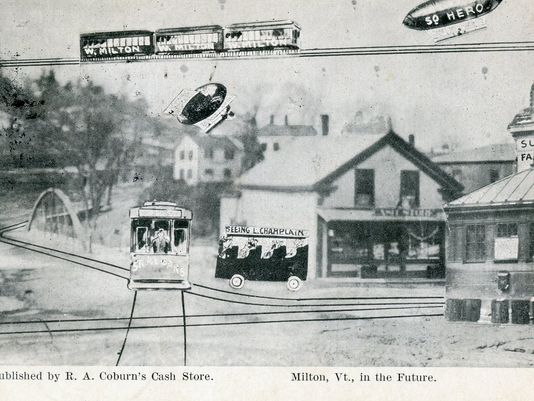

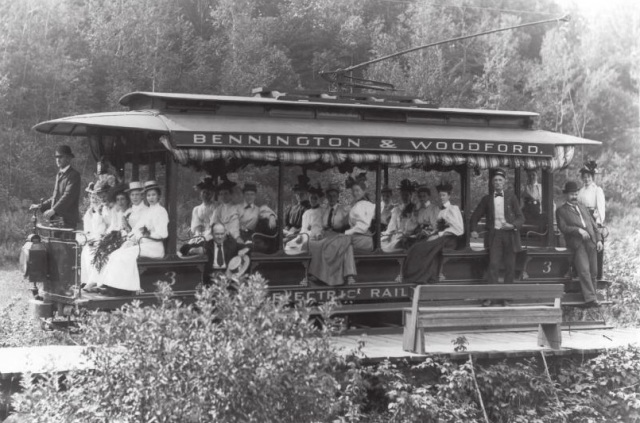

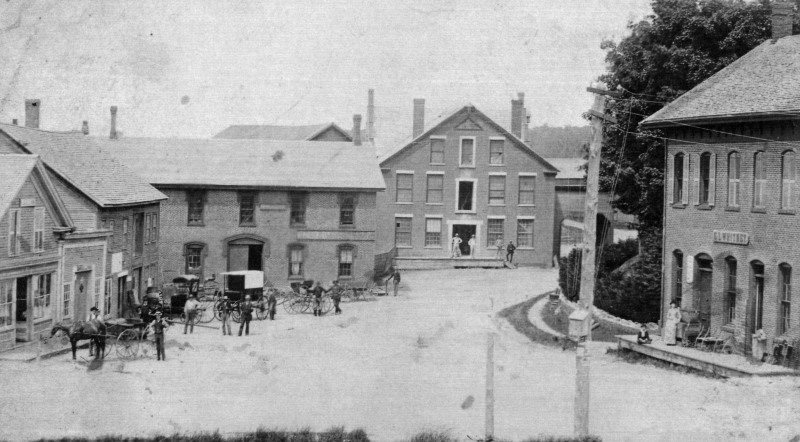

This old postcard may be one of my favorite finds from the Milton archives. Published by Raymond A. Coburn, who owned the pictured general store in Milton from 1908 until the flood of 1927. This image of “downtown Milton” depicted a cartoonish almost satirical image of what town had the possibility to be like in the future. That vision included blimp taxi service to South Hero, which I still think would be sort of cool. Today’s Milton of the future has a CCTA bus line. | photo: Milton Historical Society.

My thoughts on Vermont weirdness often drift back to Milton, my former hometown. I suppose this is where I would further enhance that sentence with an explanation, but to be honest, I’m having trouble coming up with an angle on this. It’s where I grew up, and something about spending a third of my life there has just tattooed it into my framework. It’s where my love of the weird and the offbeat began from inside a quiet suburban bedroom, and began to proliferate outwards – which would become one of my most distinguished aspects of my personality, and why this blog now exists.

As I grew older, I let my burning curiosity get the best of me, and began writing down all the urban legends and stories from my childhood, and all the accounts told to me over the years. This was a ritual I began to love, because I was quickly finding out that Milton was a fascinatingly storied town!

