There’s a gaping maw in the Berkshire Hills of Western Massachusetts that’s achieved a legendary degree for well over a century now due to its preternatural tales, mysteries, and tandem extraordinary and sinister creation that earned it the nickname “The Bloody Pit” (even though it’s a horizontal shaft) for killing hundreds of people who built it.

Its real name is The Hoosac Tunnel – an almost 5-mile long railroad tube that cuts underneath the Hoosac Range – a mountain chain that makes up the eastern rim of the jointed hill chains that make up the Berkshires region.

Skewed folklore tells that the name “Hoosac” roughly translates to “forbidden” in the language of the area’s first inhabitants – the Mohawks. But the actual meaning is akin to “stony place”, which is a pretty accurate description of the region. It’s also one of the many phonetic spellings of the word, which explains why New York, Vermont, and Massachusetts have the Hoosic River, the state of New York has the town of Hoosick Falls, and Vermont and Massachusetts share the Hoosac Mountain Range.

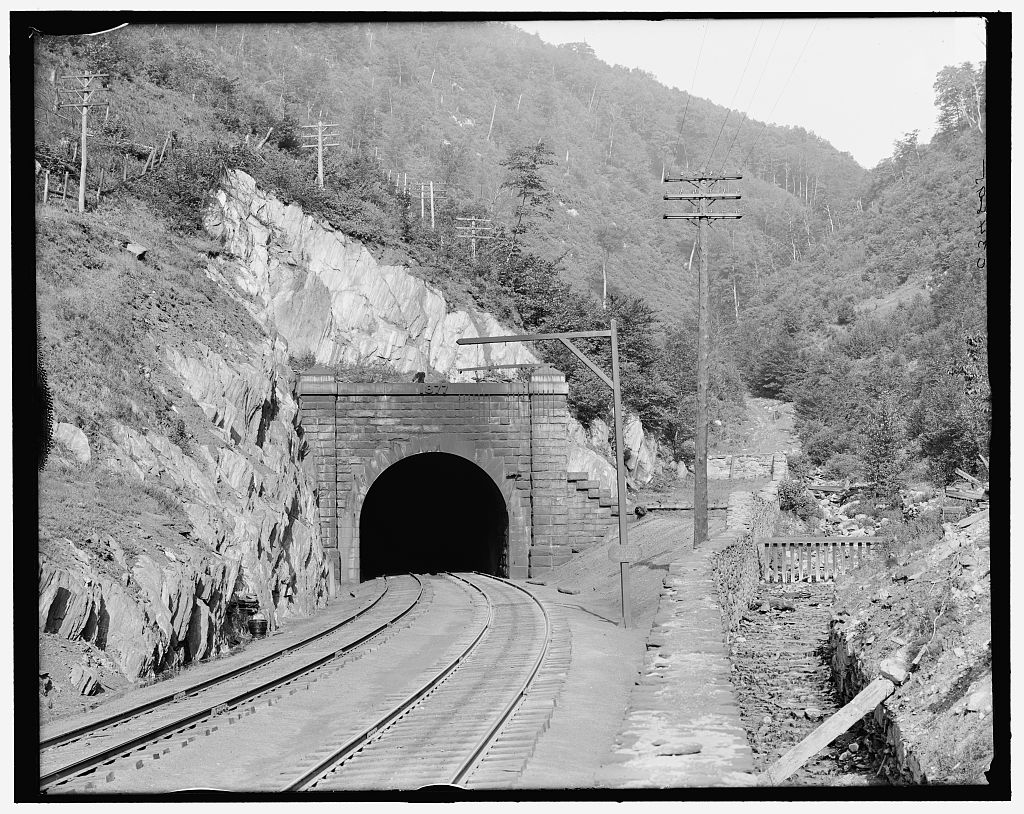

Every time I’ve stood in front of this imposing orifice that descends deep into the dark inscrutable heart of these hills, though, kinda brings the more ominous definition of its name right on home, and the vibes back up its designation as a damned place. It feels like you’re staring into an endless, ambiguous, and intimidating abyss that occasionally gurgles lonesome sounds and belches blasts of cold, acrid air in your face.

When this passageway was completed in 1873, it became a man-made leviathan turned celebrity – the longest tunnel of its kind in the world, a tangible example of an idea that had previously been thought to be impossible and foolhardy, and future-facing inspiration for other designs of engineering.

But it took lavish amounts of blood, tragedy, and time to make it happen. In its birth throes, the tunnel would devour an estimated 200 people, and for that reason, it became considered one of the most haunted places in all of New England, and that accolade is still very much stuck in the adhesive of the contemporaneous.

Why does something of this magnitude exist? Besides the fact that there’s something naturally settled within the psychological framework of humankind that makes us want to push anything that we consider a “boundary”, those pesky Berkshire Hills simply happened to be in the way.

Before the tunnel was built, you couldn’t really “get there from here” as us Vermonters like to say. Not at least without some substantial inconvenience.

As New England and New York’s Hudson Valley were beginning to enter the throes of the escalating industrialization in the mid-1800s – this huge disconnection was beginning to be felt.

A new railroad seemed like just the solution to intrepid self-made paper mill owner Alvah Crocker of Fitchburg, to extend the not completely altruistic gesture of financing the construction of a new railroad (not coincidentally, the railroad would also benefit his mills) – then cajoled groups of investors, engineers, and design firms to make it happen.

At the time, Massachusetts only had one railroad that accessed the western part of the state, and that ran through the southern part of the state, which left the north kinda isolated – both by the mountains and the fact that the railroad was cumbersome to access, and spur lines were billed exorbitant prices if they wanted to build a connection. Mr. Crocker wisely knew that a new, northern railroad would be incredibly serendipitous for him, and the rest of upper Massachusetts and Southern Vermont.

After survey work, the legend-crowded Deerfield River valley was chosen as the most practical route to veer westward on, until eventually having to puncture through what surveyors dubbed as the “thinnest” part of the unyielding slopes of the Hoosac Range – a chain of hills in the 2,000-foot elevations – to continue pursuing the trajectory all the way to Troy, New York – officially linking New York’s capital region and all their connections with Boston and inner New England.

To do that, they just needed to create a direct route through terra firma.

In 1842, Crocker and his cronies charted the Fitchburg Railroad that ran from Boston to Fitchburg, and then began to expand by acquiring smaller railroads and building new tracks to form a continuous link westward bound, the gestalt of which formed the Troy and Greenfield Railroad in 1848 as a connection – with the idea of the conceptualized Hoosac Tunnel being the cynosure of the project that would officially open up “the west” (or, anything west of the Berkshires).

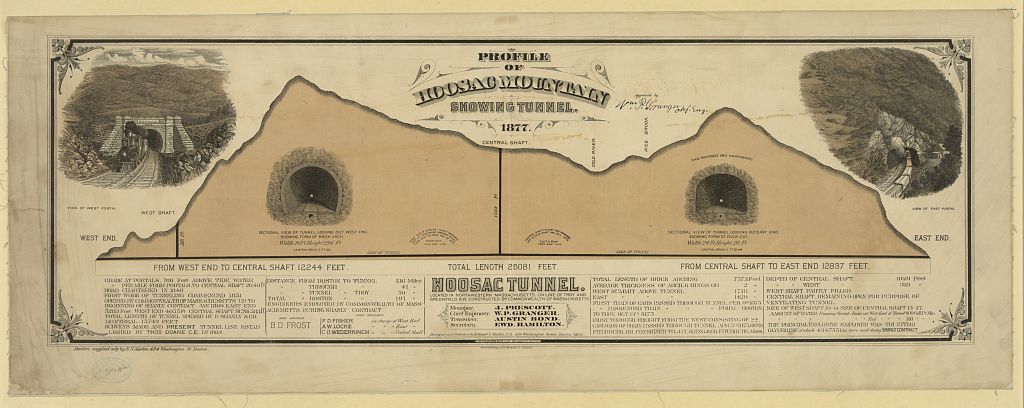

The scheme was to have 2 crews of laborers start digging at different ends of the mountains between North Adams in the west, and (the town of) Florida in the east, and eventually meet up in the middle.

