Last weekend, I took a road trip with a friend to The Borscht Belt, a tongue-in-cheek colloquial moniker given to an area of New York’s Catskills Mountains interspersed with decaying hotels from a bygone era.

In the 20th century, New York’s Jewish community were being battered with a growing antisemitism inclination which shunned them from many mainstream hotels and vacation destinations.

That well-realized awareness encouraged them to cultivate their canny, and build a destination of their own. The Catskill Mountains a few hours north of New York City became their prospective topography that would be superimposed with lots and lots of blueprints.

Many establishments started out as simple farmhouses that offered kosher meals and a place to sleep, attracting mainly urbanites who wanted to part from the din of a city crawling with bodies. Other early attempts at tourism capitalized on the mineral springs fashion of the Victorian age.

It seemed like these investments were working, because around the 1930s, the area began to turn celebrity.

A sundry of small hardscrabble Catskill towns began to slip into destination communities as those boarding houses and cabins began to transition into increasingly lavish, all-inclusive resort hotels that sprang up on former farms and woodlots.

The emerging realm took on a few epithets, most popularly known as “The Borscht Belt”, after the traditional sour soup brought over by scores of eastern European immigrants who settled in New York City. The area was also slanged as “The Jewish Alps” and in Sullivan County’s case, “Solomon County”.

As time progressed, some places became so popular that private airstrips were being envisioned so they could accommodate a predicted increase in air travel from the city. The most revered appeal of the Catskills was that many of these resorts offered upper-class amenities and made them accessible to folks that normally couldn’t afford those luxuries, and as a result, other non-Jewish proletariat started becoming hip to the region.

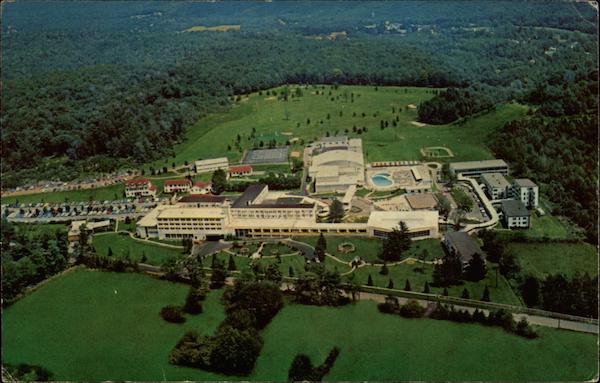

The Pines was one of those hotels, once beloved, now moldering in the presently tiny and depressed little village of South Fallsburg.