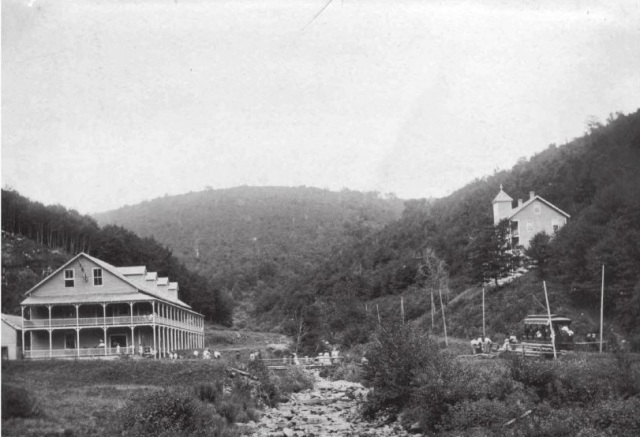

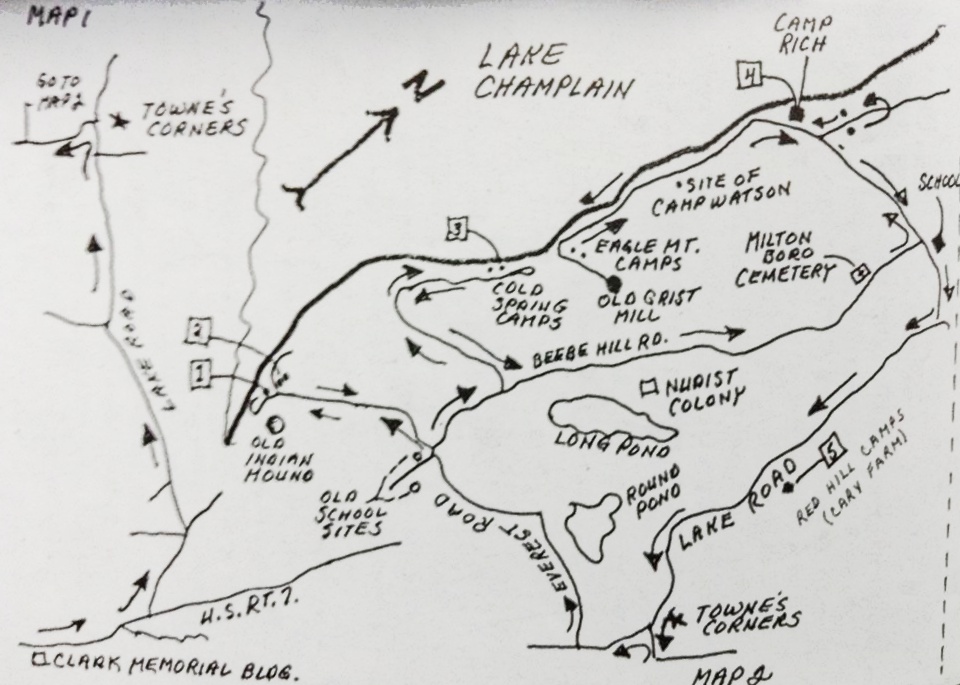

Its geographical area is unassumingly large, ranking 10th largest in land area and 8th in population (10,352 bodies at the 2010 census). All of that space is a perfect for hemming in obscure things and historical oddities. In the 1920s, aviation enthusiast and innovative inventor Paul Schill built an airport in town, where Sears and Ace Hardware are today (which accounts for the pancake flat plot of land along Route 7). But his goal of putting Milton on the map as an aviation manufacturer hot spot died in the beginnings of the great depression after he declared bankruptcy. In the later half of the 20th century, we were one of the premier racing towns in the northeast, with the Catamount Stadium (something I’d love to write about in great detail) and a drag strip drawing enthusiasts from around the region. These things have also became faded ghosts with the changing of the times.

Over the years, Milton would be a place where I would begin to shake hands with a lot of ghosts. Some were metaphorical; conjured from inflicting wounds laid upon to me. I began learning a lot about my Aspergers diagnosis in this town and still remember my lonesome youth rolling and stumbling, figuring out how I processed information in different ways from the rest, and how I often felt powerless because I didn’t feel like I understood the world around me, learning the rules out with the wolves.

But some of these ghosts were real. A former friend once told me about how their Bert’s Mobile Home trailer was haunted by the ghost of a little girl, who particularly liked a long narrow hallway connecting the bedrooms behind the living room. Though I’ve spent quite a bit of time there in my past life, I never had a run in with her. But I do recall the hallway always being dark and creepy, even during the day, which is a good breading ground for spook stories. When I asked the family about the girl, it became more complex and amorphous like these stories always tend to do; there were no records of any young girls growing up or dying there, making this story a weird mystery. But, they somehow knew she was there.

There is said to be a house on Main Street where things literally go bump in the night, perhaps because it used to be a funeral parlor in the last century. Weird lights and objects in the sky have been reported around 900 foot Cobble Hill for a few decades, and local lore tells of a haunted island in man-made Lake Arrowhead where a young woman was murdered by her jealous stricken husband in the late 30s, when he became enraged after the men of town kept admiring her. And, I’ll always remember this arbitrary point of non-trivia about Hobbs Road. Though the paved thoroughfare was named after a farming family, my friend once joked to me as he was reading the directions I wrote down so he could find my house; “I noticed that your neighborhood was off Hobbs Road…did you know that Hobbs is an old name for the devil?”

The more curious I became, the more I began to take comfort in the quiet company of weirdness and lore. Some mysteries I would have the pleasure of investigating, others still remain lost somewhere in the haze. Either way, both sets of ghosts would successfully haunt me for years to come.

Underneath The Ground

One of the most impressionable stories from my childhood told of a clandestine tunnel that started in the basement of the Joseph Clark mansion and ran underneath several old homes on Milton’s Main Street.

The stately Joseph Clark mansion, perched on a slight rise above Route 7, used to be the town offices and library back in the 1990s, which was the time when I picked up on the story. According to some, one of the house’s long dead builders is still there, and may be responsible for the next part of the story.

Kids in the library used to do what kids do best, and venture into places they weren’t supposed to. One of those places was the tunnel. But some would come running back up the stairs, visibly shaken, and tell the librarian that they were chased away by a man in the tunnel they thought was a security guard, whose presence was announced by the sound of heavy footsteps approaching them and then a glimpse of his tall dark form. But, the librarians would be confused and explain that the library had no security guard.

