Abandoned roads have a story to tell. They represent abandoned dreams and ambitious projects that reflect the growth and often tumultuousness of our society, or the irresponsibility of our governments, cracked asphalt scars that mar the landscape and are reincarnated into monuments of failure.

The Southern Connector

There is a stretch of abandoned interstate highway in Burlington’s south end, crumbling to pieces as the urban development around it was designed purposely to obscure the fact the blighted stretch of pavement even exists, with privacy fences and shrubbery. If you’ve approached town via exit 13 or have driven on the southern section of Pine Street where it ends at Queen City Park Road, you’ve most likely seen the incongruous graffitied space blocked off by jersey barriers. And maybe, you’ve wondered what it was, or why it was there.

In the 1960s, American cities were jumping on the massive urban renewal bandwagon, which was aimed at revitalizing communities long forgotten by neglect, and the de rigueur of American suburbia. Being Vermont’s largest city, Burlington was having an identity crisis, and figured that Vermont’s largest city should be something more than an unflattering image of blighted industrial waterfront and vacant downtown. So, The Queen City jumped on the urban renewal bandwagon. Their grand vision was a multifarious one which envisioned many future facing wonders; a shiny new downtown area connected to it’s environs by an efficient circumferential highway. They achieved this dream by using the power of eminent domain, and discombobulated an entire neighborhood of primarily Italian immigrants, to build canyons of featureless brick, glass and concrete, with loads of parking real-estate, which reflected the precipitously rising car culture obsession.

Stage two of the plan was to build a highway that would move traffic in and out of the city efficiently. Because Burlington was built on an awkward grid system from the 1800s, the city layout was never met to accommodate an unprecedented population rise or a society where everyone drove a car. Traffic was already piling up and into residential neighborhoods, which was frazzling local residents.

Construction broke in 1965, and the “Southern Connector” was started, creating today’s exit 13, aka, the Shelburne Road exit. But, the project quickly ran into problems.

Directly in the path of the proposed highway was a contaminated swath of swampland wedged between Pine Street and the lake.The Pine Street Barge Canal, a former industrial waterway turned Superfund site, was discovered to be highly polluted by the state of Vermont in the late 60s. If construction crews were to build over the canal, all of the trapped ground contaminants such as coal ooze and gasoline from irresponsible industrial disposal decades ago would all be released into the lake.

Because of this, construction halted, and a forlorn stretch of pavement was left stretching from Shelburne Road to Home Avenue. The only solution was to just block off the remained of the now unusable highway, and divert the exit to dump out onto Route 7. The project could go no further. Plans to finish the highway were proposed for several years, but it wasn’t until 2010 when plans resurfaced again. This time, it was recreated as “The Champlain Parkway”, and the reinvented idea was to merge the highway onto the south end of Pine Street, then turn the street into a 4 lane boulevard with updated pedestrian crossings and sidewalks, creating a main artery to and from downtown. But that too fell into problems, including concerns from south end residents who weren’t thrilled with the idea. Eventually, a compromise was made between city hall and opposed denizens, that include selective signage that only mark the anticipated parkway from certain directions, in an attempt to reduce traffic flow. But in the GPS era, I doubt that omitting signage in certain areas of the city will truly be a solution.

Today, the so called road to nowhere still goes nowhere, There are remnants of many homeless camps behind crumbling jersey barriers, and the local teen crew has converted much into a make shift skate park and a canvas for graffiti artists. It’s an interesting place to walk around on a warm spring day.

Places like this are special – an unusual contrast only separated from the dead eyes of the city by a chain link fence and new growth trees. Here it’s a different world, frequented by mysterious people of all types, all leaving their marks and appreciating what was otherwise left to rot.

The Milton Speedway

A few miles to the north of Burlington is the growing town of Milton, which is nostalgically remembered for being the former home of Catamount Stadium, a legendary stock car racing stadium and a now demolished staple of local culture.

In the 1960s and 70s, Milton had a reputation for being the “race town”, with a strong local culture and two lively institutions supporting it.

In the last century, Vermont had over 22 race tracks, with many being hastily created to assist the growing American car culture and it’s ripple effects. In 1960, the iconic Thunder Road would open in Barre, which was noted for it’s fine and thoughtful construction – something that resembled a modern track instead of the many crude and clumsy oval type tracks that were otherwise being built across the state. Thunder Road was such a success that the Vermont racing community began to brain storm. Building a track in a populated area near major transportation arteries would not only expand awareness of local racing culture, but give it’s participants more places to, well, race.

Milton’s proximity to New York, Quebec and Burlington and land which now was found to be conveniently suited for a racing track would be what would inspire Catamount to be financed and built by 1965 on farmland purchased from Kermit Bushey. A racetrack in town drew in lots of Milton locals and got them involved as racers, spectators or mechanics, which would prove to be one the things that would make the 1/3rd of a mile oval track such a success story.

The track was built to NASCAR specifications by excited local contractors and businessmen, and enjoyed considerable notoriety, those who remember it speak fondly of it. It hosted drivers of all skill, from nationally acclaimed to local heros, and would hold races of all varieties from circuit races to it’s grand finale of an enduro race, which many feel was an insulting way to go out. It was the type of place where car lovers and the curious could witness the latest trends in what would be racing on the track, or the more rigged homemade inventions and the characters that drove them. The locals would come with chips and a cooler full of beers, while the more prestigious could pay to sit in private boxes. All were there for a good time. One summer nights, the stadium could most often be found filled to capacity, and created a loyal fan base. The track would play host to adrenaline and voyeurism until 1987 when the Greater Burlington Industrial Cooperation, who curiously came in possession of the land, wouldn’t agree to renew the track’s lease, leaving Catamount with no choice but to shut down.