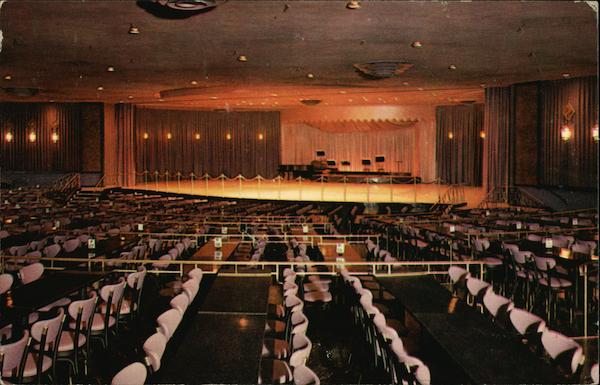

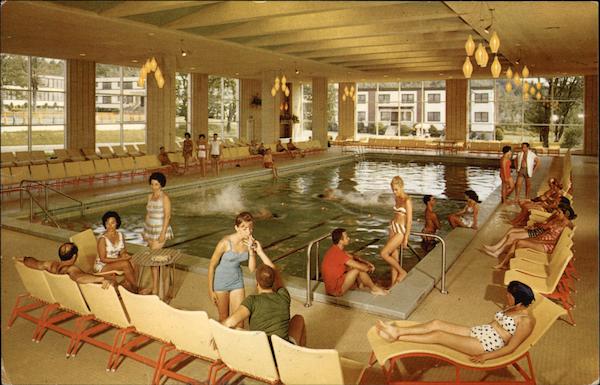

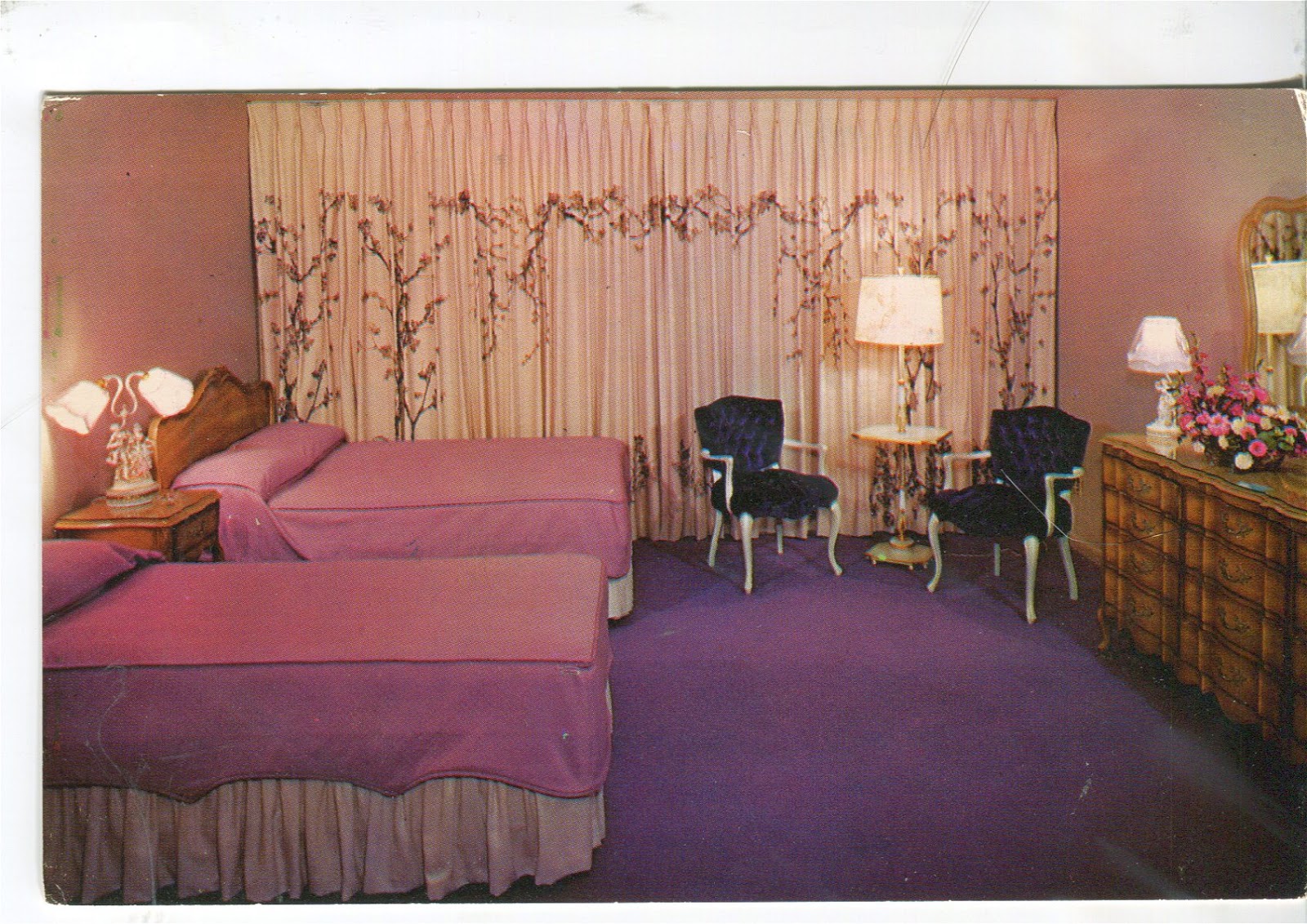

Existing since 1933, The Pines wasn’t one of the largest Borscht Belt resorts, but it was arguably one of it’s grandest. It grew to offer 400 rooms, a golf course, tennis courts, indoor and outdoor pools, a ski chalet and trails, an indoor skating rink, conference rooms, a nightclub and theater that hosted notable Jewish Alps entertainers of the day like Buddy Hackett and Robert Goulet, and a restaurant and bar.