Unfortunately, that was where the story went cold. Was there really a tunnel underneath Main Street, connecting many of the town’s oldest homes together? If so, what was it used for? Popular theories guesstimate that it was constructed for use in the underground railroad.

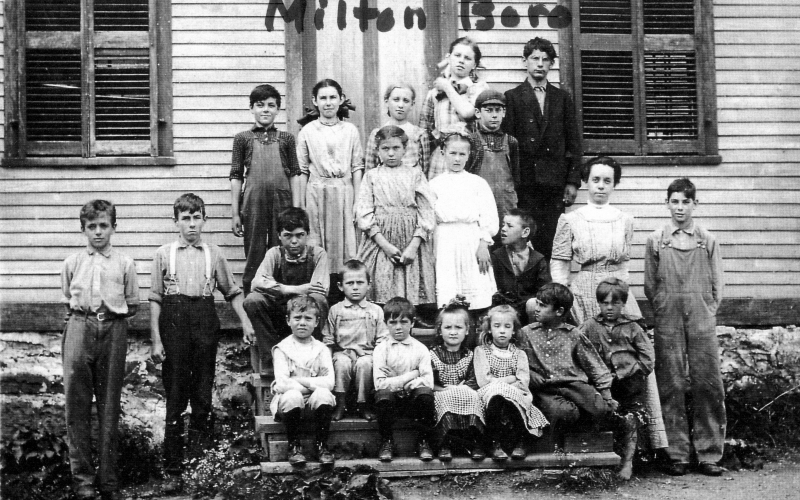

Lorinda Henry of the Milton Historical Society was kind enough to sit down with me and help me in my search for answers. Meeting in the Milton Museum, which is pretty much the town attic that sits in an old church, we dug through countless unlabeled binders and boxes, but sadly, any information containing the tunnel wasn’t in their archives, or had long been lost. But the builder of the Clark mansion, however, was well documented.

