On my quest to discover Vermont curiosities, weirdness and mysteries, I made the mistake of overlooking my former hometown of Milton, a community steeped in stories and legends. But Milton presented a challenge to me. While some lore seemed to be well recited among local residents, the actual stories behind the stories simply weren’t there. Over the past year, I began talking to people, writing down notes and choosing things I wanted to research further in detail. I wanted to bring these great stories to life once again, and through arduous research, I was finally able to fill in some missing pieces. This will be the first in what will hopefully be a few entries on Milton mysteries.

A year ago, I stumbled upon an old photo which fascinated me. The photo depicted a large mound of earth dubbed as “The Indian Mound”, it’s vague description locating it somewhere near the shores of Lake Champlain. Was there an Indian Mound in Milton?

I’ve traveled the many dirt roads of West Milton all my life, but have never seen a geological formation like this before. If there was such a mound, surely it would be of great importance. Why was it so discrete? Do people know of its existence? And, the most heavily weighed question, where was it?

Speaking with Lorinda Henry from the Milton Historical Society, she explained that the mystery about the Indian Mound was far greater than the information about it.

After digging through stacks of papers and unlabeled binders at the historical society, I was able to find my first clue; that the mound was located down near Camp Everest in Milton, a hidden area off a series of remote back roads that don’t receive much traffic other than locals, and a name that may very well be lost to many Milton residents today.

A vestige of the days when Milton was a summer tourist destination, Camp Everest was just one of the many large camps that would be built up along the shores of Lake Champlain.

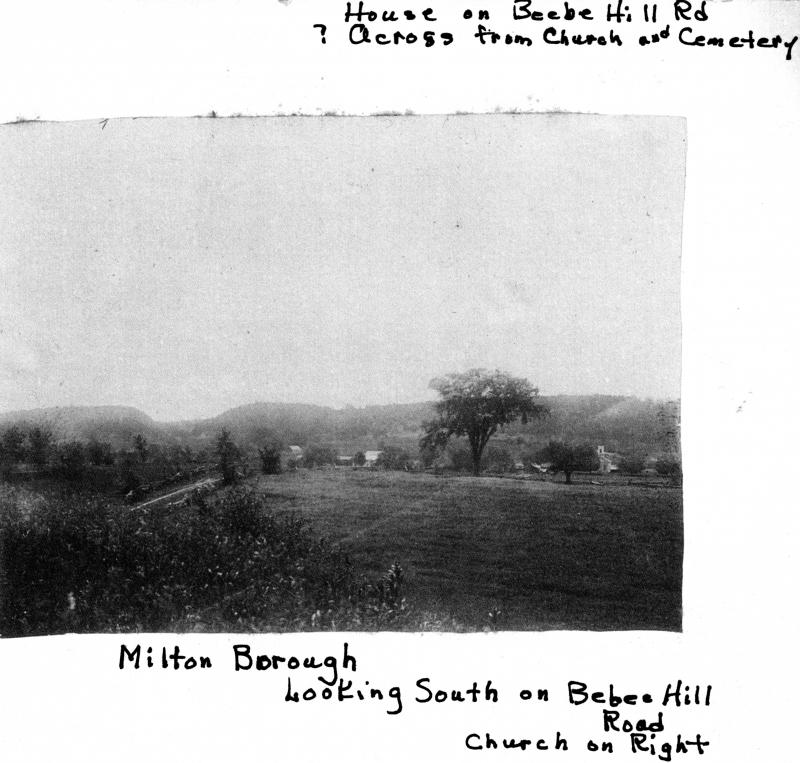

In the mid 1800s, camping in summer cottages and tents would draw people to the shores of Lake Champlain. Milton’s lakeshore was a murderers row of natural beauty, complete with stony beaches, Eagle Mountain’s giant looming rocks, marshlands, and deep forests. Land owners began converting their properties into camps to take advantage of this, and as a result, camps Rich, Martin, Watson, Cold Spring, and Everest would open for business.

The camps all had farms, providing them with fresh food. Many of them boasted luxuries such as proximity to clear mountain springs, and the availability of fresh cream, eggs, milk and vegetables. The properties also offered many amenities such as recreation halls, lawn sports, fishing excursions and hayrides. Some camps even had handsome hotels built extravagantly and symmetrically, standing above the waters, with classic New England verandas, conical towers, decorative dormers and dramatic features that accentuated different sides of the buildings, almost to a point of tactility. Old advertisements for Camp Watson even boldly claimed that they had “positively no mosquitoes” – although, being quite accustomed to Vermont summers, I can’t help wonder just how they went around keeping that promise.