The Catskills popularity found its pivot point during the 1970s, when social changes stepped out of the throes of the fight that many younger members of the Jewish culture no longer had to face as their parents did.

That, and cheap air travel could take people to other places for around the same price as a trip upstate. Now, people could go to Florida or Europe and didn’t need to settle for the Catskills. Ironically, even the Adirondacks, the loftier and bumpier part of upstate New York, was still increasing in popularity, leaving the Catskills to corrode in rust and sorrow.

The Pines’ story seems to end like most of these stories do. The sprawling hotel was sold in 1998 and bought by The Fallsburg Estates LLC, who wished to revitalize the 96-acre property, and, in addition to revamping the ski hill and golf course, build shiny new condos over the ramshackle hotel. But by 2002, they filed for bankruptcy, which is consequently why the hotel is in the deplorable and vulnerable state it’s in today.

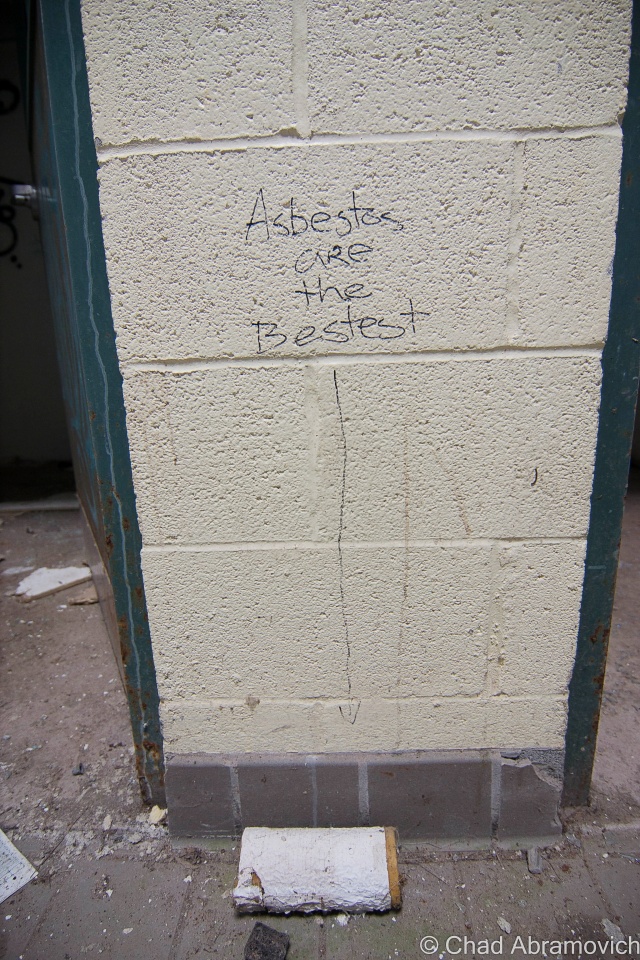

The remnants of the Catskill craze are still around, even if the craze isn’t. Today, the region is littered with abandoned properties – fantasies of blight whose visages bear slovenly expressions that welcome vandals, explorers, arsonists, scrappers and teenagers who are excited by the prospect of a paintball game or a place to drink cheap beer.

Arriving in South Fallsburg, I felt awkward driving around it’s deserted residential streets. Much of the area looks strangely incongruous, like a mockup community built by the government during the cold war that was awaiting the detonation of a nuclear bomb. The weird inner city like apartment blocks sitting in the woods were oddly desolate and forlorn looking, and the increasing amount of signs in Yiddish further sent me a feeling of dislocation.

Hiking up through the woods on a great 63 degree October afternoon, myself and my friend soon found ourselves staring at the brooding and ugly ruins of what was left of The Pines, and there wasn’t all that much. I had came a bit late, after it’s exploration heyday it seems, leaving me with what remained of it’s rotting bones.

The old hotel was absolutely trashed, being inside was like stepping into a rotting cave. The perpetually soggy carpets and dripping water immediately soaked my boots and the air was absolutely foul without a respirator mask.

Some levels had entirely collapsed, while other wings were more hole than floor. Moss, mold and plant life grew wild on the carpets and walls. Some rooms were completely destroyed, while others were strange enclaves of preservation, the difference at times depended on which side of the hallway you were on.