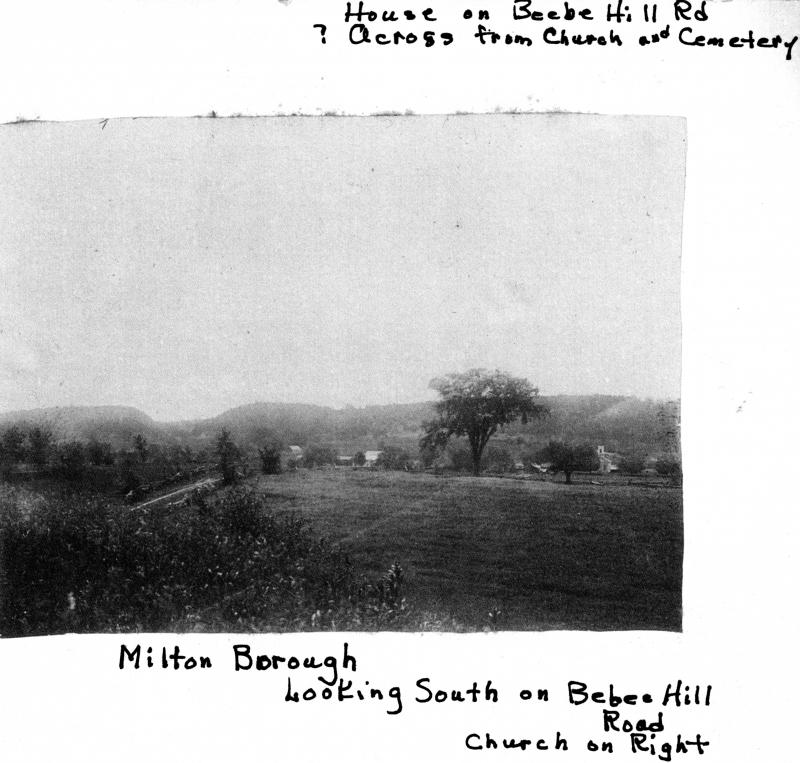

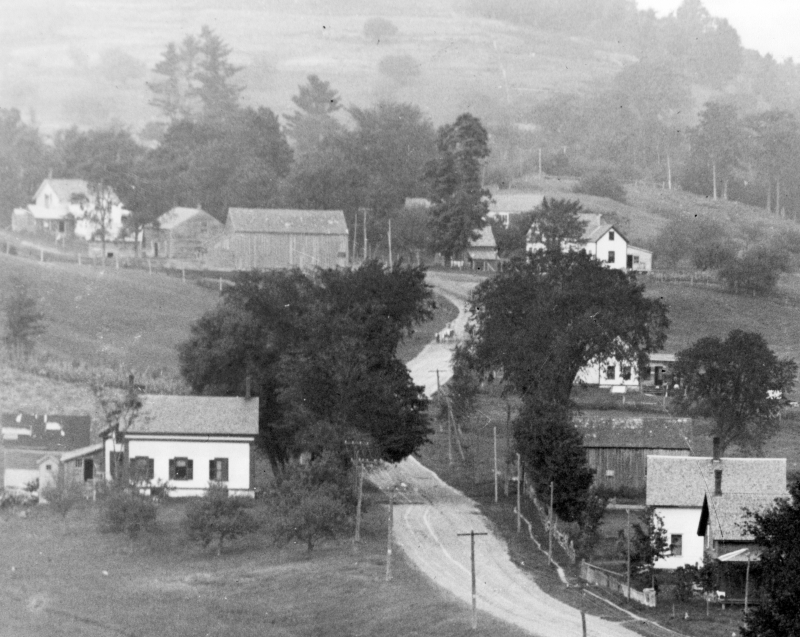

After Milton’s official chartering in 1763, settlement was lackluster for the next 30 years. West Milton on the lower Lamoille banks, became the first part of town to be developed. A few miles up the river was a part of town that was known as Milton Falls, which would be the area around present day Main Street. In 1789, Elisha Ashley would survey the first east-west road in the Milton Falls section of town, by running a straight line from the Westford/East Road intersection, to a stump on the Lamoille River. Noah Smith, one of Vermont’s first lawyers, owned most of the land around what would become Main Street and Milton Village.

Joseph Clark was one of the earliest settlers in town, and his business endeavors made him both one of the wealthiest and most influential residents in Milton. He came to Milton in 1816, a year known by Vermonters as eighteen hundred and froze to death, because of the unseasonably frequent snow and frosts that caused widespread crop failure across the northeast. It’s no surprise that some superstitious Vermonters saw this as the coming of the end of the world.

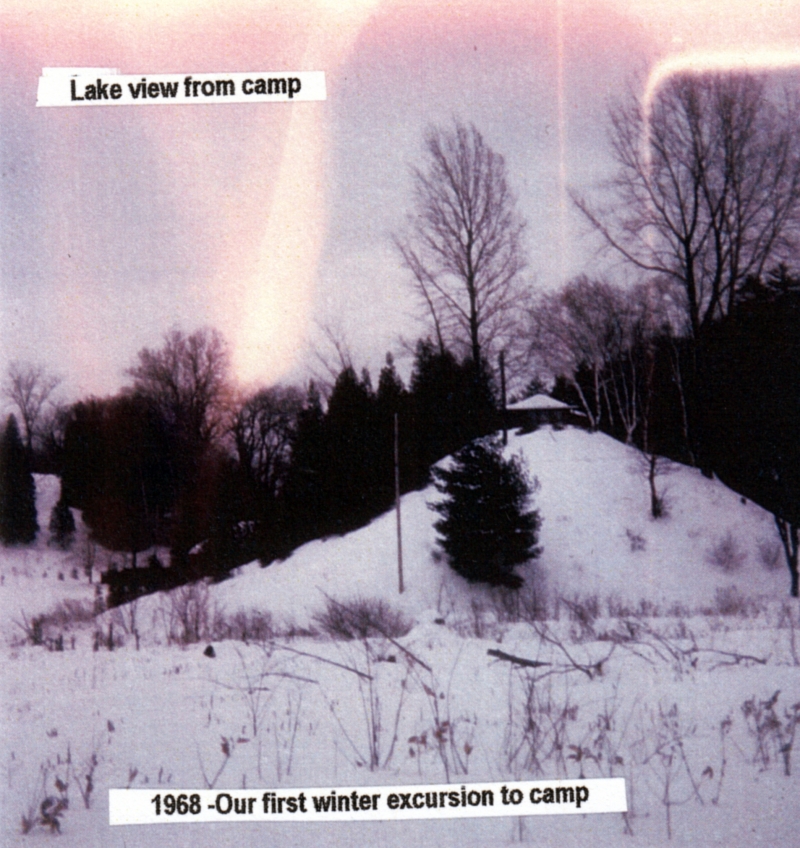

But while the crops were failing, Clark and his partner Joseph Boardman saw opportunity in the rich pine forests that covered most of Milton, and hired crews to harvest the fine timber. The logs were floated up Lake Champlain to Montreal, before they were shipped to England, many to become used by the Royal navy. By 1823, he would purchase a sawmill in West Milton to process the raw timber. But by 1830, woodlands were replaced by agricultural land, and Clark decided to invest in other opportunities. He would build a gristmill in Milton Falls, then move into the brick mansion on Main Street that now bears his name. Later, he would build himself a two story brick office building where Main Street meets River Street, today’s Route 7. Clark’s move and investment in Milton Falls would lure more people and business endeavors there, and make that the new hub of town.