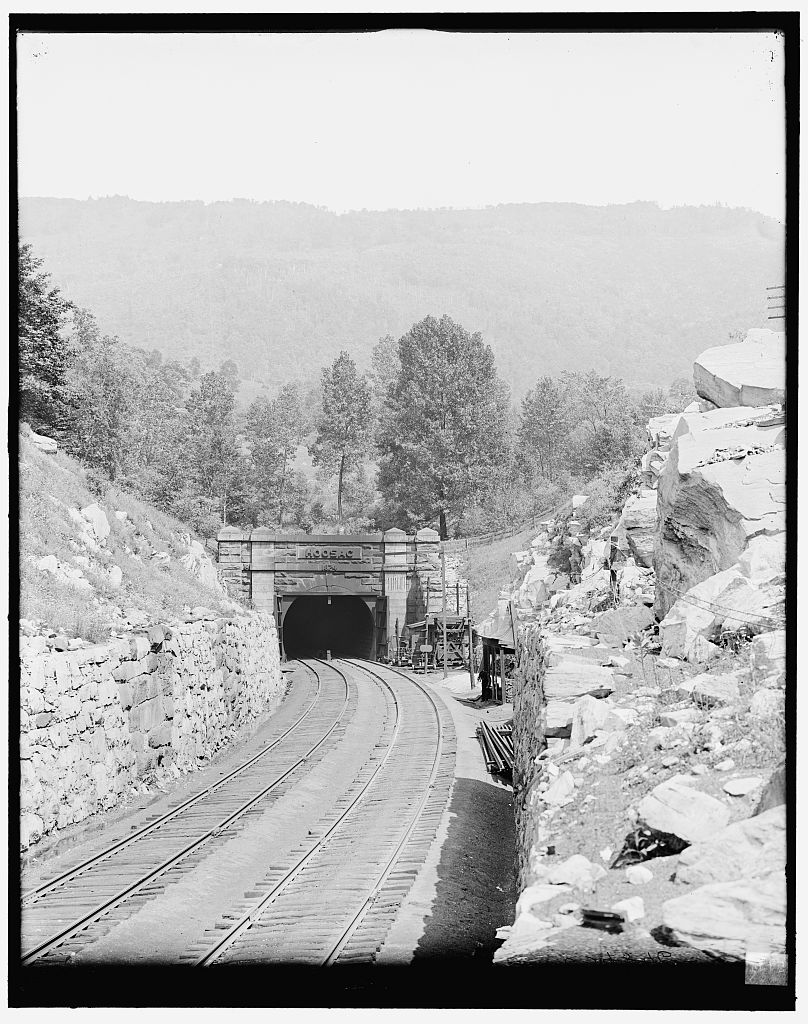

In January of 1851, ground was broken for the tunnel’s west portal on the mill town of North Adams’ side of the mountains, thus inaugurating Massachusetts’s original “big dig”.

But, such a colossal project couldn’t avoid being clingy to the sinister and was disturbed by bad luck from the very start.

In the summer of 1852, an innovative boring machine that was supposed to begin gouging out the tunnel’s eastern portal in Florida, got stuck in the Berkshire bedrock and nobody could extract it – so the crew had to start over in a new spot, with a new drill. If you know where to look, the original borehole that’s sometimes called “the false start” can still be detected in the woods today.

The tunnel’s clumsy start and continual ensuing setbacks ultimately became too expensive for Mr. Crocker, who eventually, begrudgingly had to declare bankruptcy. Other investors and engineers attempted to pick it up, but all would ultimately fail, and the project would stammer until the state of Massachusetts – who saw its prosperous potential – took it over in August of 1862.

In addition to the state declaring that most of the botched work done by private investors would ultimately have to be redone, including widening the tunnel and reinforcing it with bricks, some practicalities also had to be employed, or there was a sure chance that both burrowing crews wouldn’t link up!

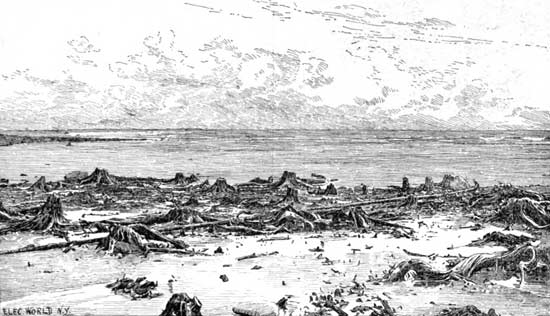

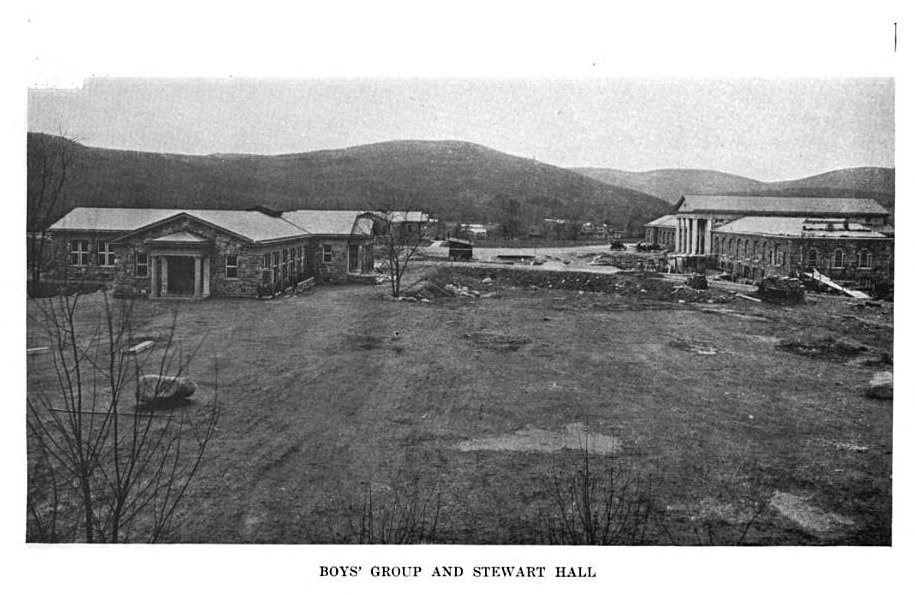

To make sure the tunnel-in-progress would turn into a tunnel-that-functions, 6 alignment towers were built over the planned path of the tunnel – 4 of them on the summits between the 2 digs and 2 at the entrances themselves.

The survey towers were simple constructions with stone foundations and a single-slant wooden roof. Each one was equipped with a transit scope (a device like a telescope) to make sure each tower aligned properly, and each had a red and white pole that protruded 25 feet up. Back then, the mountains had been cleared for farmland, so you would have been able to see one tower from another very clearly. Of the six that were built, the ruins of four can still be cooly detected in the mountains today!

Inside the tunnel, plumb bobs were driven into wooden plugs on the roof and hung from piano wire at intervals along the line that was sighted from the towers, and surveyors told the blasting crews which way to proceed.

And speaking of blasting crews, the Hoosac Tunnel was the first construction project to use nitroglycerin, but nobody was having a blast, because it directly accounted for a lot of the lives the tunnel would eat.

The endeavor would need so much nitroglycerin that a factory was built near the west portal to produce it. Over the years, I’ve heard intriguing but uncorroborated local hearsay that, though the factory is long gone, there are still several barrels of nitro that are lost somewhere in the Berkshire woods – and though I’m dubious, that delights me that the Berkshires still have wilds that things can still be hopelessly lost in, waiting to be found.

Because nitroglycerin was so new, most of the miners didn’t really know the dos and don’ts of working with the stuff, so a lot of accidental premature explosions happened, which either blew apart anyone in the vicinity, or pulverized them underneath mountain debris. Ironically, John Velsor, the new foreman at the nitroglycerin factory, was “blown to atoms”, as newspapers at the time put it – when around 800 pounds of the killer soup erupted in December of 1870. Not a single trace of the man’s body was ever found.

That certainly didn’t help anyone’s spirit, as the work had already been grueling from the very start. Crews were basically progressing a mere 2 feet a day. In the beginning, especially for the west portal activity, preliminary geological “surveys” saying that the rock was solid and sturdy were quickly proven wrong. What they were actually dealing with was what was called “porridge stone,” rock layers buckled into each other for thousands of years that were so saturated with water that they crumbled into something resembling quicksand. Miners complained that carving out the tunnel (especially the western portal) was like “building a sandcastle in the mud”. The highly unstable porous stone forced the builders to line a lengthy distance inwards from both portals with brick walls so that it wouldn’t collapse.

The west portal was so wet and unstable that a 264-foot tunnel had to be built around the portion of the western tunnel that had been completed to drain all the water that was flooding the worksite. Now known as The Haupt Tunnel, after the project’s first engineer – it still exists for those intrepid enough to search for it, and is pretty sketchy – with a few spelunkers running into spiders and narrowly avoiding a few collapses over the years.

Brinkman, Nash, and Kelley

On March 20th, 1865, explosives authority Ringo Kelley prematurely set off a blast that crushed his two companions, Ned Brinkman and Billy Nash, under untold tons of rock. Oddly, Mr. Kelley disappeared not long afterward without a trace. Did he run away? Had the guilt of killing two men become too much to bear? Or maybe it was because other workers started to report that they saw the angry ghosts of Misters Brinkman and Nash walking around within the pit? All anybody knew for sure, was that Mr. Kelley was gone.