Mimicking the residual motions of the long gone guests, I spent several hours walking around its dark passages, feeling disparate nostalgia for a time I never even lived through.

Scrappers had ransacked the surviving sordid buildings for any valuable materials they could rip out of the walls or ceilings. Evidence of squatters camps could be found in a few rooms, which was a real poignant and sobering sentiment that there are some who do spend the night in this grim place, leprous with mold, rot and water damage that was beginning to make entire buildings buckle and bend as sections begin to lose their ability to do what they were designed to do.

A few different arson attempts were successful around 2003 and 2007 and consumed a few smaller outbuildings. Later, the indoor pool, theater, and indoor skating rink were razed, with an implied intent that the rest of the property was soon to follow. But demolition was halted, and the property sits in perishing limbo, somewhere between what it once was, and whatever it’s turning into.

Here is a promo made around the 1980s I found on Youtube, to give you an idea of what this place used to be like.

My talented friends at Antiquity Echoes made this great edit of their exploration to The Pines a few years ago, and their thoughtful camerawork shows much of the hotel that has long vanished.

In the 1990s, convention centers were becoming Catskills de rigueur, so many hotels, including The Pines, built them up on their properties.

In the 1990s, convention centers were becoming Catskills de rigueur, so many hotels, including The Pines, built them up on their properties.

Autumn just makes road trips better. Driving north towards Middleburgh, we were immersed deep within the surprisingly vast destitution of the Catskill Park Wilderness, which meant driving on curvy paved back roads around beaver meadows and rolling hills all dying in a brilliant uniform yellow for several hours, occasionally passing through a small town that was a collection of unmaintained old houses and maybe a church. There are no gas stations in the Catskills, which always makes my anxiety glance at the gas gauge needle and sucks if you need a bathroom.

Another noticeable difference between the Catskills and Vermont, besides the singular foliage color of yellow, was that while I may encounter 3 deer wandering out into the middle of the road in 3 years in Vermont, in the Catskills, we had to slam on our breaks for 8 deer in a single drive.

Eventually, we happened upon a state park and camped out for the night on the last available night of the state park season. The temperature dropped into the teens and I was kept awake all night by wailing coyotes and things that scampered through the dead leaves around my tent. But with a cozy campfire and some microbrews bought at nearby Middleburgh; a startling and mood improving oasis of blue-collar businesses and a Christmas light covered main street, it was a great night. The next morning, I was as rested as sleeping on a tent pitched on a gravel bed in 18-degree weather would get me, and we were off.

Gross at Grossingers

About a half hour from The Pines sat another enormous abandonment where I briefly stopped to photograph. This hotel was legendary and was arguably the hotel that became the representation of the region, growing to a size of 35 buildings on 1,200 acres. In 1952, it would enter its place in worldly accolades as the first place that used artificial snowmaking on its ski slopes.

So large in dimension and repute was this hotel that a private airstrip was once constructed to handle predicted private aircraft traffic that never came.

Grossingers’ rise and fall echoes The Pines’ own tragedy and became a ghost just as fast as it triumphed.

The prodigious property is a victim to one of the grimmest truths of reality. It’s so deplorable after two decades of raving and destruction that its disgusting ruins were sadly a disappointment to walk through – a sad fall and postmortem.

