“Wow, how does a place like this even exist?” mulled my friend aloud, lost in her own luminous reverie. I had seen photos of this beautiful dereliction online, but I was just as awed, as the stagnant cold inside stung my hands.

The early morning wintry cold was still hanging over the misty hills of Bolton flats in a hundred shades of blue as we departed for southern New England. While we drove we sat in silence, with heated seats, coffee and the wonderful sounds of Caspian coming through my iPod. After a few hours, Vermont’s brown frozen hills gave way to eight lanes of interstate traffic and lots of Dunkin Donuts signs.

Thirty-two years of fluctuating New England weather and zero upkeep had rotted out the drafty interior. The metal stairwells became stretches of rusty spiderwebs, some were completely untrustworthy. The snow that fell through between broken roof was so loud that you would have thought it was thundering outside. The thick brick walls oozing with slime and glazed by ice blocked cell phone reception pretty well. I received a few texts sent by my friend asking me where I was, hours after she had sent them and on the road back to Vermont, which I guess meant that contact in case of emergencies would have been pretty unaccommodating.

The complex appeared to be a utilitarian and symmetrical layout of two large spaces adjoined by a central row of offices, bathrooms, and mechanical areas. But upon closer and intimate inspection, I was actually more and more surprised at just how many rooms and levels there were, packed in by a labyrinth of confusing staircases and elevated runways. Some spaces were more or less original to their inaugural construction at the turn of the last century, and in the throes of the shifty ways of time, more were accommodated. There were quite a few dank 1970s office spaces put up hastily in areas that contained the infamous giveaway vinyl wall paneling and drop down ceilings, all which were accordion-ing now thanks to precipitous moisture. Some spaces were utterly unidentifiable under the entropy, with collapsing floors and sketchy staircases that lead into ambiguous soggy blackness above. But it was the two main rectangular chambers and their brawniness of broken glass and steel that I was interested in. These cavernous spaces had quite the compendium of artifacts left behind; from magnificent and remarkably intact machinery, actual steel rails still embedded in the floors, to just about anything you can fathom that had somehow found it’s way inside and subsequently left there to waste away. There’s a lot for a person to think about as they walk along the crumbling floors inside this illusion of another world. Just watch out for nails. There are plenty to step on.

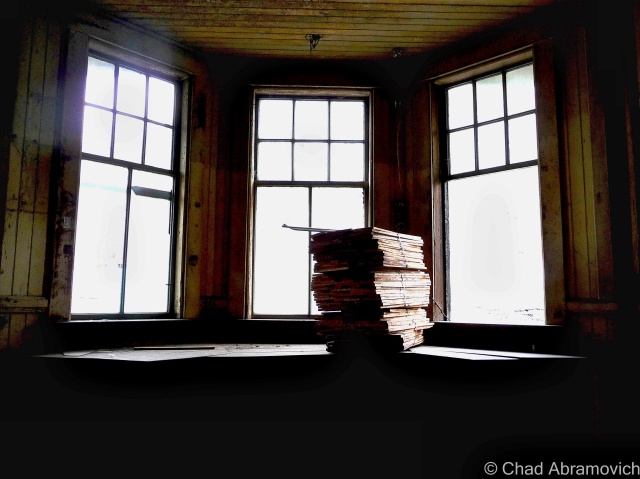

The most interesting of things left to rediscover was the extraordinary amounts of sordid books, paperwork and filing cabinet miscellany (and their accompanying filing cabinets) that had been left behind. I’m talking entire floors filled with wall to collapsing wall of old records mummified in decay. Most of the paperwork was illegible, but the oldest date I was able to find was 1931. Another friend and explorer had joked that a photo of mine was the literal embodiment of “squishy”, but as of now, no destination has been able to surpass The Pines Hotel as my “squishy-est” explore, though this place is definitely a contender.

Though we live in a world that has largely been explored, mapped and reclaimed, these human-made spaces become utterly fascinating after their functionality ceases to exist. The mystery continuum of their inner spaces become sort of last frontiers, as nature begins to reclaim everything that has been forsaken by us, transforming these spaces into something incredible. It’s on these explores that I like to attempt a little amateur forensic archaeology, and try to pick at the bones.