Exactly one year later to the day, Ringo Kelley reappeared. Well, his corpse did. His body curiously turned up within the tunnel, precisely at the spot where Brinkman and Nash died, and he’d been strangled. Deputy Sheriff Charles E. Gibson investigated and determined that Kelley’s death had occurred between midnight and 3 a.m. of the day that he was discovered. But no clues were ever found, and no suspect was ever identified.

I can’t even imagine the vigor that those guys must have had to muster and keep stoked just to face a day at work. Most of them needed the work too badly to quit, but, some of them couldn’t take it and walked off the job – either because of the dreadful conditions, or now, because there were whispers of the tunnel being haunted and people seeing strange specters within the dark passage that they thought to be the shades of their fellow deceased miners.

Soon, the Hoosac Tunnel project was being christened as “The Bloody Pit”, a nickname that the tunnel has never been able to get rid of. And its nickname-legitimacy-card would be pushed when the project’s worst calamity took place while digging its central shaft.

The Central Shaft

With a tunnel almost 5 miles long, ventilation was needed, or there’d be plenty of unfavorable predicaments, and the resolution was as astonishing as the tunnel itself.

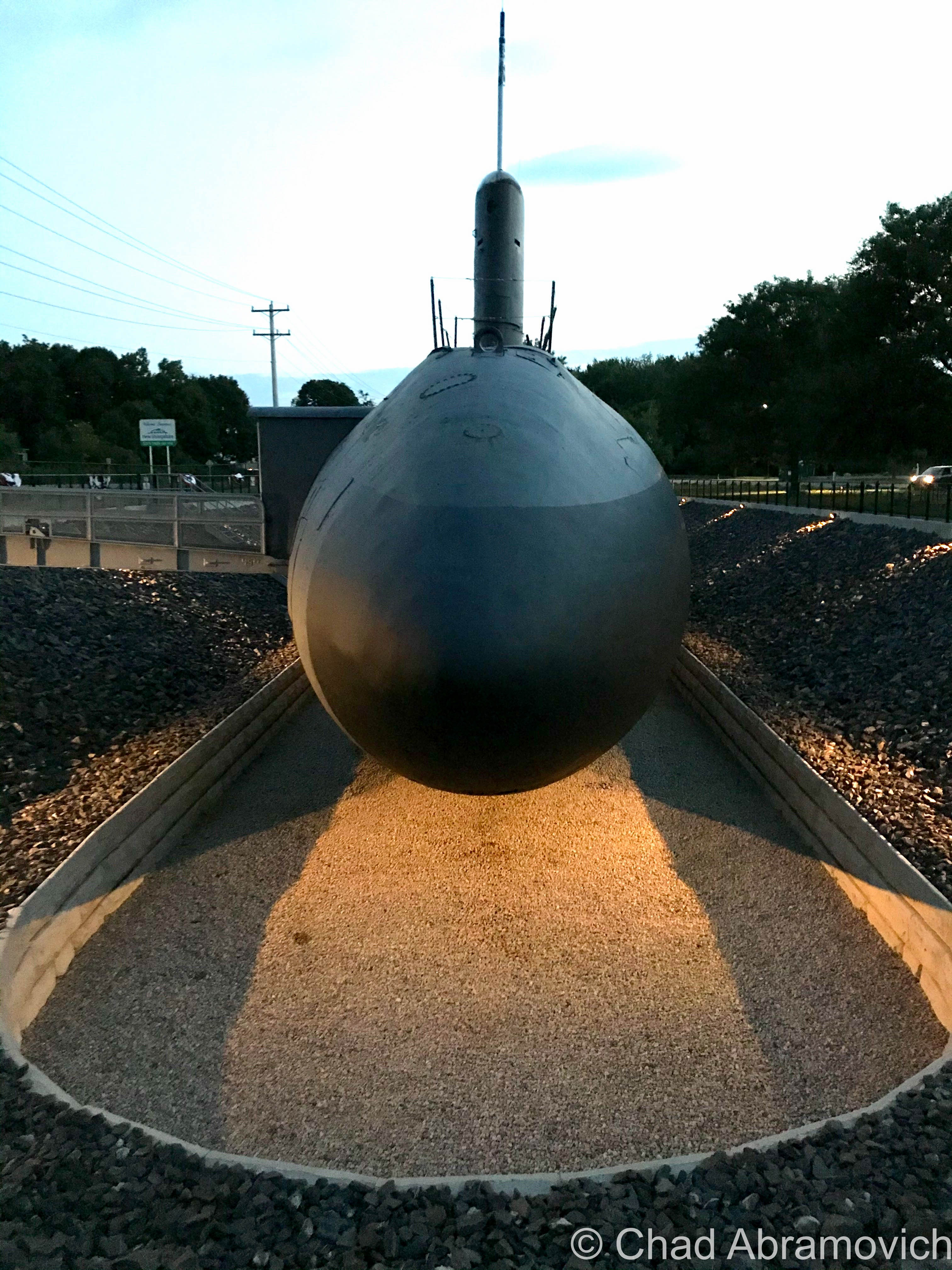

The Central Shaft is a 1,028-foot vertical conduit through Hoosac Mountain – essentially a giant hole that would be dug from the top of the mountain all the way to the tunnel below. The shaft would mark the tunnel’s close-enough halfway point (the actual mid-point was too close to the Cold River for a safe dig), and once it was completed, provide it with ventilation. The opening would also become the fastest way to introduce laborers into the tunnel – by dropping them down in a giant bucket instead of them having to walk about two and a half miles.

On October 17th, 1867, crews had completed boring about half of the central shaft.

Thirteen men had been dropped in the pit and working away, when sneaky escaping fumes from a naphtha fueled lamp in the hoist house above, somehow ignited, obliterating the structure. A deadly rain of freshly sharpened drill bits and tools fell down upon the trapped men, followed by the winching machinery, and finally, the flaming debris of the hoist house itself. If that wasn’t bad enough for the hapless crew, the air and water pumps stopped working almost immediately, leaving them stranded without oxygen as the shaft started to fill with water.

Helpless onlookers realized that nothing could be done, except for speculating whether the men who survived the falling debris would either die of suffocation or drowning.

When the smoke had finally cleared a little after 3 A.M., a miner by the name of Mallory volunteered to be lowered down on a rope to investigate and was given 3 oil lanterns for perceptibility. He was eventually pulled back up when 2 out of the 3 lanterns were snuffed out by lingering noxious gasses. Once above, he barely gasped out the words “no hope”, and then fell unconscious.

The flooded shaft was covered up and left untouched for about a year. Maybe it was partially because people in the vicinity claimed that they started seeing indistinct, fleeting shapes that’d be lurking one moment, and fading into the Berkshire inclines the next. Muffled disembodied groans and cries could also disturbingly be heard, almost like they were spooling out from within the earth itself.

But, the central shaft needed to be completed, so a year later, it was finally drained of water, and the bodies of those that perished down there were finally exhumed. That was when a chilling discovery was made; a raft was found.

Those that survived the initial ordeal had crudely taken a futile stab at survival – eventually dying of asphyxiation or starvation as the world above deemed them as already dead. Interestingly enough, those strange visitations and visions that haunted the domain prior, seemed to vanish afterward.

On August, 13th, 1870, the Central Shaft was ready to start central shafting, when it finally broke through the mountain and connected with the tunnel below.

Hoosac’s Horrors

But by now, the Hoosac Tunnel project morphed into the well-tread beat of other arcane phantoms that seemed to treat the tunnel as a manifesting mecca, and the formula seemed to be when one group of shades decides to split, others get ready to turn up the tomfoolery. And as early as the 1870s, the gristly phenomena was starting to attract early ghostbusters – an allure that has never faded.

One of the first was a Dr. Clifford J. Owens, who on the night of June 25, 1872, took an expedition into the tunnel accompanied by drilling superintendent James McKinstrey. What the two men witnessed was reported in detail in Carl R. Bryon’s book A Pinprick of Light:

“We had traveled about two miles into the shaft when we halted to rest. Except for the dim, smoky light cast by our lamps, the place was as cold and dark as a tomb… Suddenly I heard a strange mournful sound. The next thing I saw was a dim light coming from… a westerly direction. At first, I believed it was a workman with a lantern. Yet, as the light drew closer, it took on a strange blue color and… the form of a human being without a head. The light seemed to be floating along about a foot or two above the tunnel floor… The headless form came so close that I could have reached out and touched it, but I was too terrified to move.”

The apparition remained motionless in front of them as if it was looking at them just as they were of it, before floating toward the west end of the tunnel and vanished.