The area along the lakeshore became known as Miltonboro, which included schoolhouses, a church and meetinghouse which catered to the campers and locals who didn’t want to travel all the way to Milton village. Today, most of Miltonboro has vanished, leaving only a small cemetery ringed by a stone wall, and a name on a map.

Camp Everest, the southern most of Milton’s lakeshore camps, was established in 1878 by Zebediah Everest and A.W. Austin, and they couldn’t have chosen a more splendid location. Bordered to the south by serpentine marshlands that now make up the Sandbar Wildlife Management Area, and to the north by the dizzying ledges of Eagle Mountain, with a sweeping view of South Hero island and the Adirondacks across the lake. The camp included a camp house, bowling alley and eight cottages, occupied by both family members and renters. It was here at Camp Everest where the alleged mound was located.

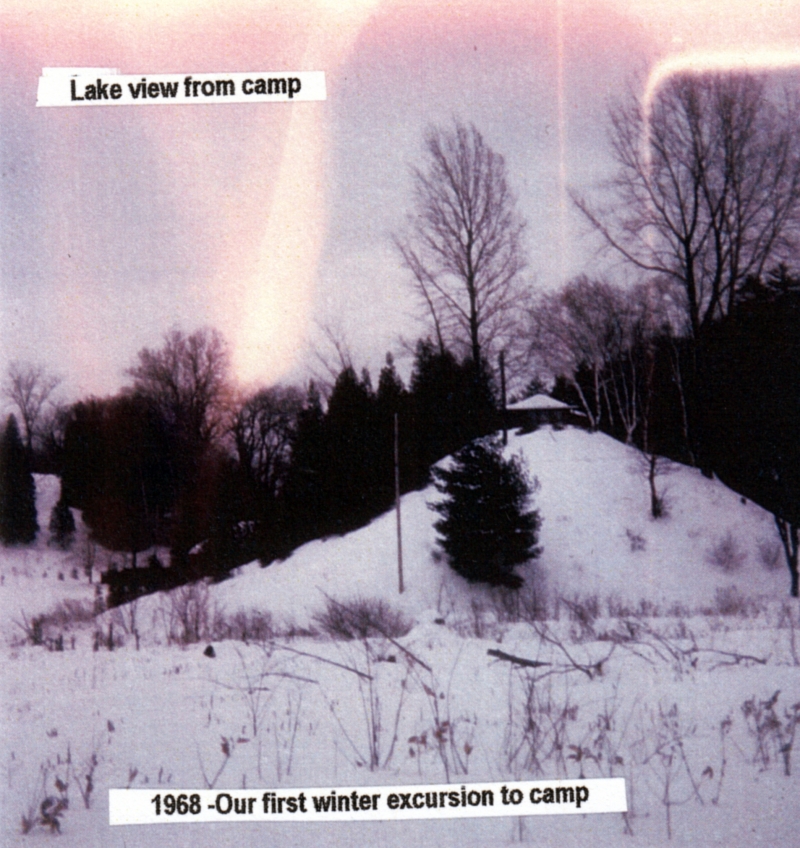

However, the information I read didn’t portray the mound as culturally significant, but rather in a bureaucratic sense – it was simply a piece of property. A camp was built atop the steep hill in 1927 by the Hutchins family, and named “Indian Mound”, perhaps romantically after what the earlier campers viewed the mound to look like. I was able to reach out to Barbara Hutchins, whose family originally owned the camp, and she was kind enough to give me further information.

She explained that the mound itself was probably formed during the glacier age, most likely a remnant of the Saint Lawrence Ice Sheet that once covered this part of North America. UVM did some digs around the mound in the 1950s, and found nothing of Native American significance, but they did find some old sea shells and fossils, evidence of the Champlain Sea, the tropical sea which covered what is now Vermont millions of years ago.

The Hutchins eventually sold the camp, and lost track of the property. I was able to dig up choppy pieces of information at the historical society – listing the names of various people who leased the camp throughout the years. The dates got sparse after 1970. Eventually, the information just seemed to cease. So, what happened to it? Was it still there?

Lorinda Henry explained that the state of Vermont wanted to hack apart the mound and use it to fill in a nearby swampland in 1948, but further research told me that because the area was prone to flooding, they decided not to, because the amount of dirt they would have gotten from the mound would have most likely been lost within a few years, leading me back to my original question.