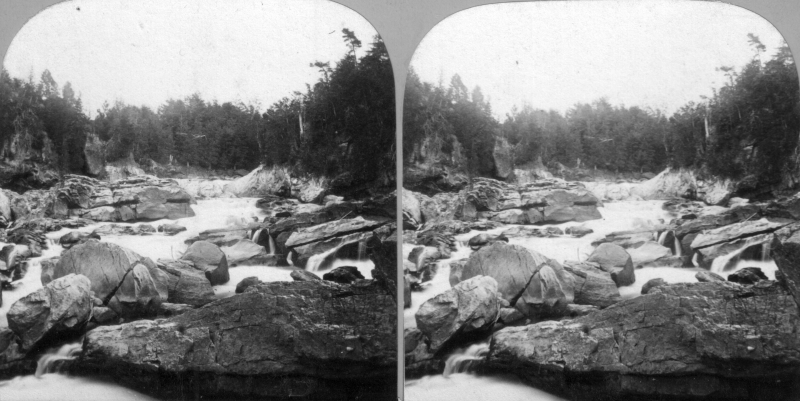

Here, the Lamoille River and gravity worked together to form about 5 waterfalls in a few miles of one another constricted in a rocky gorge, before relaxing at West Milton. These falls were ogled and soon sought after for industry. Some however also envisioned bravado and a way to kill boredom. In the 1800s, a growing number of young people in the northeast were jumping in barrels and going over any waterfalls they could find, which would achieve both getting mentioned in the newspaper and sometimes death. I once heard many years ago that around that time, a local boy and self-described dare-devil went over Clark’s Falls in a barrel. But to my huge disappointment, I couldn’t find any verification or information on this man or his leap over the falls. I liked that anecdote enough to include it in this entry though.