In October 1874, Frank Webster went missing when hunting near the tunnel. When searchers found him in the woods days later, he was in shock. He confessed that he had heard weird voices – their macabre siren song had coaxed him to enter the tunnel. He went in, and saw ghostly figures milling about that took his hunting rifle and beat him with it! He had the scars to prove it, but no rifle.

The next year, Harlan Mulvaney, an employee of the Boston & Maine Railroad, was supposed to deliver a cartload of wood nearby, but instead, fled in an unexplained panic and was never heard from again.

Despite all of these sinister happenings, eventually, both digging crews eventually met up in the middle of the mountain, and were less than an inch off! The plan had worked!

A New Marvel

It’s hard to imagine that simultaneously digging at both ends of a mountain over two thousand feet in elevation for twenty-two years and meeting in the middle using only plumb bobs and piano wire as a compass, would create what became America’s longest tunnel, a landmark in hard rock tunneling, and a new world wonder. The Hoosac Tunnel also laid down the rules of construction for practically all subsequent tunnels, and that’s still true today. I wonder if Mr. Crocker ever imagined that his hubris and attempted resolve would wind up being that impactful?

At almost five miles long, twenty-four feet wide, and twenty feet tall, using twenty million bricks to keep it together, it cost over $21 million, which was about ten times the initial price estimate. It would also cost an estimated 200 lives, with some saying that number is as high as 300.

The tunnel’s headings (both respective routes from each side) were purposely inclined by 26 feet per mile – with both slopes meeting up at an elevated mid-point so all the water that puddles inside (there’s a lot) is drained out through both portals, but it also prevents you from seeing one end from the other end, making the passage seem endless – peering in, you only see blackness.

On February 9th, 1875, the remarkable Hoosac Tunnel was ready for its first train, and it became a big deal basically from the get-go, becoming both a cog in the regional economic engine, a tourist attraction, and a memento for some patriotic flexing.

The Tunnel Today

In the coming years, more improvements and features would be added. The tunnel originally had a double set of tracks running through it, because of the enormous amount of trains that were utilizing the American rail network in its prime. And all of those locomotives were powered by coal – which belched an awful lot of noxious smog as a tradeoff, which was making the tunnel a pretty hazardous environment, regardless of the central shaft’s existence. Seriously. Some people were actually succumbing to asphyxiation on trips through the tunnel. So in 1911, electricity was brought in to power a fan atop the central shaft to help pull the fumes out. But even that wasn’t completely eliminating the problem, so briefly, the tunnel went electric, and trains had to stop before entering and then be pulled through via electric cables. In 1946, a double fan system was installed at the top of the central shaft, which are the same ones in use today.

Directly below the central shaft, a room was blasted out of the mountain rock and became a shanty for trackwalkers and work crews, and inadvertently, it also became a frequent haunt for hobos – which earned the chamber the affectionate nickname “The Hoosac Hotel”, or sometimes “The Hoosac Hilton” – both of them still enthusiastically used in tunnel-talk today. I’ve also heard the possibility of there being some of the now-iconic “hobo graffiti” – a pictorial-based clandestine communication system invented by savvy recalcitrant turn of the last century train hoppers and vagabonds, scrawled somewhere within the room, but so far I haven’t seen the evidence.

The Hoosac Hotel has a real creepy vibe to it, and that might be influenced by the fact it’s in the same spot that a large section of tunnel collapsed and killed a bunch of workers, and some say it’s also where misters Brinkman and Nash were discombobulated by an explosion. Nearby is said to be the legendary secret room(s), walled up to contain some awesome horrors.