The existence of an Indian Mound is also curious, because Vermont was never thought to be associated with mound building Indians. But then again, at one time, it was thought that Native Americans never settled in what is now Vermont. But Milton farmers would constantly find artifacts and arrowheads while clearing and plowing their fields. Arrowheads were also allegedly found when Andrea Lane, a small neighborhood off Route 7, was being constructed years ago. Lorinda Henry explains that because of native traces in the area, there are parts of the neighborhood that can’t even be developed because of archaeological significance. If that myth was debunked, than would the presence of an Indian Mound be that hard to believe?

On a breezy August day this summer, I took the beautiful drive back down towards Camp Everest, with the intention of solving this mystery. The camp is much different from it’s heyday, now a series of private camps, owned by various people. The bowling alley and other amenities have long vanished into history and the creeping forests.

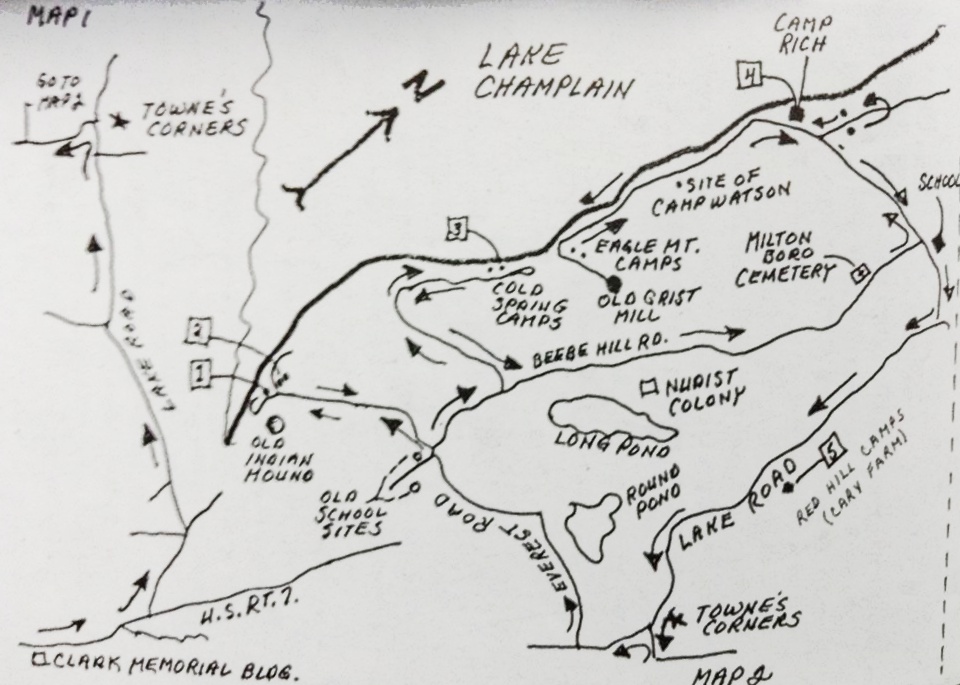

With the hand drawn map featured above in this post as my only reference, I scanned the roadside and across the many meadows bordering the area, but the imposing sight of the Indian Mound was never seen rising above the various clover filled fields or cedar forests near the roadside. I ran into several people, some jogging, others washing their SUVs in their driveways, and they were all happy to talk with me. But sadly, none of them knew about an Indian Mound or a camp of the same name. Some were out of staters and weren’t aware of the area’s history. But then again, a great deal of the area’s history has long vanished over the years.

From the map, I was able to sort of pin point the general location of the mound, but the area is much different than when the picture was taken. I had assumed, the mound might be still existing, now deep in the woods and covered in vegetation. But shortly after publishing this blog entry, I stumbled upon some further information.

Laurie Scott, who is an Everest, explained to me that the mound was eventually purchased by the grandson of the Hutchins family. The Everest’s lease most of the land where the camps sit, but her grandmother, Ethel Everest, sold the mound to them. The mound and the camp are still there, and as I assumed, is now obscured, hiding successfully behind a Vermont forest – an ideal getaway.

An interesting footnote to this story is that while trying to solve the mystery of this “Indian Mound”, Barbara Hutchins recalls that she heard there were a few other professed Indian mounds somewhere in Milton as well, but as for their locations, she doesn’t remember, leaving this intriguing mystery currently ongoing.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my amazing fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations through out the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4