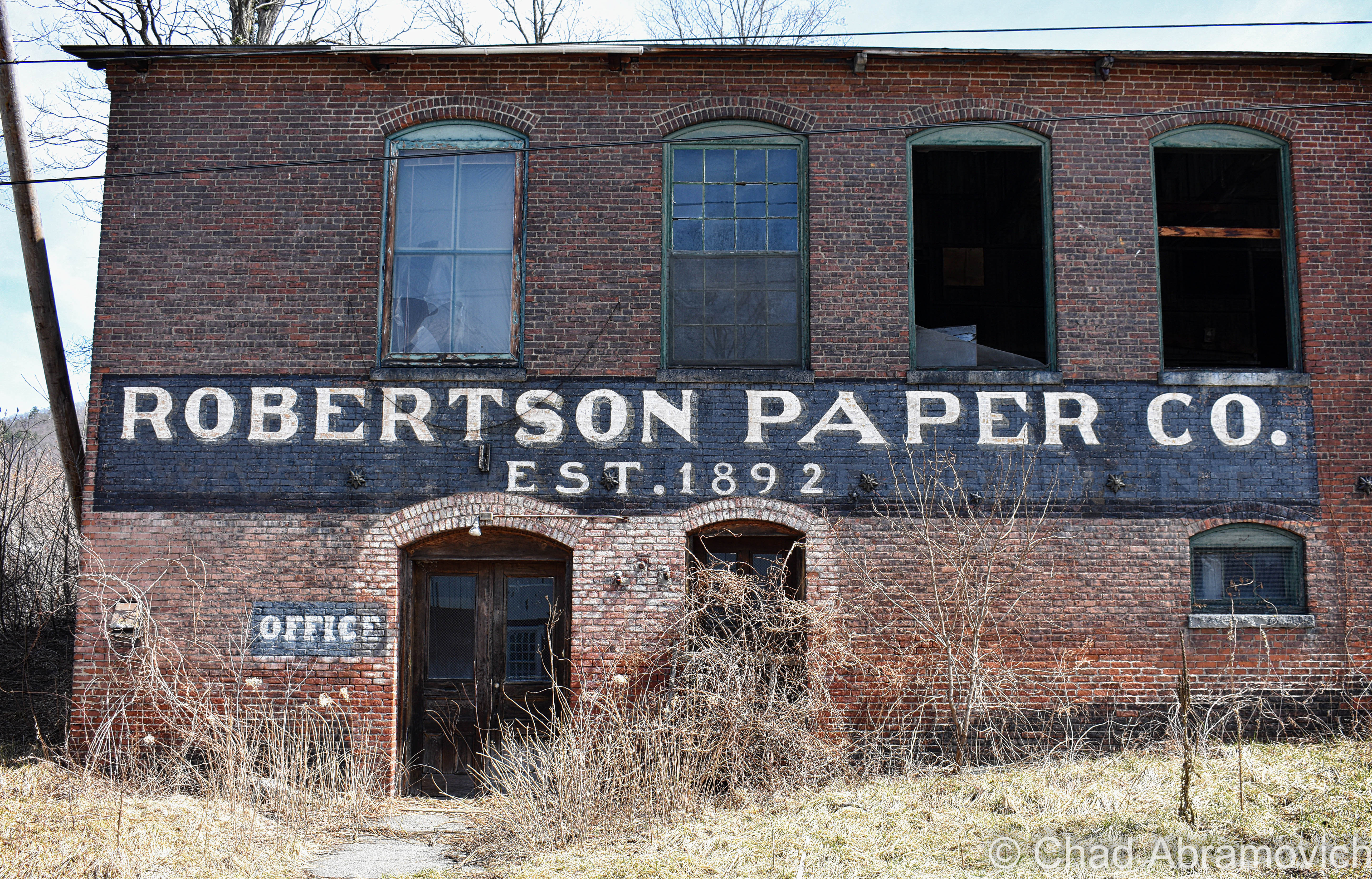

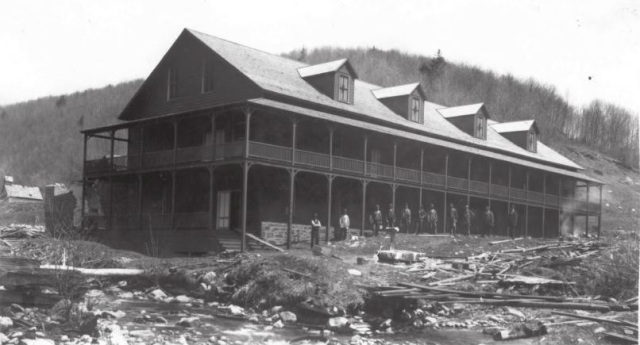

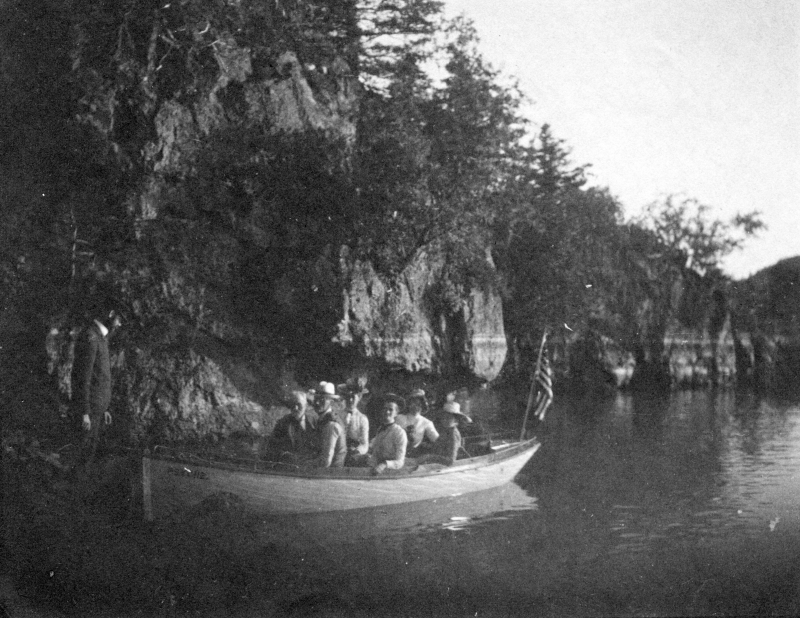

Railroads were rapidly spreading their steel arteries across the United States, bringing people, opportunity and growth with them, and because these things were vital for business exploits, this caught Clark’s attention. Partnering with John Smith of the Central Vermont Railroad, they worked to get some tracks built through Milton. In 1845, Milton had a rail line and accompanying train station, and that benefited the town greatly. After the civil war, the railroad brought vitality to the town’s burgeoning summer tourism industry and industrial mainstays like the former Creamery, a building which has shaped my love of exploring and photography.

Clark would continue to remain active in town affairs until his death in 1879. The house was passed down to family members until 1916, when Joseph’s granddaughter, Kate, deeded the house to the town of Milton to use as the town offices, and remained so until 1994 when it was reverted back to a private residence.

Lorinda speculated that the former gristmill behind his mansion could have warranted the construction of a tunnel, which would have sat where present day Ice House Road is. The house was built on a slight ledge, which would have made the tunnel a more convenient way to travel from one place to another, especially in the grueling Vermont winters. But there was no way to know for sure.

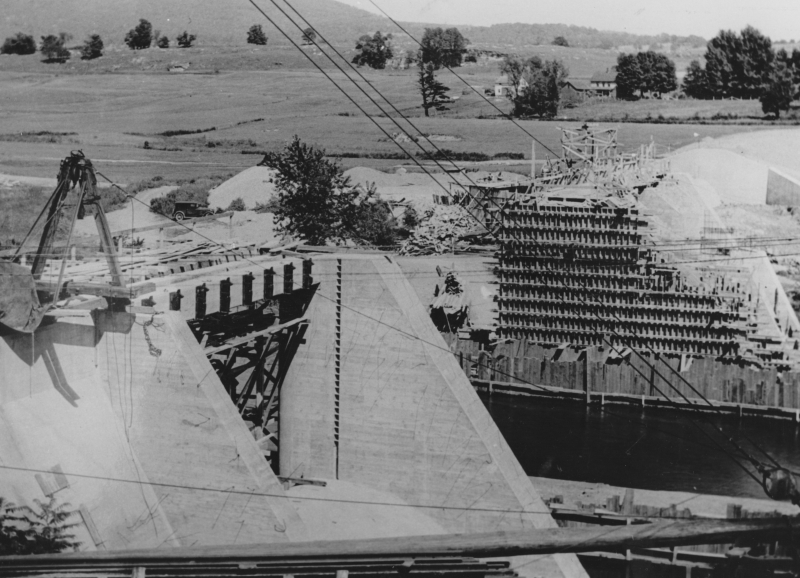

The mill and most of the development near the river were washed away during the flood of 1927, making investigations almost impossible.

It was later told to me that someone knew of a “thick iron door” found in the basement of Joseph Clark’s former office building on the corner of Route 7 and Main. This was one of the few buildings on River Street to survive the flood of 1927, so that claim seemed pretty credible to me. (But if it were built at a later date, I would be really curious about that mystery as well)

Geography would aid me here. The building was built into a ledge that forms the beginning of Main Street hill. Right above sits the Clark mansion. This means that a door in the basement wall would have lead to some sort of subterranean chamber, which may have been a tunnel.

