Most people my age aren’t likely to recall Frontier Town, a once-prominent destination turned ghost town in the woods of tiny North Hudson, New York, but there are plenty of people who will tell you that it used to be great, and integral to the once-thriving Adirondack tourism heyday of the mid 20th century.

The Adirondacks are the rugged mountain range that makes up a the eastern half of upstate New York, and most of those mountains are within the 6 million-acre vast and often desolate Adirondack Park, an area about the size of my home state of Vermont and is the largest park within the lower 48.

I’ve mentioned Frontier Town before in an earlier blog entry, but never truly got around to exploring it until recently.

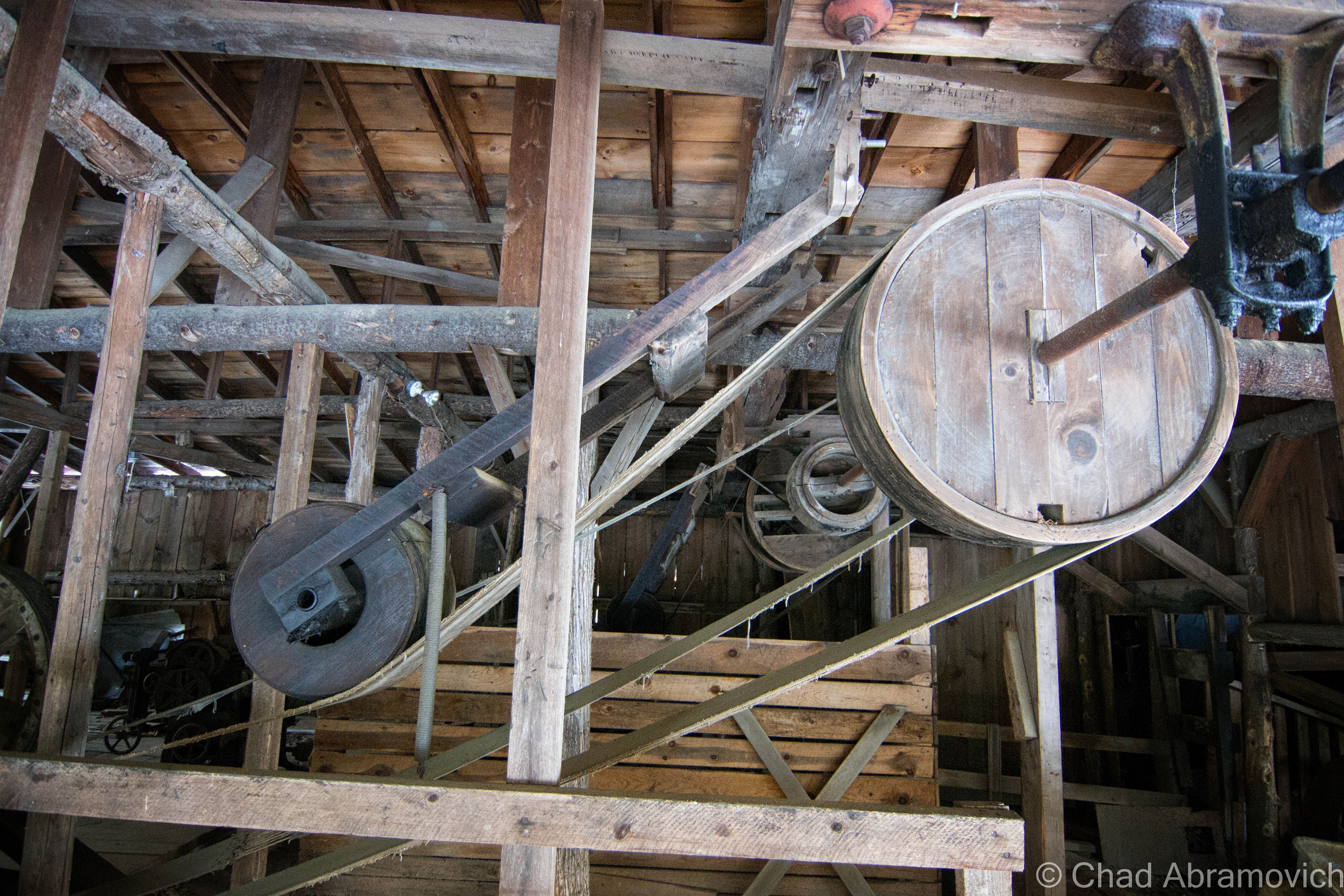

Frontier Town is a massive place, it’s kitschy-cool ruins stretch unassumingly from the roadsides of Routes 9 and 84, and far back out of sight on the sprawling property at the bottom of shady hollows and a myriad of cold swamps that pulse with mosquitoes in the summers. Even in its decay, it still had a wondrous vibe to it that really stuck with me as I wandered around.