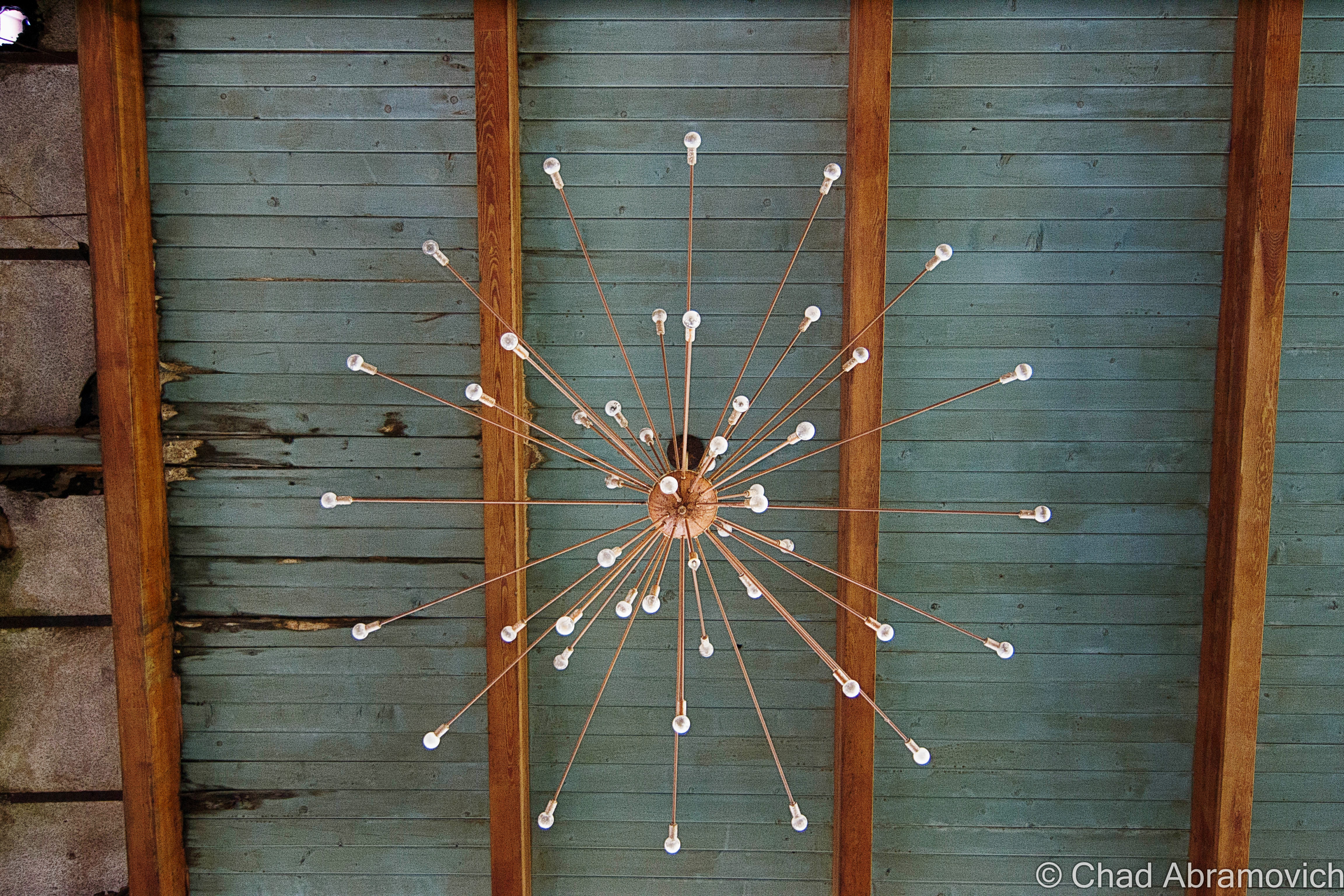

That is, except for its extraordinary natatorium.

The mid-century marvel was under the weight of its silence, not even the birds were chirping as I walked around the massive space. Though the electricity was shut off decades ago, the atrium’s great design ensured the place was nicely lit up by plenty of skylights in-between some striking starburst chandelier style light fixtures from the 1950s that were still shockingly preserved . Walking around coats your boots in slick sludge and stubble white mold that has been reclaiming the buckling pool tiles. The pool itself is a chaise lounge graveyard, tossed into some murky filth and curating rot that has collected in the Olympic-sized pool’s deep end.

This place has achieved legendary status for explorers, photographers and curious visitors all around the east coast. A visit here jestingly pushes your explorer legitimacy card. Just before I walked in with my camera, a bunch of teenagers were just finishing shooting a music video here.

The most troublesome part of my visit here was actually trying to leave. When we were walking back to the car, my friend and I were inducted into a circumstantial game of face off with a vicious dog, who was creating a raucous of barking and snarling at our presence walking down a quiet back road with our cameras.

After about 20 minutes or so of keeping our tentative distance and wondering if he was going to dash off the front lawn in our direction if we got any closer, it walked around the back of the house and oddly, disappeared. No one came outside, and we heard no doors opening (we were that close). We waited another five minutes or so, and finally decided we were going to chance moving forward. Luckily, we made it safely back to our car with our internal organs in their places.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my amazing fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations throughout the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!