on the mine property to this day.

Not much of anything remains of the Elizabeth, apart from a uniform green state historic marker on aptly named mine road in tiny South Strafford and a few uninteresting but politely demolished foundations.

But it’s the colossal open cut mines, dubbed to the point as the north and south cuts, that still remain on the property that are worth the surprisingly steep and deceptive hike up scrapped rock faces where former tailings piles were left, to the edge to gaze down at these huge and dangerous big digs of showmanship. Before the ruins were essentially dismantled, some lucky folks admitted to finding good-sized chunks of pure copper ore there were still there.

The south cut is known by cavers as quite the challenging adrenaline rush, and the north cut which is a more eroded copy of the south cut, is flooded and draws cliff jumpers and people looking for a place to cool off during the summer.

To get an astonishing idea of just how much waste this mine generated, subsequently left behind and then was cleaned up – check out Dave Gilles’ bewildering photo of the mine tailing waste dunes left on the nearby hillsides that come in a crayon box of colors. There were a lot of his photos geotagged over the mine site on Google maps.

On the backroads that serpentine the hills and hollows around Vermont’s first big dig are the remnants of ramshackle old row houses for employee lodging and assembled tar paper shacks where former miners and present old-timers refused to up and leave after the mines closed in the 50s – vowing a cryptic Yankee stoicism about exactly what kind of things went on up there…

My ending spiel on all this is, well, I just thought the place was fascinating. 1000 feet deep and 6 miles of tunnel workings. That’s some shit. Right under my boots.

Sources/For More Information

Lots of research materials went into writing this piece, including:

EPA Superfund Ely Mine Site | EPA PDF booklet on the Ely Mine, which features both a handy map of the site as well as a map that illustrates how the acid drainage runoff effects the area watersheds.

http://www.usgennet.org/usa/vt/county/orange/vershire/

A short history of the Ely Mine by Paul Donavan

The Ely War, VPR | The Ely War, Virtual Vermont Internet Magazine

The blog, Vermont Deadline, which I just pleasantly discovered.

Paul Donavan, a Vermont mine enthusiast, has a very cool website that includes his photographs of his ventures into the mines, as well as a great drawn map of Ely mine’s subterranean passageways. This gave me a good idea of the lay of the land. **I’d especially recommend my favorite of his photos, a set of slimy and disused rails still can be found underground in the Ely mines.

UVM Landscape Change Program, which is becoming one of my go-to sites for historical photographs and Vermont history.

I was very interested in exactly how copper was made, and got a good amount of information from this site

For other copper or Vermont enthusiasts like myself, you might enjoy this good documentary on copper mining in Vermont:

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my amazing fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations through out the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4