Because the property is so large, it’s very difficult to get a good idea of just how much there is to see, until you start exploring for yourself. It’s taken me 3 trips to see a good deal of it, and I still feel like I’ve been unprepared with every visit.

My trips started back in 2012, which were focused on the assortment of abandoned motels and cabins lining Route 9 that once served the motel, and slowly, I would explore my way inwards.

The story of these curious ruins are actually pretty extraordinary. It’s one of those anecdotes that stumbles its way onto the altar of the American Dream and became a venerable benchmark – something that I could file away in the “anything’s possible” camp of things that makes my cynicism do a double-take in a contemporary culture that’s been questioning the truth and the achievability of the American Dream.

In 1951, Arthur Bensen, a Staten Island entrepreneur who installed telephones for a living, was becoming bored with his job, so he started to tour the northeast with $40,000 to find a location suitable for building his dream project; an amusement park.

267 wooded acres in North Hudson would eventually seal the deal, and despite having no construction skills, no idea how to run an amusement park, and no real income after purchasing the property, he went to work!

He was known and admired for his amiable personality, someone who was convincing and charismatic, so much so that he sold North Hudson-ites and locals from neighboring Adirondack towns to help him build the park and eventually be employed there, despite some thinking he was out of his mind.

But impressively, his tenaciousness and optimism paid off, and his fantasy began to take shape. Using his 1951 Chevy, he would drag timber behind his car to build many of the log cabins around the site that still stand today.

Bensen was known for his ingenuity; he was thrifty, a quick thinker and good at improvisation – and it was these skills that ultimately would shape the park so many would come to love. Maybe the greatest example of that previous sentence is how Frontier Town became Frontier Town. His original vision was to build a Pioneer Village, but when opening day was looming, the thematic costumes for his employees/LARPers never arrived.

Bensen made a trip down to New York City to purchase some, but returned with Cowboy and Indian costumes instead, because according to the story, those were the only costumes he could buy in such short notice. But luckily, that just happened to be all the rage in the America of that time.

So, he made some alterations to his blueprints, and Frontier Town was born, officially opening on July 4, 1952 and would continue to expand in the intervening years.

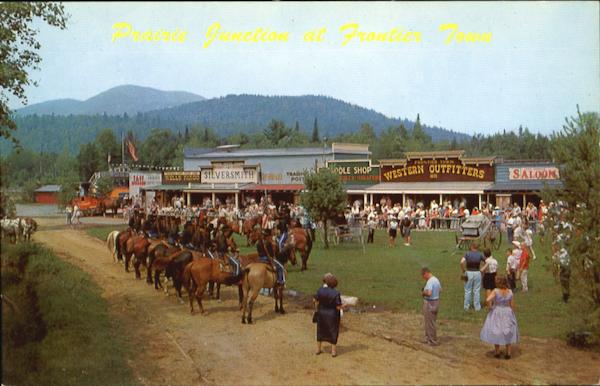

He soon constructed Prairie Junction to keep with his new theme, which was modeled after your trope-y Main Street of a dusty wild west town, and is one of the more interesting areas of the park ruins to photograph today. The low rise wooden buildings were all connected by a broad wooden porch, consisting of a saloon, music hall and a shop selling Western-themed souvenirs and clothing.

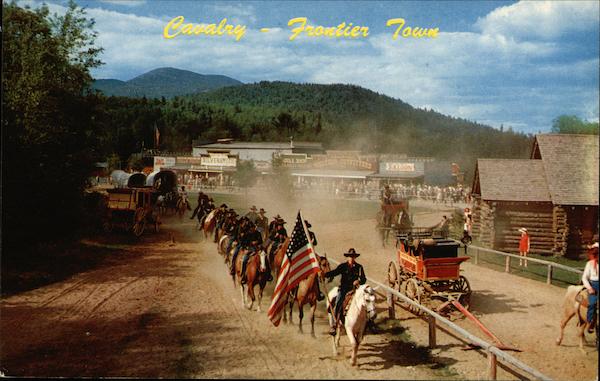

A rodeo area was built nearby, which held two of them a day would and even had shows that allowed children to participate. Stagecoaches, replica era steam trains, and covered wagons would all transport visitors around the park, and outlaws on horseback would “rob” the trains and engage in “shoot-outs”. And it was a huge success.

Frontier Town wasn’t just loved by the tourists and generations of wide-eyed kids who made memories there, it was also loved by the locals.

The park employed many Adirondack area teens, who spent their paychecks on college tuition. Many friendships and romances were also forged here, some which would last lifelong, and would later be recalled wistfully on Frontier Town message boards and fansites that pop up on Google searches about the place.