The suburban New England town I traveled too became the chosen plot of land for the formerly prestigious Boston & Maine Railroad to build their rail yards and repair/manufacture shops in 1913. What is considered to be one of American’s oldest suburbs was built up in the adjacent area to accommodate the growing need for laborers, many of the garden enhanced neighborhoods eventually were built up over old track beds that were once spur lines leading back towards the roundhouse, depot and loading docks. The continuously shape-shifting property grew to massive scales as the railroad industry became a future facing wonder, as growing mill towns and their populations created a ravenous market. That is, until the automobile became de rigueur.

The popularization of the automobile and the trucking industry seems to be the harbinger of death for a good amount of the ruins I visit, and this seemed to follow the same storyline, as both the automobile and leveling of the same manufacturing that created the demands for the railroad, murdered it. The railroad had grown so much during its boom years, that it went into unpayable debt for the miles of tracks they laid and smaller companies they acquired in the throes of good-natured greedy competition. Towards the latter half of the 20th century, the railroad industry indignantly stepped back into a darker corner of civic and popular culture, and the massive campus was now useless.

The B&M went bankrupt in 1970 and despite efforts to reorganize and restrategize, became a ghost by 1983, when it was bought by another regional rail company. By 1984, the complex was abandoned altogether because all that space simply wasn’t needed by the diminishing industry. But, not before they left a naively irresponsible legacy of destruction and negligence behind them, as the massive yards were also used for toxic waste dumps and a place to haul train wreck shrapnel over the years, which earned the place an official designation on the Superfund site list, a bone of contention that isn’t even expected to be taken seriously until 2031-ish because like everything else, the EPA doesn’t have the money. To the locals understandable displeasure, there was quite a bit of opacity about their houses abutting a literal toxic waste dump – information which wasn’t even made widely public until some neighbors did a little digging in the late 80s when a pervasive chemically smell began to waft through side streets near the industrial park, and became an uncelebrated normal.

I was able to find a few articles on the local public radio website that explained that the entire 553 acres are so swamped with pollution – ranging from asbestos, arsenic, cadmium, lead, selenium, petrochemicals and wastewater lagoons that it not only earned a spot on the national Superfund database list, but it’s one of the worst in America. “You couldn’t leave your house to go out and even have a nice barbecue because the odor was so bad”, said an interviewed resident recalling how bad it was a few decades ago. To makes things more apprehensive, The EPA says human exposure risk is still “not under control”, though it seems far more controlled today than when the report was written. I guess I can cross off walking around a toxic waste site off my bucket list, regardless of the fact it wasn’t on my list.

Today, most of the former property has been reincarnated as a shabby looking industrial park. The largest railway in New England has it’s main headquarters here still, that sits directly in the decrepit shadow of the abandoned shop buildings I was walking around, among a few other places with no-frills signage and creepy vacant looking front entrances. That being said, this is still an active industrial park, with employees, cops, and on my visit, guys who operate plows, that are present on a daily basis. Unlike me, who technically has no reason to be here other than curiosity. The rail lines that hem in the property are also still in use, and some of the industrial businesses in the park receive rail traffic.

There is always a certain reward to risk ratio that I use as the dichotomy or gauge of how I treat my explores. On this trip, my friend and I and my friend decided to simply walk towards the buildings with our cameras, as there was no way we could get inside without someone seeing us, and I didn’t drive through three states just to turn around. The man in the plow noticed us as he was relocating a snow drift. We all mutually nodded our heads in affirmation and confidentially walked inside. We were exploring for four hours or so, and the cops never came, which was great, because this fascinating locale has easily turned into one of my fondest explores. This is one of those places I could return to multiple times and have a different experience at.

But I wouldn’t take that one fortunate opportunity for granted. I know a few people who have been dragged out by the powers that be before, which is why brushing up on trespassing laws in other states isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Until some serious clean up and the accompanying scrutiny happens, these hulking and fetid ruins and all their soggy decay are more or less, in limbo.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my amazing fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations through out the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible. Seriously, even the small cost equivalent to a gas station cup of coffee would help greatly!

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4