Vermont’s White River valley is full of shoulder-to-shoulder oddities that really communicate the personality of that part of the state. The last free-flowing (undammed) river in the state, its peripherals are loaded with history and mystery incorporated with its beautiful countrified scenery.

Over the years, I heard some conjecture that the Abenaki name for White River pretty much translated as “the useless river”, because of its mercurial behavior; often frozen solid in the winter, a dangerous torrent in the spring, and then shallow in the summer. Neither I, nor the Vermont Historical Society, could find any evidence to corroborate that, but I still find it pretty interesting. Actually, the White River’s name seems to be a bit of a mystery, though it’s reckoned that some settlers who were observing the 60-mile river 200 years ago noticed a white frothiness in its gush near present-day White River Junction, and decided to name it White River.

That etymologic mystique is pretty thematic and kinda sets the stage – the White River is viscous with history and enigma.

There used to be legendary log drives that utilized the river when they could. Nowadays, paddlers and fishermen seem to be the only traffic.

It might have been considerably larger thousands of years ago, which subsequently made up for its untrustworthy nature in the form of natural resources. Vermont Verde Antique – a rare beautiful and coveted form of serpentine is found in the hills between Hancock, Roxbury (the geographic center of Vermont!), and Rochester.

A few of our strange stone chambers – one of my favorite state mysteries – can also be found up in the rocky highlands of a few white river valley towns.

Gold has been found in the river, and ancient Roman coins were once said to be discovered along its banks. Perhaps what’s more puzzling is how they got there…