The historical society told me of a former resident and her mother who once lived there, and claimed to have seen the iron door themselves. The facts seemed to be finally adding up here, but it seems my request for information was a few years too late. The building has since been sold, and it’s current owner denies the existence of a door firmly and doesn’t want to talk about such things. I attempted to reach out to the previous owners who brought forth the iron door sighting, but they had told the historical society so long ago, that their contact information had since vanished.

Another suggestion illustrated that the tunnel once ran all the way up the hill to the abandoned creamery on Railroad Street. And sure enough, there is a walled up door in the basement that once did lead to a tunnel. Could this be the proof I was looking for? I did a little digging around (literally), and talked to a former employee. As it turns out, the door did lead to a tunnel, but it wasn’t the tunnel. It ran significantly shorter, just over to the brick building next door which was also owned by the creamery at the time (now converted to a private residence). But that tunnel also had its notoriety. Former creamery employees and older Miltonians wistfully admitted that they used to sneak down and party in that tunnel, those shindigs usually included spirits and cigarettes, while the creamery was in operation and even in the years after it’s closing.

The tunnel story seemed to be disappointingly falling apart. Though it was cool to think about – practically, it didn’t make sense. If we stick to the theory of a tunnel running all the way underneath Main Street, why would such a long tunnel need to be constructed? What was it’s purpose? To further deteriorate the story, the stately homes on Main Street were all built around different times, meaning their construction most likely didn’t accommodate the existence of a tunnel. And to prove this, I had spoken with a few Main Street residents who had never even heard the story of the tunnel, but all assured me the only way into their homes were through the front or back doors.

Vicious Waters and Dislocation

It wasn’t until some time later, after this project had been pushed to the back of my to-do list that something came up which immediately pulled it from memory. A Facebook commenter who knew that I was attempting to get to the bottom of this sent me a message and shared a personal account with me. As a kid in 1960s Milton, he used to play with his buddies down near the river, and he recalled seeing a cave like opening set back in the cliffs near the dam. Popular labeling at the time dubbed it as a tunnel. He even remembers his parents admonishing him and telling him not to go near it because it was likely to be dangerous. He never did, but speculated that it may be what I’m looking for. He also said that some of his friends claimed to get inside, but couldn’t recall any more than that. For all we knew, they may have been embellishing the truth.

One gloomy summer afternoon in August, I set out with a few friends to dig around the Lamoille banks, trying to find the telltale opening. That part of town has long been awarded an odd moniker by local youth who call it The Vector, which is a robust sounding name, but I can’t seem to relate it’s actual definition to the rocky gorge spanning from the Route 7 bridge to the bottom of twisting Ritchie Avenue. But the name has proven very successful at sticking into the flypaper of local culture. I grew up knowing that area as The Vector, and still do.

While doing our amateur urban archaeology, we found a surprising amount of items along the river banks, in the waters and even stashed in crevices that ran like veins through the crumbling rock ledges. Broken pieces of China plates, old glass bottles, rusted tools and even the remnants of an old truck lay trashed down in the rocky gorge, things that blurred the lines of being considered an artifact or garbage.

I knew this area was hit hard during the flood of 1927 and artifacts, cars and even entire homes were swept up in swollen brown tides down this part of the river, depositing much that still rests below wet rocks and Hemlock trees today. I even was able to dig up old newspaper accounts that were printed when the disaster was happening. One vivid memory was reported by a woman, who watched an entire house be swept down the river, almost entirely intact. She said she was able to look inside a broken window and see someone’s bed that had been turned down, as if the person was just about to turn in for the night.

A better understanding of the flood also gave me a better understanding of the area I was going to explore. Not surprisingly, its popular with people who like to metal detect who are still finding things transplanted from the flood and years onwards, so seeing all of this rubbish down there wasn’t a shocker. But something didn’t quite fit. One odd find was that a certain crevice seemed to be filled with trash – but it was put there by someone. This wasn’t naturally occurring. Someone had been down there at one point, trying to fill it up…

After a while of picking at the pieces and dislocating rocks, we were able to catch a peek deeper into the crevice, which expanded far back into a dark rocky chasm. It was evident that there was, in fact, more to see, and it did extend backwards, but I knew it wasn’t what I was looking for. Granted, the space had long been filled in by dead leaves and garbage, but it seems too narrow for what could be considered a tunnel. No man could seemingly fit back there, without the aid of tools and a great deal of ensuing noise. Either way, I stopped my efforts.

I came up empty on August’s exploration, but in October, another lead would unexpectedly manifest itself, and it was promising. Meeting up with childhood friend Zach, I found myself in a location I normally avoid, a hole in the wall bar and pool joint in Essex Junction.

I came up empty on August’s exploration, but in October, another lead would unexpectedly manifest itself, and it was promising. Meeting up with childhood friend Zach, I found myself in a location I normally avoid, a hole in the wall bar and pool joint in Essex Junction.

I was there to speak with a friend of Zach’s, someone who grew up in the Clark mansion and knew the building well. The house still belongs to her family today. When Zach had mentioned I was interested in the Clark tunnel, she said she needed to meet me in person.