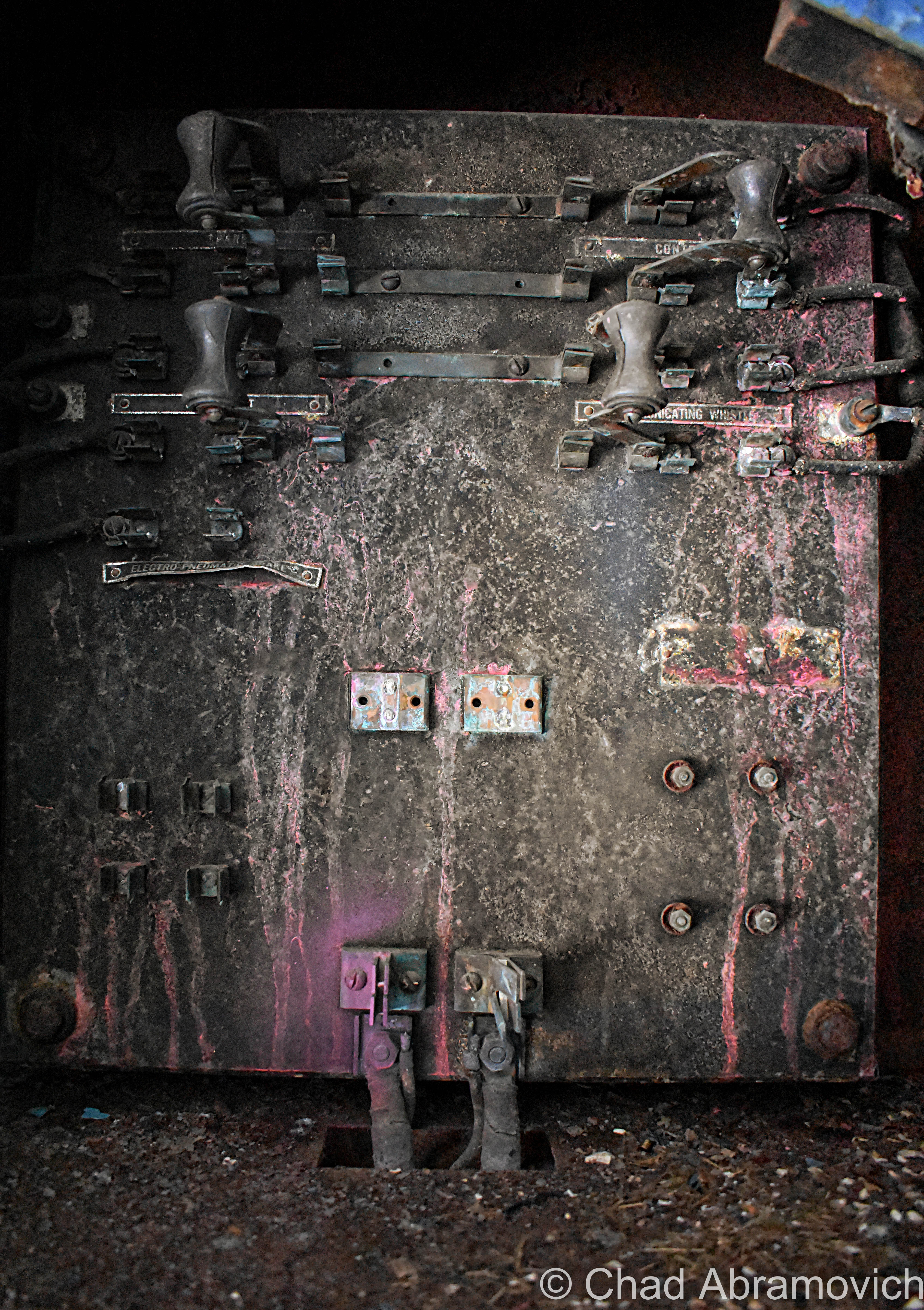

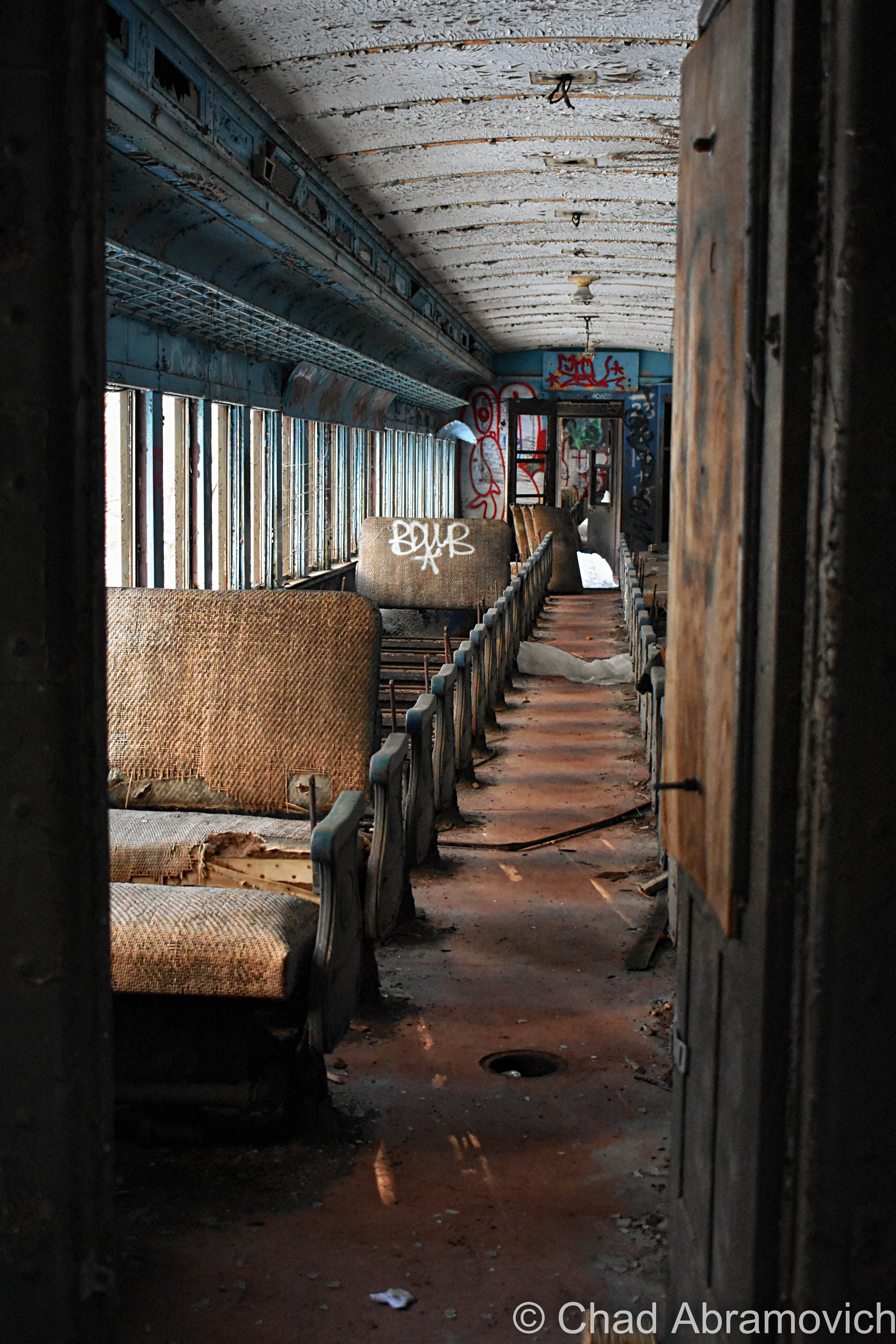

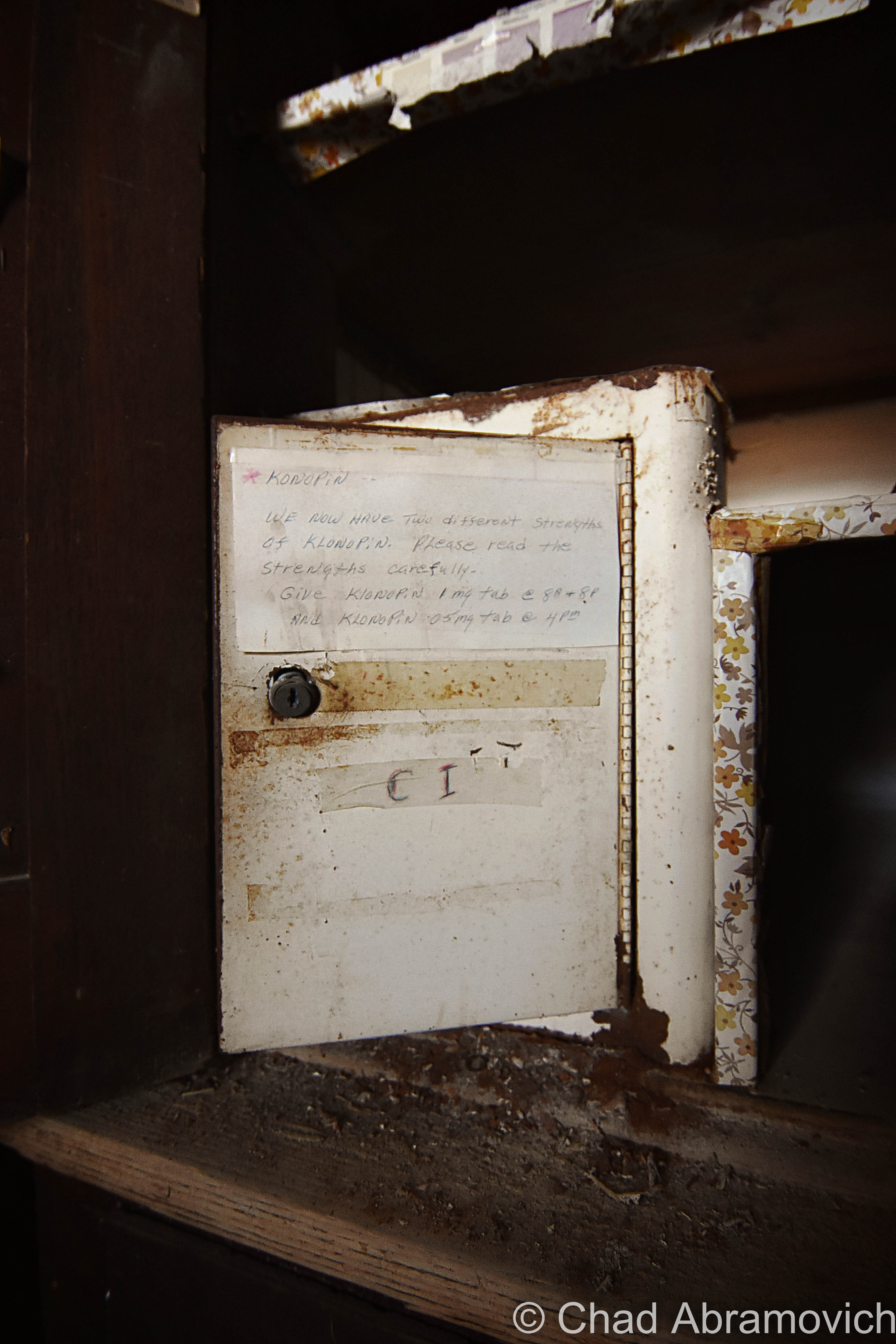

It’s also the physical characteristics that alter the mood. The room is separated by the tracks with a wall of sordid century-old bricks that have a dark patina with age and all the pollutants that used to hang around within the tunnel – the ceilings are the natural mountain rock that constantly dribbles with water. Even with flashlights, the darkness practically ruins the light, but you can still make out the forsaken relics within; an old wooden desk, chair, and dented archaic communication and control equipment – all slimy and glistening because of the dampness. Modern relics like Twisted Tea cans and Slim Jim wrappers strewn on the ground alert you that you’re not the first one to venture this far into the tunnel, even though you really start to inwardly feel that you’re a whole world away once you’re that far in. I’m sad to say that my photos of this room that I took back in 2012 have been lost since then, so I’m gonna have to make another trip in to get some more photos up on this blog.

More sinister urban legends told of bodies wrapped in black trash bags found in the creepy room. Other yarns tell of other secret rooms built both somewhere in the tunnel and up in the central shaft that had been curiously bricked up. Some people say these spaces contain some unspeakable horrors that are best left undisturbed… (Check out this cool video below. These badasses not only explore the Hoosac Hotel, but they actually repel up the central shaft from inside the tunnel!)

The incredible Moffat Tunnel in Colorado took the accolade of the longest manmade tunnel in the western hemisphere in 1916 – at 6.2 miles underneath the Rockies! Then Washington’s 7.8 mile Cascade Tunnel became the longest in 1929, and currently, the Rogers Pass tunnel in British Columbia at 9.1 miles holds the record. But the Hoosac Tunnel basically wrote the manual on modern-day tunnel building, and all of these latter construction projects were successful because of what was learned while building it.

The American Society of Civil Engineers made the tunnel a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1975, and it remains the longest in-use railroad tunnel east of the Rocky Mountains, and though it’s basically more of a curiosity nowadays, us New Englanders still love/fear the Hoosac pretty affectionately, and dark tales are still told…

In 1973, Bernard Hastaba was in the mood for an adventure and decided to walk the entire tunnel. He entered via the North Adams side, and never re-emerged. He wasn’t found inside, he wasn’t found at all. He had, apparently, vanished entirely.

In 1984, a professor and hobbyist ghost hunter named Ali Allmaker was gripped with the uncomfortable sensation of someone, or something, standing next to her. She described whatever it was as walking right behind her, and feared that it would try to grab her and pull her into some unknown, awful horror. Maybe Mr. Hastaba encountered the same situation on his walk through the tunnel, but wasn’t as fortunate…

There are still modern-day accounts of weirdness, mayhem, and paranormal pandemonium in and around the tunnel today, and that’ll probably continue to be the trend.

