“NEW ENGLANDERS They buried their emotions deep, Long years ago, with care; And if a stranger dares to dig He finds but granite there. — Catherine Cate Coblentz — Driftwind, May 1925”

A few days ago, I was traveling through New Hampshire’s White Mountains, a compelling region that I wish I had taken the time to explore more of when I was a college student in the Northeast Kingdom, far before the ugly reality of adulthood trimmed the fat off things. While Vermont tends to have a more gentle feel at times, New Hampshire is crucially different, it’s north country is essentially one giant patch of wilderness, which some say is roughly the size of Wales.

Part of the great Appalachian chain, it’s difficult not to be in awe of the rugged magistery of the White Mountains, whose hulking mountaintops rise out of view above the clouds, or the deep V-shaped natural excavation of Franconia Notch, it’s walls carved from the oldest rocks around.

The small town of Bethlehem, New Hampshire, has been around since 1774, and in the last days of 1799, it would adapt it’s current moniker, shared with the city of the same name on the other side of the world, though the origins behind the naming of New Hampshire’s settlement are a bit of a mystery. A drive down Route 302, the main drag in town, reveals one of the most architecturally impressive Main Street’s I’ve visited. A great collection of showy Victorians with some of the most ornate and complex woodwork that I imagine a human mind could ever devise. Busy roof lines punctured by wandering tactile patterns that sat next to humble Bungalows that have been very well preserved. Bethlehem’s exceeding aesthetics can be owed to the town’s heyday as an early tourist destination.

In 1805, the Old Man Of The Mountain was discovered, and by 1819, a path was created that carved its way up to the summit of Mount Washington. The White Mountains, their fresh air, craggy and almost daunting landscape and the mystique of their geographic curiosities were beginning the shift into a tourist area, and Bethlehem found itself conveniently in the middle of it’s many prominent attractions, which proved to be good for business.

In 1867, the railroad came to town, bringing tourists from the urban hubs of Boston and New York City. By 1870, a building boom period began, which would eventually create 30 grand hotels that lined Bethlehem’s streets which were all fiercely competitive against another. Each establishment tried to out-do each other in garish grandness and opulence, and they had to, because with a lodging bubble, standing out from everyone else was paramount.

Seven trains a day roared into the village, dropping of scores of passengers at five depots. Bethlehem must have been doing something right, because eventually, well-heeled east coasters took notice of the mountain town and decided to build their “summer cottages” here, which were blown up to colossal sizes and scaled up the hillsides that rose out of town. This included the likes of the famous Woolworth family and the enterprising swindler P.T. Barnum, the fellow who allegedly popularized the phrase “there’s a sucker born every minute”.

So many affluents would build here that an event called “the Coaching Parade” was conceived, which was pretty much those aforementioned rich folk flaunting their wealth and by ornamenting their carriages as ostentatiously as possible, and then literally parading them around town, which drew larger spectator crowds by the year, and led Barnum to call “the second greatest show on earth”.

But the decline of the White Mountains would have the same story that parallels other American vacation destinations of the same era and caliber; the rise of the automobile in the early 20th century would be the beginning of the end, as tourists were now no longer limited to only seeing places the railroads could bring you. When the automobile and their infrastructure worked its way up into the formidable highlands, the grand hotels eventually became ghosts, and the tourism culture changed to what pretty much is today.

One of these hotels was The Maplewood.

Opening in 1876, this hotel would soon become a showpiece, your textbook example of an incredibly lavish 19th-century resort which unabashedly marketed itself as “The Social and Scenic Center of The White Mountains”. It would eventually grow to ginormous proportions, encompassing its own 18 hole country club, casino, cottages, and was served by its own train station, Maplewood Depot. I guess I can see how their claim could hold it’s own. As a friendly New Hampshirite pointed out to me; in the glory days of rail travel in the White Mountains, the small Victorian station rivaled the most revered and fabled of north country stations, such as Crawford and Fabyan.

Maplewood Depot was abandoned in the early 20s in the wake of the automobile, and the hotel it served would function for a few more decades, before burning to the ground in January 1963. Today, the grounds have been revitalized as the Maplewood Country Club, with striking views of the Presidential Range. But sitting in the woods behind the links, the old train station can still be found, now leaning at a dramatic angle in its slow decay, wasting away in silence as the town thrives around it.

Most of the details depicted in the postcard, such as the expansive porches and apex tower have long faded into postcard memory. The former railroad line had it’s tracks pulled shortly after the station went defunct, but the right of way can still be detected, a ruler-straight path that is slightly less overgrown than the woods around it.