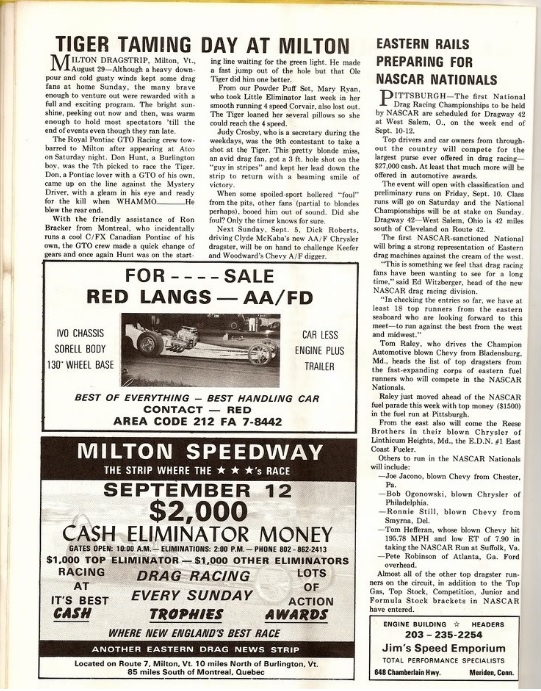

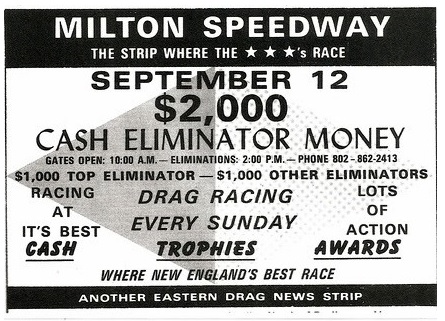

Apart from the stadium, Milton had another monument to man’s love of his car and pushing the limits of societal boundaries; a drag strip. In the 1950s, the young and reckless would find isolated stretches of road to drag race on. In 1963, the illegal sport’s popularity inspired local residents Herbert McCormick and Maurice Bousquet, owners of the former B&M Motors, to finance a drag strip of their own. At a quarter mile long, the track was a spectacle itself, located near the Route 7/West Milton Road interchange.

Billing itself as “The Milton Speedway”, it was apparently quite active in its heyday. Old newspaper clippings show that the speedway was an animated place, and boasted cash prizes and contests. It’s allure drew some notable clientele such as Shirley Muldowney and The Royal Pontiac GTO Racing Crew, who all raced in Milton at one point. But the drag strip’s existence was brief, as the phenomenal costs of resurfacing the road proved to be too much. It was closed by 1971.

In the 1980s, Milton experienced a real estate boom – with the lure of cheap land and close proximity to Burlington – the community soon found itself shedding its old skin as a farming town, and becoming a bedroom community. A few neighbors of mine talked about how they remembered the old stadium when they first built their houses around 1984. Even 4 miles away, they recalled standing on their back decks at night underneath the cool summer skies and hearing the howl of the engines being carried through the dark.

By 1987, partially due to the exorbitant cost of automobile and track maintenance, the stadium closed forever, a sad loss for Milton. The Catamount Stadium was appreciated by the entire region, and its closure was a bitter one. Catamount was very much a community affair. A few Milton residents who I spoke with recalled their fathers, friends and neighbors who used to race there over the years. Today an almost excessive plenitude of automobile related businesses still line Route 7 through town, a fading reminder of a dead era.

The Catamount Stadium grounds were redeveloped to the successful Catamount Industrial Park, which today among other things, houses a helicopter sales business, a warehouse for Burlington based Gardener’s Supply Company and a printing company.

But one relic of Milton’s automobile past does still remain, if you do a little searching. If you head into town on Route 7, towards the grungy stained cinderblock walls of the Milton diner, there is a large vacant and gravely weed chocked field on your right. If you look far back into the field, you notice a perfectly straight segment of roadway that seems to emerge from the otherwise dead ground, and cuts into the woods behind it, going back as far as the eye can see. The pavement is cracked and potholed, weeds are plentiful, and the entrance is blocked by a set of very old Jersey barriers. This is all that remains of Milton’s drag strip.

The drag strip is hard to find now because everything is so grown up around it, so it doesn’t come as a surprise that most people don’t realize this small piece of history still exists. And if they stumble across it, do they know what they are staring at? The overgrown footprint continues for a few miles, until it abruptly ends in crumbling asphalt and birch trees, its ghosts sitting in the branches that tangle over your head.

Today it is a somber place, sitting behind a building supply store and a local diner, pretty much forgotten by the locals. The few that do remember the old strip refer to neighboring Racine Road as “Racin Road”, because the road runs directly parallel to the former strip, and is perfectly straight. Not surprisingly, some like to occasionally race there.

Last I heard, condos are scheduled to be developed on the upper half of the drag strip.

Two stretches of abandoned highways, both with very unique stories to tell.

A great find on Youtube! The Milton Drag Strip, 1963. The identifiable shape of Cobble Hill can be seen in the background.

Links

If you are curious about the Catamount Stadium, or have fond memories of it, there is a great website devoted to it

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my amazing fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations through out the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4