Strange winds, wily apparitions, disembodied voices both caught on tape recorders and heard in real-time, and odd illuminations like balls of blue-ish lights, and a more railroad-centric phenomenon that’s also spotted around the country; spook lights. Given the Hoosac’s pedigree, I’d honestly be pretty disappointed if spook lights didn’t give an appearance here. “Ghost hands” have also been known to both push people in front of moving trains and pull them back out of harm’s way. It just depends on the day I guess?

As for its mortal caretakers, Pan Am Railways owns the passageway now, and it looks like they do a kinda lousy job at maintaining it, which is tragic. The West Portal’s snow door was added in 1954 – which is basically a big steel garage door installed after a locomotive derailed due to ice on the rails inside, that help keep snow and other nasty weather out of the structure and has become a defining feature of the west portal.

Originally 2 sets of tracks ran through the tunnel, but it’s been down to a single track since 1957 when tractor-trailers and the interstates became the leading mode to move. The last passenger train went through in 1958.

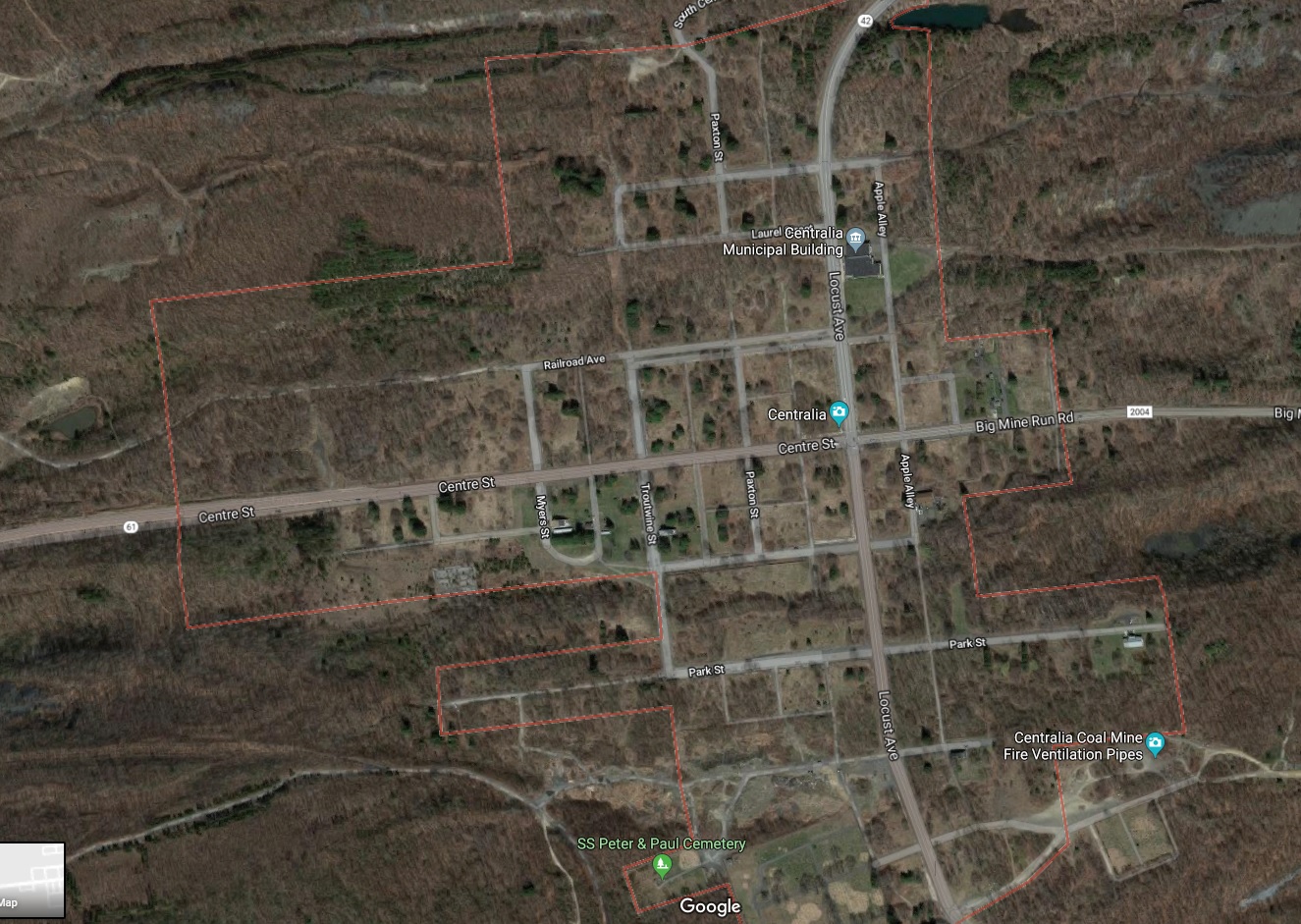

Around 8 freight trains a day are now all that run through its lonely void – and some of them are called “truck trains”, which can be as up to three miles in length and help reduce some of the traffic on the bay state’s byways. Structural engineers have been analyzing the tunnel since the end of the 20th century to see about renovating it so double-stacked container freight trains could pass through it – the track grade elevations were even dropped in 1997 to allow more clearance and taller railcars, but ultimately, the cost was deemed too high, and not imperative enough because there’s already a suitable route through southern Massachusetts, which I suppose is a bit ironic.

It’s kinda sad that it isn’t used more, given just how much effort went into creating it, and realizing that there was a time when a few National Guard soldiers would actually be stationed at both entrances during times of war to prevent potential terrorist attacks on it.

In early 2020, there was a substantial collapse about 300 feet into the more vulnerable western heading that shut the tunnel down for a few months, caused by both general wear and tear, and water flowing in from above the tunnel that was being trapped in blocked drainage tunnels that were supposed to be being maintained, which created a sinkhole that dropped about a 150 feet of mountain onto the tracks and opened up a cavity in the slope above. A structure this old, and this “constantly getting fisticuffs from the environment” is practically guaranteed to need some fixin’ up as the years pass by, but I really hope the Hoosac Tunnel doesn’t become the Hoosuck Tunnel. I really outdid myself with that last sentence.

But seriously, though, it’s such a special and uniquely New England landmark that’s left an epic indelible impression on our rhapsodized region. It would be a huge shame for it to diminish. Oh, and a literal topographical catastrophe.