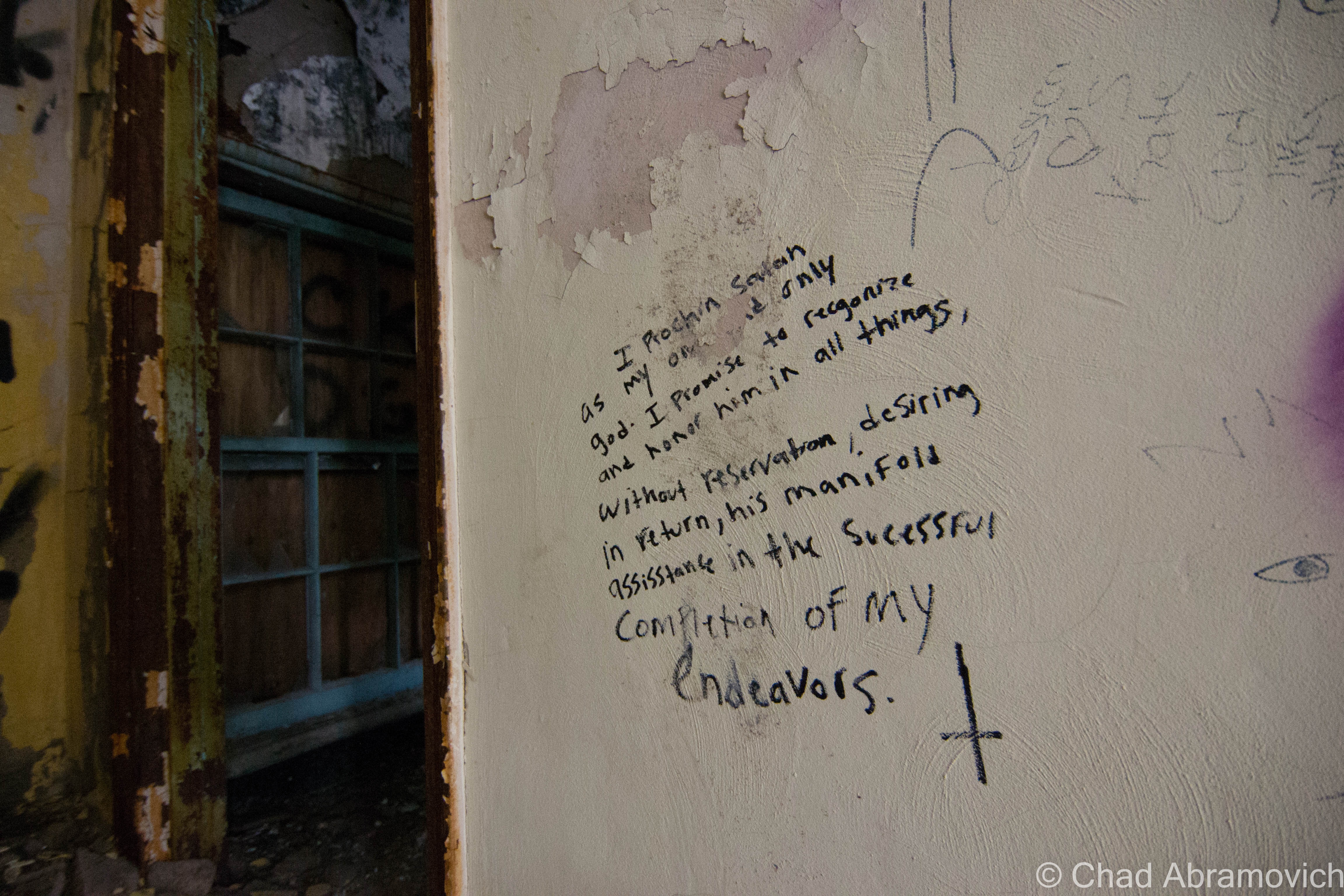

The station truly appears ghostly, skulking in the middle of the woods. Minus a few new-ish looking armchairs that have been toppled over, and most likely an addition to the building after it’s abandonment, it’s completely hollowed out, with empty doorways and tall, narrow windows. Inside, time has not been kind to the wooden structure. Much of it had long succumbed to weather damage and vandals, and portions of the original wooden floors had been ripped upwards as the building slowly sagged over the years, forming a jagged rip that ran the partial length of the room. I was a bit surprised at how clean this place was still, completely void of the graffiti and beer can piles which are found in many abandonments. I was still able to climb the narrow wooden stairs that curved around a brick chimney, revealing three rooms that were more or less intact, apart from some holes in the floor.