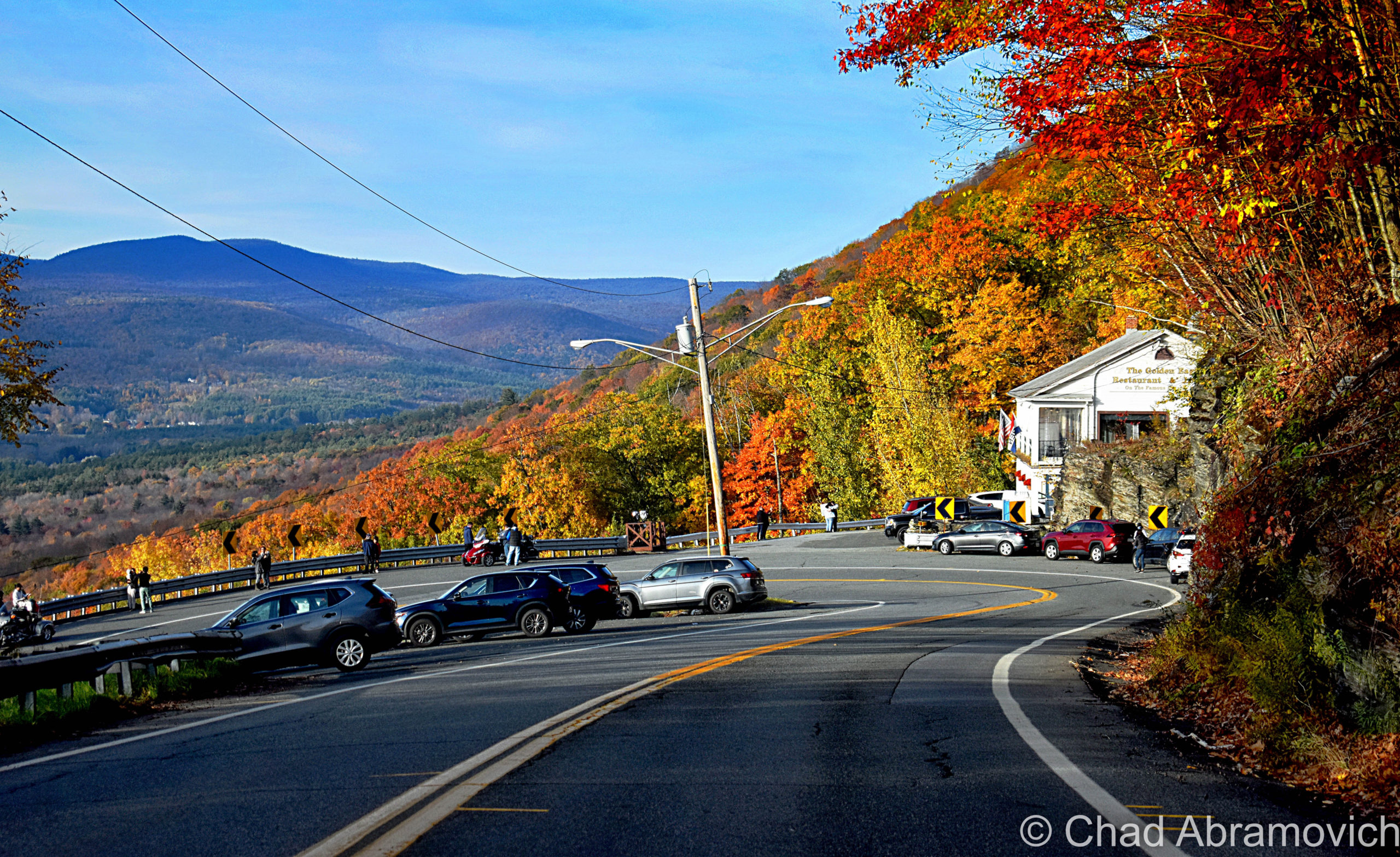

State Route 14 follows much of the White River and zigzags through the neat small towns it carves through like Bethel, Sharon, Royalton, and Hartford, and underneath old rusted railroad bridges that never anticipated a 2 lane road to pass underneath them in their construction. It’s a great drive and would eagerly recommend it to any other Vermont enthusiasts.

If you drive state route 14 along the White River near the tiny village of West Hartford, you’ll eventually spot an unremarkable rusty railroad trestle supported by time-beaten stone pylons and vanitied with a neat fading old Central Vermont Railroad ghost sign. It looks like plenty of other old railroad bridges around New England.

But this one happens to be where the worst railroad disaster in Vermont took place – an affair so horrific that it secured national recognition.