And, she happened to be the bar tender who served us our drinks. Those who know me well are aware of the great cosmic relief that I often feel far more in my element in a location that is “off limits” to society, as opposed to legally being inside a dimly lit bar underneath a perfume of cigarettes and sweat. But she was all smiles, and her enthusiasm put me in a good mood. “Oh man, that house is definitely haunted!” she exclaimed. Though that wasn’t exactly my crux, I had to chuckle. “As the story goes, the house might be haunted by Joseph Clark?” I questioned, now amused.

“Nope” she replied. “We actually think it’s a woman”. Old records state that Clark was once married to a Colchester woman; Lois Lyon, which possibly could explain this. Over the years, she and her family have heard the sounds of high heals clacking on hardwood floorboards upstairs, and of course, whenever one would go and investigate, the second floor would be empty. She also recalled the upstairs being creepy as a kid, a place she wasn’t all that fond of hanging around in. Other accounts like phantom cold chills and the unmistakable feeling of being watched upstairs she also said were pretty common. But damn it, was there a tunnel?

Much to my pleasure, the mystery was finally confirmed. There was a tunnel, and she has seen it! Now to get to the bottom of things.

Opacity

In the cellar walls of the Clark mansion is the clear outline of a door that sits well below the grassy lawn, now sealed up. But the distinctive outline of a door cleared up all skepticism. Also in the basement was another relic I found to be very cool – a massive cast iron safe that once belonged to Joseph Clark still sat in the wall. Though much of the mansion had been renovated over the centuries due to its many reincarnations, a few authentic pieces of the place still remained. She explained to me that the tunnel had to be sealed up, because local kids kept getting into the tunnel and using that as passage inside the building, where they would steal and break things. This happened even after the building reverted back to a private residence in 1994, so actions finally had to be taken. What a shame. By now, the tunnel is more or less unsafe to enter as well, due to neglect over the years.

However, I don’t want to deceive you folks. This information was directly given to me from the niece of the current building owner, that owner also declined my phone calls to seek a tour of the place, which disappointed me a bit.

So the fabled tunnel is now proven to exist. But where does it go? It runs down to the basement of the defunct Irish Annie’s Pub at the bottom of the hill. Its original purpose was so that Joseph could travel from his office to his house conveniently, but over the years, it’s very nature of being direct and discrete inspired a few other uses. During prohibition, it was reinvented as a smugglers’ tunnel, which allowed rum runners to transport goods into a speak easy that once operated out of the basement of Irish Annie’s. Astonishingly, the remnants of the actual speak easy can still be seen today below the building, which really hasn’t changed all that much. The basement is a traditional old Vermont cellar, low ceilings, stone walls, and filled with things that crawl. The old iron door into the tunnel is still there too, the very door I was told about so long ago.

Were there other tunnels? Maybe. But the affor-mentioned flood of 1927 and post-reconstruction completely wiped any other leads I could possibly have. And as for that tunnel or cave near the Vector, I wasn’t successfully able to find that either. Perhaps something is still there, just filled in with erosion or a rock slide over the years. Though my lead at The Vector was a bit of a disappointment, I soon found out about other caves in the gorge with their own lore. Some rumored to be the hideouts of smugglers in the embargo act days of the 1800s and dry 1920s, and transitioned as hangouts by local youth and now, cavers looking for a thrill. Some are only accessible by kayak, weather permitting, and offer creepy claustrophobic excursions into dark spaces.

This blog entry has been one of my favorite pieces to write so far. By trying to do research on what I assumed would be a straightforward topic, I kept stumbling on more information and stories that continued to morph and blurred whatever side of the line between reality and fantasy you wanted to be on, far too many for your blogger to fit in this already lengthy article.

One night while sitting in the living room of a former friend’s house, his dad told me their old farmhouse was built in the early 1900s, out of an old barn built in the 1800s, and was dragged to Milton by oxen from its former position where the airport in South Burlington is now. I guess the house contained many other cool details, but sadly we’ve since lost touch.

Another favorite find of mine was a few years back, when a WW2 medal belonging to a Nebraska man was found stuffed in a VCR cassette and stashed inside a tree. No one knew exactly how the medals ended up in Vermont, or why.

Milton is a cool town, and the people who live their have their share of extraordinary stories. I have quite a few other Milton points of interest and esoterica that I plan on writing about in the future. Until then, thanks for the inspiration Milton.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————

If you missed it, I was recently interviewed by Stuck In Vermont and Seven Days. If you’d like to learn a little bit more about your blogger, feel free to check out my interview.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

To all of my amazing fans and supporters, I am truly grateful and humbled by all of the support and donations through out the years that have kept Obscure Vermont up and running.

As you all know I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to produce and sustain this blog. Obscure Vermont is funded entirely on generous donations that you the wonderful viewers and supporters have made. Expenses range from internet fees to host the blog, to investing in research materials, to traveling expenses. Also, donations help keep me current with my photography gear, computer, and computer software so that I can deliver the best quality possible.

If you value, appreciate, and enjoy reading about my adventures please consider making a donation to my new Gofundme account or Paypal. Any donation would not only be greatly appreciated and help keep this blog going, it would also keep me doing what I love. Thank you!

Gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/b5jp97d4