It’s a spooky place, especially as the winter winds hit the building, creating strange noises. I’m sure it takes on a far different atmosphere once the leaves fill out on the trees, blocking out even more light from reaching it. It’s almost startling to think about the fact that this place used to be a train station, and today it’s nothing but a trembling corpse that gives almost no clues to it’s former life. And at the rate that the place is leaning, I’m rather amazed that it’s still standing.

Maplewood was also apparently featured in the short concept film American Ruins, and after glimpsing the short trailer, it’s completely sold me. The effects and videography are mind blowing, which no doubt took hours and hours and hours of patience, producing and editing. Maybe someday I’ll aspire to creating something great like this.

[vimeo 25832079 w=500 h=281]

Over The Notch

Route 3 used to be the main route to get from the top to the bottom of New Hampshire, and still pretty much is, though it’s a bit quieter today in light of the construction of Interstate 93 which practically parallels the road. Both routes are pushed together when they run through mountainous Franconia Notch, joining to form the Franconia Notch Parkway, the main access road to all of the scenic points in Franconia Notch State Park, and the tourist attractions and motels farther south in the town of Lincoln.

Passing through the notch, I couldn’t help but gaze at the jagged stump where the Old Man of The Mountain used to be, now being battered by fierce mountain winds and the puffs of snow spray they send. The famous rock profile crumbled in 2004, and after much controversy, the state decided not to synthetically re-create it. Despite the formation’s disappearance, the Old Man is still used as a state marketing icon, and can still be found awkwardly on a variety of things from license plates to state route shields. It will be weird to think about there being a day where no one remembers seeing him in person.

In Lincoln, I stopped at an Irving Station to get gas and a coffee, and got an unexpected surprise in the form of a rather large mural of what looked like a seemingly friendly alien who was hitchhiking, which took up a rather large chunk of wall near the entrance of the store. Not exactly what I’ve came to expect from a stop at a gas station. On the top of the painting were the words; “First Close Encounter of the Third Kind, Betty and Barney Hill, Sept. 19th, 1961.” I recognized the names. The Barney and Betty Hill abduction case is the most infamous in all of UFOlogy.