The Hartford Railroad Disaster

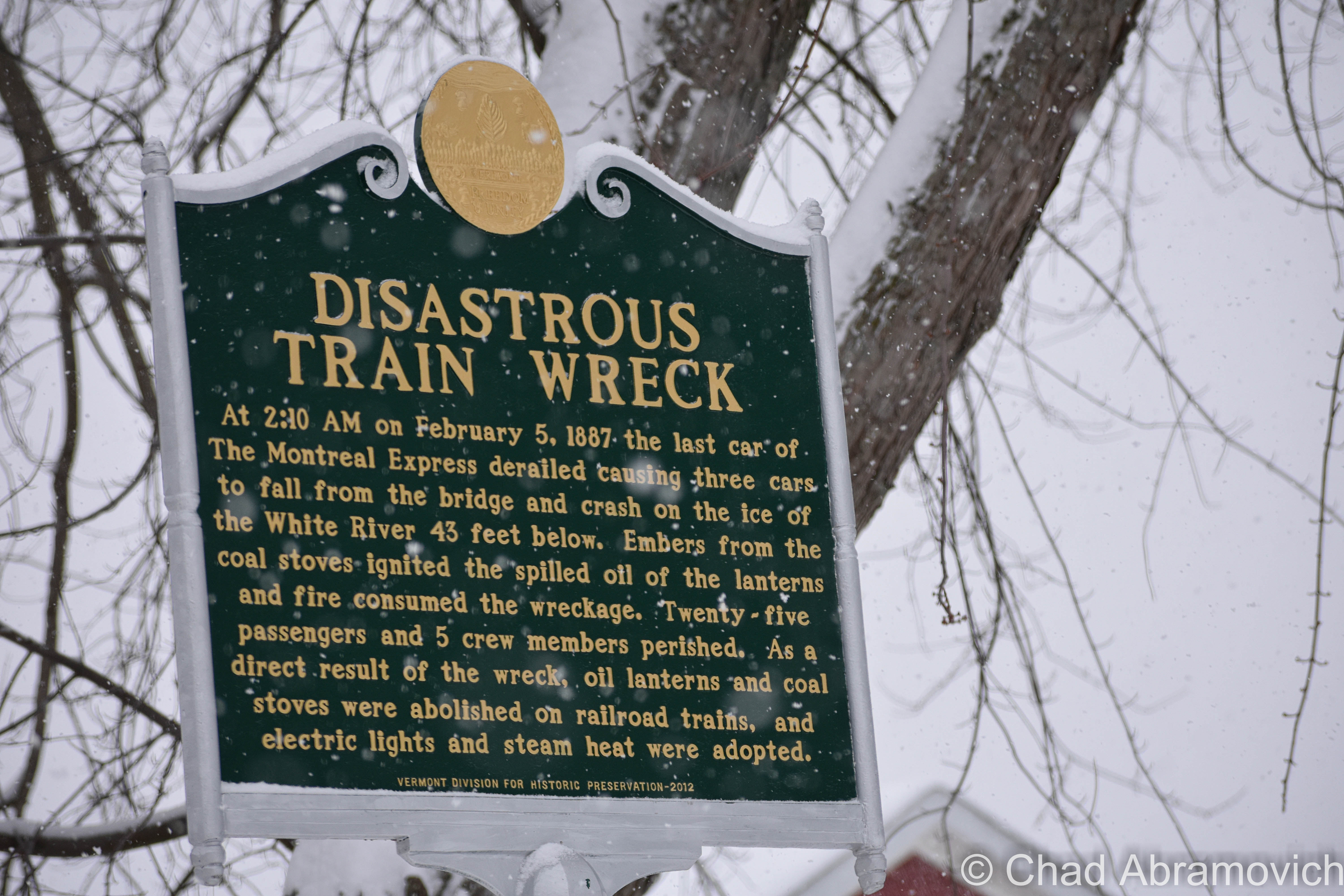

On the early morning of February 5th, 1887, the Montreal Express (also called “The Night Express”) pulled into the depot at White River Junction at quarter past two in the morning, before continuing northward to its titular destination. It was already running about 90 minutes late, so maybe the train was traveling a little faster than usual to make up for lost time.

The night was frigid cold – assaulted by arctic temperatures of 18 degrees below zero. Inside the passenger cars, oil lamps illuminated the interiors while wood stoves tried to fight the vicious chill in the uninsulated coaches.

The locomotive was approaching what was then called “The Woodstock Bridge” (despite not actually being in the town of Woodstock), a high 650-foot-long wooden trestle about four miles west of White River Junction.

Conductor Smith Sturtevant of Saint Albans was making rounds through the train, taking tickets from sleepy passengers and amiably chatting with people he recognized. He was probably also the first person to notice that something was wrong.

As the train was approaching the bridge, Conductor Sturtevant noticed a dull bump and grinding sensation accompanied by a peculiar noise. Instincts took over, and he rushed to pull the emergency bell to signal the venerated engineer Charles Pierce from White River Junction.

Pierce, confused at what the commotion was, curiously peered out both side windows of his cab and saw the back of the train “swaying”, before beginning to slide off the bridge.

Breakman George Parker rushed to apply the brake when he heard the signal from the engine, but by then, it was too late. The whole thing happened so quickly that nobody had time to react.

The engine, mail, and smoking cars made it over the bridge safely, mostly because the coupling that tethered all the cars together snapped and spared them, but the last car in line, a sleeper, hit a broken rail before the span in just the right way, tipped and toppled off the bridge, and dropped 45 feet downwards – pulling three other cars with it – another sleeper and two-day coaches. The cars dangled for a few astonishing seconds, before all falling and smashing against the solid iced surface of the White River.

Brakeman Parker, who noticed that the train was falling off the bridge, made a split-second leap to safety that almost cost him his life while also saving his life. He narrowly missed plunging off the bridge himself and careened down the steep embankment before the overpass touched the river, striking a few trees along the way. He gathered himself, borrowed a team of horses from a nearby farmhouse, and raced four miles back to town to fetch help. “I would have never lived through it had not the snow been deep,” he remarked in an interview afterward.