Berkshire ODDysey

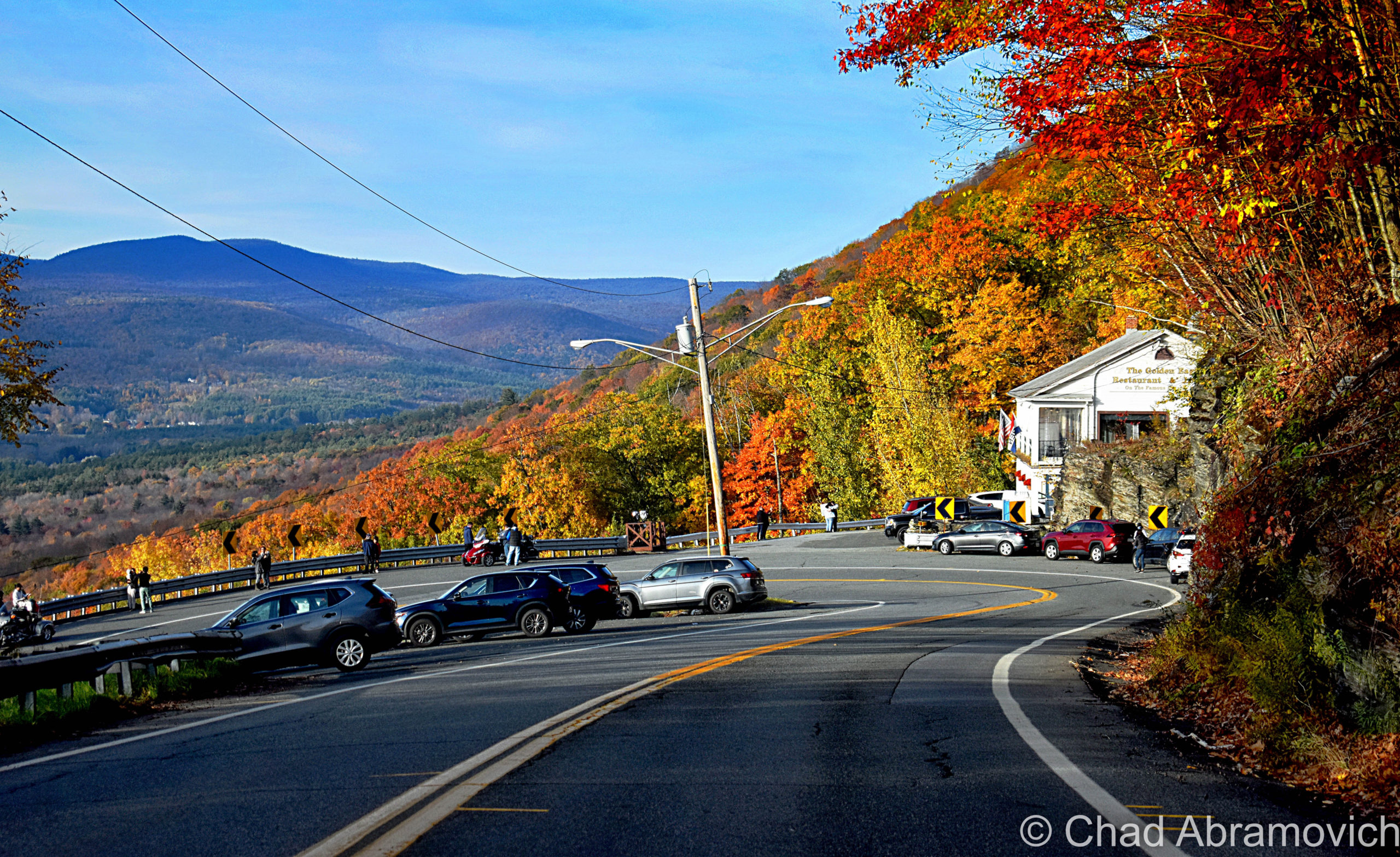

It was the week of Halloween, and I and a few friends took a jaunt down to the Berkshires to see some oddity and see some foliage, and were listening to the podcast Lore to rev up the creepy vibe. It was also one of the loveliest fall days I’ve ever encountered!

The Berkshires are actually an extension of Vermont’s Green Mountains that have a reputation of their own, so I figured I oughta do more exploring around their nooks and crannies seeing how I live so close. Usually, we’d hit up the old racetrack in Pownal if we were heading down that way.

It’s pretty amazing how much the landscape changes once you cross the Massachusetts state line – It basically immediately gets kinda suburban-y and billboard-y, and this is supposed to be one of Massachusett’s most “rural” areas. Even a good chunk of Berkshire backroads are paved and feel like you’re really in a suburban fringe community than actually in the mountains. But then again, Vermont is a bizarre bubble, and it’s only until Vermonters begin to venture outside our state lines that we recognize this.

We drove through the neat historic mill turned liberal arts burb of North Adams, a town that the Hoosac Tunnel fundamentally ensured would thrive. The tunnel is even on their town seal that declaratorily exclaims “we hold the great western gateway”, which as far as civic iconography goes, is pretty rad.

3,489 foot Mount Greylock – the tallest height in Massachusetts and named after a legendary Abenaki chief – loomed over the wobbly rows of old mill tenement houses that bracketed the main drag. Greylock is a mountain with some cool footnotes hidden up its non-existent sleeve. The only taiga-boreal forest in the state survives upon its slopes, and a unique natural feature called “The Hopper”, a glacial cirque (a natural amphitheater-shaped valley) has been declared a National Natural Landmark. An asphalted scenic seasonal road curves its way up to the summit, and it always reminds me of an inactive blog post I read years ago about some young guys who decided to literally race the sun. They embarked in the dark at the top of Mount Greylock and tried to see if they could hightail it to Cadillac Mountain in Maine’s Acadia National Park – the first place the sun rises in the United States – to catch it happen. Sounds fun to me!

We linked onto the famous Mohawk Trail in North Adams, which in itself was an adventure! The Mohawk Trail is the affectionate and designated byway name for MA State Route 2. The name came from the fact that the road tar you’re driving on top of was put over what used to be a literal Mohawk Trail – a vital path that connected The Hudson River to the Connecticut River via going up and down the Berkshire Hills that was originally used by the local Mohawks and other area First Nation clans like the Mahicans, for trade, hunting, travel, and warring their enemies.

The Mohawk Trail basically invented and then literally paved the way for the idea of the American road trip, long before iconoclasts like Route 66. It got its start in 1914 when the state dished out money to improve the road around the dawn of the automobile craze. Early strategizing automobile clubs started to peddle the road as a tourist attraction to bring some cash into western Massachusetts, and it worked so well that it planted the seeds for Americans seeking out particular roads to drive for pleasure. It’s still on my bucket list to drive the whole thing!

But, this scenic route wouldn’t be very scenic anymore with over-development, so foresighted conservationists before there were really conservationists started zoning and limiting development along the roadside, to keep one of the wildest parts of Massachusetts wild. The commonwealth acquired 5,000 acres of mountain slopes and created the Mohawk Trail State Forest in the 1920s, and during the Great Depression, the CCC came to the area and spruced it up by building roads, primitive campgrounds, and cabins up along miles of serpentine hill climbs. The tallest tree in all of New England – a 168-foot white pine named Jake Swamp – as well as about 700 acres of extremely rare old-growth forest with some trees over 400 years old – are somewhere within the state forest.

And then there’s the wicked hairy hairpin turn on the side of a mountain on the Clarksburg/North Adams town line, one of the more distinguished and (in)famous sections of the trail.

At the top of the Hoosac Range, you’ll enter the town of Florida, marked by one of Massachusetts’s iconic book-shaped town line signs, and is the total opposite of what we think of when we hear the word Florida. It’s the highest town in elevation in the commonwealth, and allegedly gets more snowfall and colder temperatures than any other town in Massachusetts. The name, too, is kind of a mystery. Even the town’s website gets shoulder shruggy at how the name was chosen. It is possible that the name was an invented one, bandwagoning on a trend in New England around the 1800s where remote, mountainous towns with poor farmland were given ‘exotic’ or pleasant names to lure settlers there.

Florida is also the gateway to the Hoosac Tunnel’s eastern portal, which is the easiest of the two to see. From the Mohawk Trail, we went from the top of the Hoosac Range to the bottom and drove through an uncanny valley where New England’s perennial death was some of the most glorious I’ve ever seen – before we saw the giant hole in the mountain that told us we were there.

“The great bore” was everything but a bore! Standing at the foot of its wickedness was awe-inspiring and intimidating.

Cold, sour air belched from the murk and cryptic sounds echoed and cursed from within. Icy groundwater salivated from the ceiling and pooled along the tracks. Pieces of century-and-a-half-year-old brickwork occasionally crashed down with lethal strikes.

On a white-hot summer day back in 2012, I explored about half the length of the tunnel with a good college buddy of mine. I remember measuring that trip as such a big deal for me, because it was my first oddity expedition outside of Vermont, around the time when I was really struggling to find my identity and my beat out in the universe, and just beginning to try my prowess at blogging.

The tunnel was a tourist attraction even then, which was evident when an assembly of Hell’s Angels rumbled up next to us and decided to join us on our foray into the transport tube’s east portal. Well, at least that’s who they proclaimed to be. Some of those guys looked like they could do some casual origami with a parking meter, so I didn’t feel up for fact-checking them.

Leaving the Berkshire heat, the clammy darkness swallowed us and gave us a lot to stumble on. Endlessly falling water formed rivulets along both sides of the tracks, clogged with silt, gravel, brick shards, and sporadic live electrical cables. The tracks faired no better for a less accident-prone passage – the wooden railroad ties were warped, in various stages of deterioration and glistened with wetness, and made anything that wasn’t a slow and steady walk not such a great idea, unless a rolled ankle won’t throw off your mojo. I’m not in that camp of people.

We were about five minutes into the tunnel and the wife of one of the bikers had some kind of a happening. She immediately stopped in her tracks on the tracks, and explained she had the ability to detect when ‘spirits’ were in proximity. Not only were there apparently hoards of them in the tunnel, but according to her, they wanted us out. So she and the rest of the Hells’ Angels vamoosed, and me and my friend decided to continue onwards to the Hoosac Hotel.

I was far more concerned about running into a freight train than a ghost, and the fact that, even if I press myself up against the grimy tunnel walls, I barely have a few inches of space between me and the whizzing side of the locomotive to prevent me from being smashed. They pass through at random hours, spew potentially lethal amounts of diesel fuel, and the racket is enough to potentially cause some hearing damage, if not complete deafness.

Water was everywhere, seeping out of the ceiling and raining down our necks and soaking our boots. Bricks crashed down to the earth erratically. We were far enough in the tunnel where the daylight coming in from the east portal could no longer be seen – it was just a sullen lacuna, and the silence was so intense, my tinnitus buzzed through the strange isolation like crazy. It was gritty, dirty, and cold.