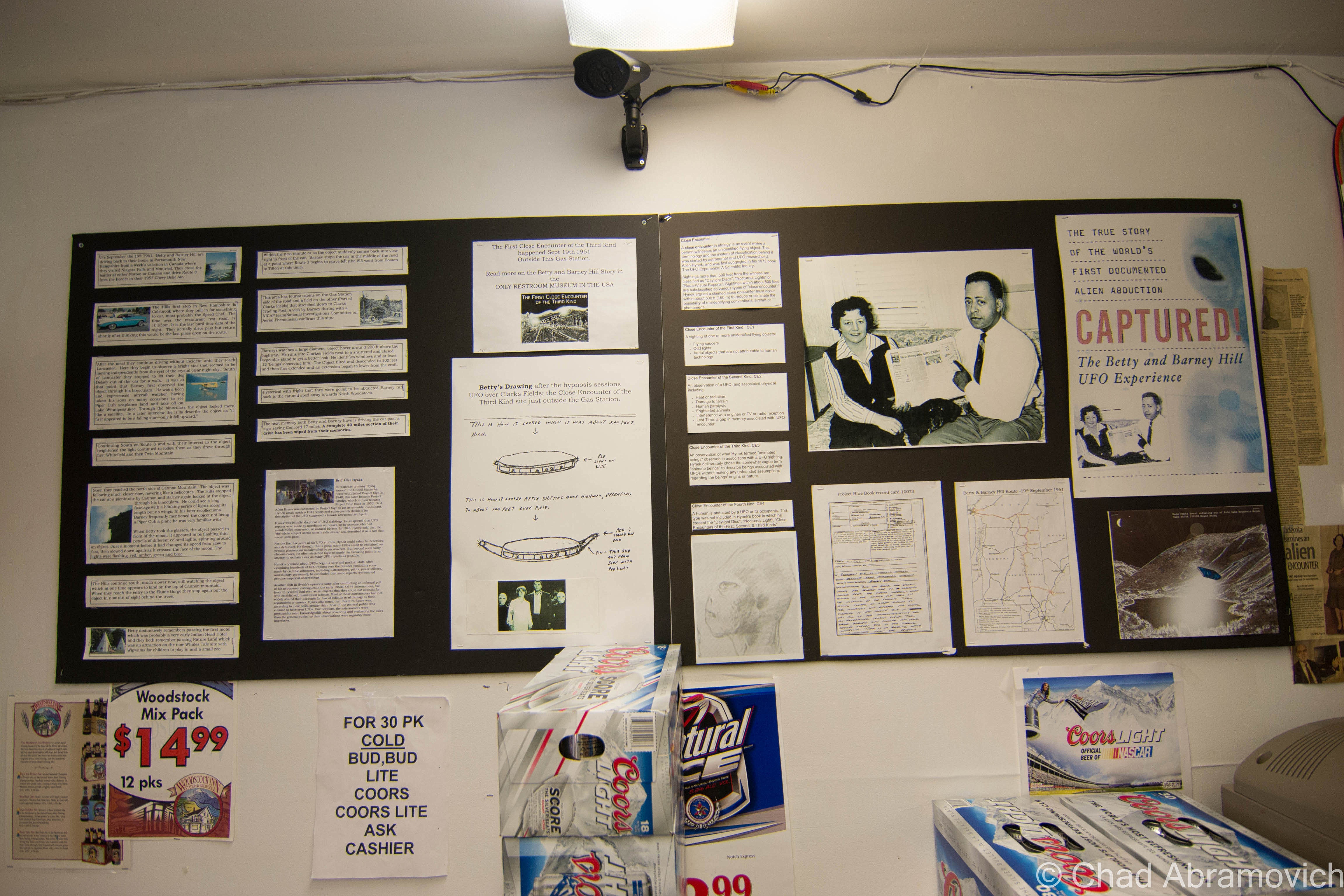

My amusement was carried from the wintery cold to inside the store, where I noticed the extraterrestrial theme continued in the form of wall to wall paraphernalia, photocopies of newspaper articles and other copied information related to both the Betty and Barney Hill case, other alleged incidents, and an assortment of fan images from science fiction TV shows and movies.

The shop owner who was behind the cash register at the time, caught me staring, and enthusiastically explained to me that right across the road from that exact store, was the actual site of the abduction. However, a friend of mine, as well as some commenters over Facebook, argued this fact, and said that it actually happened a further down the road, where Millbrook Road meets State Route 175 in Thornton.

Though I can really take or leave UFOlogy (more so on the leave side) I found this offbeat memorial and it’s fanaticism interesting enough to write about.

As the story goes, on the night of September 19, 1961, husband and wife Barney and Betty Hill were traveling South on Route 3 to their home in Portsmouth, NH, when, according to their claim, were followed by a spaceship near the present day Indian Head Resort, and eventually accosted by some sort of extraterrestrial crew, taken aboard their craft, examined, and then released on the side of Route 3 in the early morning hours of September 20 as the sun’s first rays would begin to grey the New Hampshire skies.

The collection I saw above me mounted on black poster board was originally smaller in size, and more of a quirky secret, formerly located on a wall inside their unisex bathroom. The current owner of the gas station has only owned the store for a few years now, and told me how disrespectful visitors kept stealing memorabilia and eventually, he grew sick of it and moved all of it around the store, so everyone could still enjoy it, but couldn’t grab a keepsake. As an extra precaution, they also outfitted the store with lots and lots of security cameras. They apparently get a lot of interested people who stop by, so they also sell alien key chains, bumper stickers, shirts and books about the Hills near the door. I neglected to buy a souvenir, but did get my coffee.

Have a weird encounter of your own? There is also a blackboard outside to the left of the mural, where you can share your own stories. I noticed that stuff had been written there, but nothing UFO related, which I suppose didn’t surprise me.

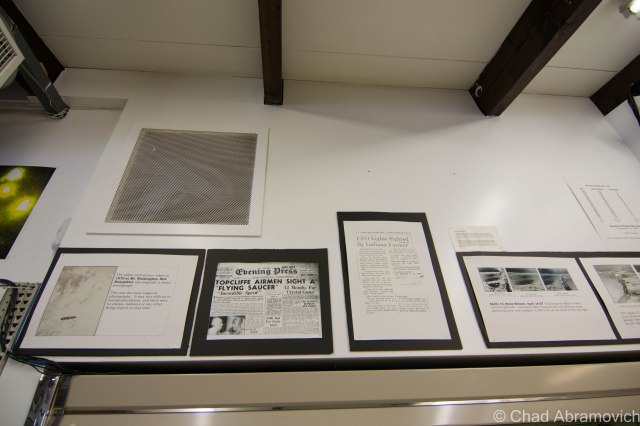

I didn’t think of this until after I had gotten back home and was writing up this post, but I have sort of a strange tie-in to all this. A location I explored last year reported seeing unidentified flying objects hovering above the skies shortly before Hill incident happened, but as for an actual connection between the two events, that remains subjective.

If you’re interested, just take Route 3 through Lincoln, New Hampshire, and look for the Irving Station near the Indian Head Resort.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my amazing fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations throughout the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4