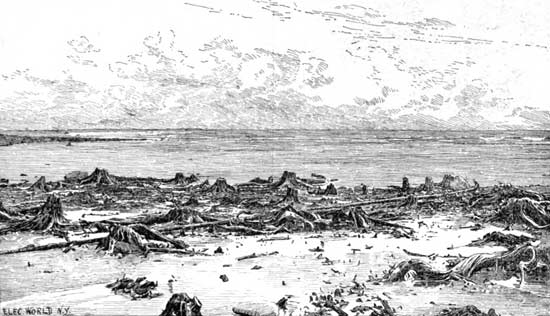

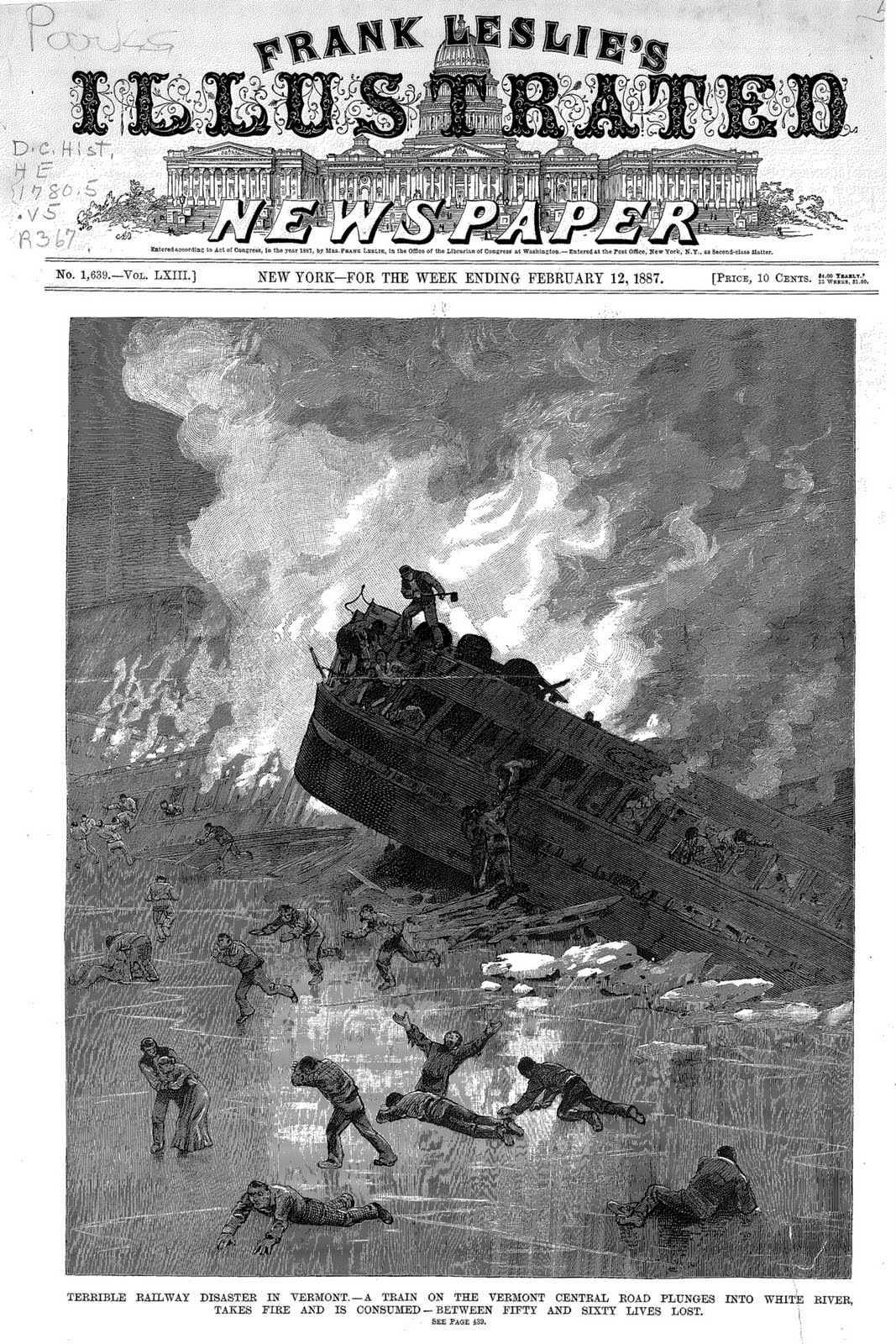

The train cars landed upside down on the ice. The impact ignited the woodstoves and oil lamps, which began to feed off the wooden cars. Wild winter winds fanned the flames into a monstrous inferno, and fiery tongues lapped at the wooden trestle above, until the timbers burned, extricated, and collapsed in a cindery plume below onto the crushed wreck. In less than 30 minutes, the entire bridge apart from its stone supports was gone.

Those confined inside the dismembered locomotive were now introduced to a nightmarish catastrophe.

They were tossed and jostled violently into one another while being pulverized by all the breaking debris as wooden walls, furniture, cast iron woodstoves, luggage, iron rods, and tin roofing all came undone. Passenger Charles M. Hosmer of Lowell, Massachusetts described the encounter this way; “it was all darkness and confusion. I do not remember hearing any screaming, but there were moans and calls for help”

If that didn’t immediately kill them, the conflagration that soon began to spread toward the imprisoned and injured, did. Some were cremated, others were suffocated by smoke or the weight of rubble, and some were mangled to such an extent that although they were able to eventually be extracted, died after their rescue.