Then, I saw something far ahead in the distance, that today I’m still uncertain was paranormal or not. Within the ghastly illumination of a lone crimson tunnel light affixed to the natural rock wall, I saw a startling silhouette of what appeared to be a man. I abruptly stopped my progress forward, motioned to my friend, and uttered something along the lines of “Fuck, we’re busted”.

I wasn’t thinking it was one of the tunnel’s many shades, I thought it was an actual railroad employee that was gonna bring the law down on our trespassing butts. Motionless, we stood in place, and I stared at this figure, trying to understand what I was seeing. Its outline appeared to be dressed up in clothes that I regarded as “official-looking”, like an old-fashioned uniform, which further backed up my fear that it was some kind of authority figure that was making haste towards us. But that was when I noticed, that no matter how long we were watching it, and despite the fact that the strange man looked like it was practically power walking in our direction with determination, it strangely never seemed to gain any ground – it just kept on walking but never making any progress.

Then, we saw another light and another figure. This new sight, however, was definitely making progress in coming our way. It was a train. My friend and I booked it and clumsily sprinted back towards the safety of the east portal as fast as we could, as we stumbled and slipped over slippery tracks and adjacent inundated burms. We made it out just in time as a lengthy locomotive came barreling out behind us – grimmy, wet, and desperately trying to chase a little breath. To this day, I’m not sure exactly what was hustling towards us in that tunnel. Maybe we should have listened to biker wife lady?

In the fall of 2020, me and some other friends decided to take a jaunt down to the Berkshires to revisit the tunnel, and to get a little relief from the stresses of the pandemic, and we had a lot of fun. It was around the close of the evening by the time we had arrived, and the tunnel was crowded with obnoxious social media influencers and TikTokers, but it was engaging to see it again – you never really tire with a site like this one.

Next time I head back, I’d like to finally make it to the Hoosac Hotel and get some pictures to share with y’all on this blog post!

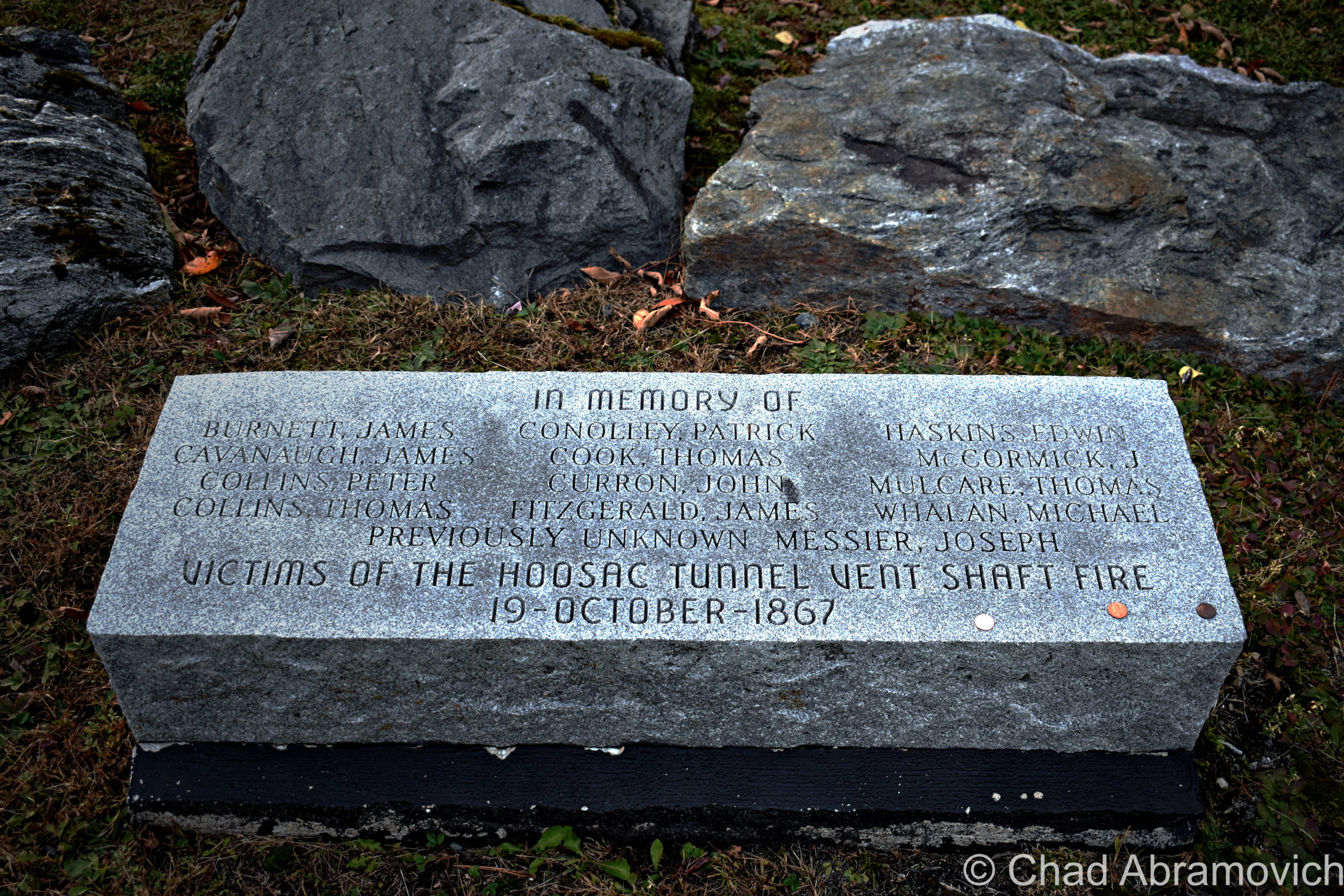

Before we headed back to Vermont, we took a quick drive down aptly named Central Shaft Road, to the top of the central shaft to check out the fan units, and to see a relatively new memorial that’s been dedicated to all the lives that the tunnel has reaped – a squat and prostrate rectangular block of granite laid down near some old apple trees across from the fan. Unbeknownst to us, we actually wound up visiting on the same day of the central shaft catastrophe.

Here’s an older video of the fans in action – to get an idea of just how noisy they are!

I also haven’t had an opportunity to visit the west portal yet, so that’s still on my Hoosac-centric agenda. The last time I was down that way, it was a bit after the collapse. While the east portal is easy to access off a paved road, the west portal is obscured from a relatively well-traveled throughway – at the end of a dirt access road, which was gated and decked out with a few new looking “no trespassing” signs, and I totally I didn’t want to run into disgruntled railroad employees who were doing some collapse-cleanup.

This was a real fun explore, and even more fun to research and unpack everything I was gleaning about this place. The most fascinating thing about a place like the Hoosac Tunnel, is that it dutifully keeps spawning new tales, tall or true, and most likely will for posterity.

———————————————————————————————–

Do you have a spooky story from your trip to the tunnel that you’d like to share, or maybe have appear on this blog entry? Or perhaps you wanna make me hip to another Berkshire oddity or abandonment? Email me please!

Links

The closest thing the tunnel has to an ‘official’ website, which goes into amazing detail on all portions of the tunnel: HoosacTunnel.net

http://paulwmarino.org/hoosac-tunnel.html – a fantastically researched resource, with tons of historical imagery!

https://mysterious-hills.blogspot.com/ – my favorite Berkshires blog! Joe puts a lot of thought into his entries and is a great storyteller!

Here’s a video that actually films a modern-day train ride through the entire tunnel – it’s a neat watch and a good dose of perspective!

Since 2012, I’ve been seeking out venerable examples of Vermont weirdness, whether that be traveling around the state or taking to my internet connection and digging up forsaken places, oddities, esoterica, and unique natural features. And along the way, I’ve been sharing it with you on my website, Obscure Vermont. This is what keeps my spirit inspired.

I never expected Obscure Vermont to get as much appreciation and fanfare as it’s getting, and I’m truly grateful and humbled. Especially in recent years, where I’ve gained the opportunity to interact with and befriend more oddity lovers and outside the box thinkers around Vermont and New England. As Obscure Vermont has grown, I’ve been growing with it, and the developing attention is keeping me earnest and pushing me harder to be more introspective and going further into seeking out the strange.

I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to keep this blog going. Obscure Vermont is funded almost entirely by generous donations. Expenses range from hosting fees to keep the blog live, investing in research materials, travel expenses and the required planning, and updating/maintaining vital tools such as my camera and my computer. I really pride and push myself to try to put out the best of what I’m able to create, and I gauge it by only posting stuff that I personally would want to see on the glow of my computer screen.

I want to continuously diversify how I write and the odd things I write about. Your patronage would greatly help me continue bringing you cool and unusual content and keep me doing what I love!