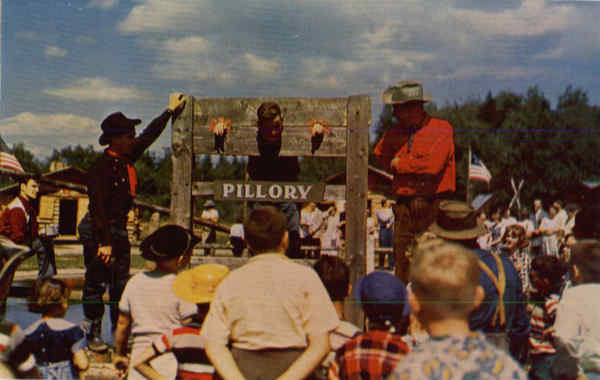

Employees wore period garb and would teach bemused sightseers how to do thematic daily tasks that our frontier predecessors did back in the day to survive. Stuff like churning butter, demonstrating how yarn was spun, or cook pea soup in an iron kettle over a fireplace, which was said to be a favorite of loggers in the Adirondacks.

Unfortunately, like real western frontier towns, New York’s Frontier Town would also go bust after it came to its peak popularity in the 1960s and 70s. The times were changing. The construction of the Adirondack Northway would lure traffic to bypass North Hudson and would make a large reduction in travel time. Now, sojourners no longer needed to depend on Route 9 to get to the Adirondacks from New York City and any point in-between.

Some speculate that the park really declined when a new transgressive era ushered in parents becoming uneasy with their kids playing with guns, which was more acceptable when Westerns were all the craze on TV and the silver screen.

As one Frontier Town enthusiast wrote on a comment thread; “Cowboys and Indians were big time. Every kid had a gun and a cowboy hat”. Others blame broader travel opportunities that came with the construction of interstate highways and air travel, making places like Frontier Town obsolete.

In 1983, a tired Art Benson sold Frontier Town to another development firm, and would pass away 5 years later. The park was closed until 1989, re-opening with additions, such as a miniature golf course. But it was a short rejuvenation, and in 1998, Frontier Town closed for good due to failing finances and weak attendance.

The property was seized in August 2004 by the county for past-due property taxes. The stagecoaches, trains, buggies and the tracks were all scrapped and sold, as well as other paraphernalia. Collectors can still find mementos at Gokey’s Trading Post just down the road, which is where a lot of Frontier Town relics ended up during the massive auction after the park’s closing and appears to be one of the few remaining businesses in town.

Today, awkward and fantastical ruins falling apart in silence underneath the Pines are all that remains of Frontier Town. A walk around the property reveals the tragic process of disintegration and entropy which is both sad and breathtaking to behold and makes me reflect on society’s impermanence.

I visited during the dark wintery cold of January, and returned during a far more pleasant 50 degree April Sunday, so my photos are a mixture of winter and early spring shots.

When I took my research to the internet, I found a cool Facebook page, Frontier Town Abandoned Theme Park Now And Then, with tons of great old photos to gaze at. It’s incredible what the transformative power of nature can do to a place in a short time.

I was really charmed by this place and its story. Researching it had a certain inspiring magic. I love how one guy who was a layman just decided to go for it, and managed to create something that’s had a humongous impact and subsequent ripple effects on the Adirondacks, and a generation of people who were coaxed by its remarkably creative atmosphere. It’s a genuine example of the American dream. Who knows, maybe Arthur’s story can help inspire future dreamers (or amusement park builders).

Since I’ve posted this – the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and the Adirondack Park Preserve have rehabbed Frontier Town into a really cool looking campground and equestrian center – and named it in the park’s honor. I’m a bit sad to see it go but was excited to hear that the property is now fun and beneficial to town of North Hudson.

Frontier Town in its Postcard Prime

Frontier Town, 2015

Joining me for my adventure was my friend Bill Alexander, creator of Vermonter.com, who filmed our walk around the grounds. Check out his write up and video below!

Return, Summer 2015

As much as I openly complain about Facebook, and how I find social media more unnourishing and exhausting for me, I have to admit that it’s also been a huge boon in terms of networking and keeping this blog’s momentum in a direction that’s not backwards. Making friends when your an adult is a hard gig. Thankfully, I was able to network with and befriend other explorers over Facebook who dwell all over the east coast. Eventually, we started to organize meet ups with willing participants. In June, 2015, I would meet two cars worth of previously virtual photographer and explorer friends, and Frontier Town was one of our stops on a full day excursion. But, a day of exploring before we arrived in North Hudson had drained my camera batteries, so I only was able to get a few pictures under the coolness of a soft summer evening.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my amazing fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations through out the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4

Side Note: There is a ghost town in the mountains behind Frontier Town. If you’re curious, click on

Side Note: There is a ghost town in the mountains behind Frontier Town. If you’re curious, click on