Pierce and onboard fireman Frank Thresher of Saint Albans slid down the bank to the broken coaches and attempted to both try and rescue the ambushed and douse the flames with snow. But the blaze was spreading too fast. Pierce then decided to break some windows to try and evacuate survivors, which would wind up helping a few.

One of those people was poor Conductor Sturtevant, who was found by Pierce terribly injured and pinned down by detritus. Through superhuman efforts, they managed to get him out, but not before he was critically burned from head to foot. His ribs were broken and had a fearful wound on the side of his head.

If all that wasn’t bad enough for those who were still caught in the chaos below – the amazing heat from the blaze was starting to melt the ice, creating about 10 inches of water that began to flood the scene and seep its way into the cars. One sleeper car, “The Saint Albans”, had started to sink into the river because the heat had begun to melt the ice beneath a corner where the heavy iron wheels had fractured the surface. If the riders weren’t dead yet, now they had to worry about drowning.

The first batch of rescuers arrived about 45 minutes later with Mr. Parker – the crew including freed and able passengers, town and railroad officials, and reporters, and they all began slogging through the icy water with poles and hooks to retrieve charred corpses and spot survivors, while constantly having to keep back a growing crowd of curious spectators that each wanted to see more than their neighbor. They soon felt exhausted, and their work was far from over.

Passenger Henry W. Tewksbury of Randolph, VT, recalled his experience that was galvanizing to read.

Lawyer, Dartmouth alumnus, and regarded lecturer, he was taking the train home after giving a talk on the battle of Gettysburg in Windsor. He had been sleeping at the time, but was aroused when he felt his car jump the rails. Tewksbury had already been in two railroad accidents before, so he knew what that feeling portended; he realized that another one was going to occur. He jumped from his seat and was about to attempt an exit, but paused as the train deceptively seemed to come to what felt like a standstill. Thinking it was just a false alarm, he sat back down. Then the train leaped into space and crashed.

He was stunned and dazed, not sure if he was dead or alive. As he was trying to shake the gauzy feelings from his head, he tried to move but was alarmed when he realized he couldn’t. That fear was further compounded when he regarded a fire had broken out at the further end of the car. He tried to free himself but couldn’t, so he started shouting – hoping someone would hear him and come to his assistance, but help didn’t come. As he lay trapped and frightened, he noticed an old couple nearby who were pinned down by heavy seats. The pair both seemed to accept that there was no hope for them, so they embraced and fondly kissed each other as the smoke and flames engulfed them.

Falling railroad ties from the bridge above were beginning to crash down around him, and somehow, he escaped being hit. As he was striving to resign to his ghastly fate, he heard voices nearby and started to shout. He was greeted by fireman Thresher and Engineer Pierce. They both came to his aid immediately and had to break his arm and his leg to pull him out. By that point, the flames were so close to his body that all his clothes had burned off.

Mrs. Bryden of Boston (or Montreal, the accounts I’ve read were irresolute) was also in the misfortune. As she was reaching for her window shade, her car suddenly plummeted off the bridge and her surroundings closed in on her. “How I passed those few seconds I don’t know; they seemed eternal” she mused later on record. Her still outstretched hand eventually got the attention of her neighbor Mr. Cushing, and then of rescuers – one of them Mr. Hosmer. She asked for a knife and cut her nightdress off, which was caught and leashing her in place. After she was pulled out, she witnessed the severity of the situation.

“Then I witnessed the most horrible scene of my life. The train could be scarcely recognized. A few men were pulling things out of the car and getting out the people. The train was already on fire. Each car was set on fire by its stove, and the flames leaping up soon set the bridge crackling. The sparks blew mostly to the sky, and the cinders fell on the frozen creek like rain. From the ice I could hear the shouts and the cries piercing the night. One voice still rings in my ears. It was that of a woman. She said “Won’t someone let me out?” The groans of the dying, the fatally injured and those pinioned in the wreck, upon whom the flames leaped devouringly, filled the air” – Mrs. W.B. Bryden

Henry Mott of Alburgh, VT, might have been one of the luckier ones; he was knocked unconscious in the accident and woke up completely bewildered with only minor injuries at the Junction House (where today’s historic Hotel Coolidge is) in White River Junction after being rescued.

Because of the distance rescue teams had to move, by the time they actually arrived at the doomed scene, nothing substantial could be done but eventually just stand back and helplessly watch the horrific exhibition of flames engulfing the beleaguered wreckage and listening to the agonizing screams of those dying. The radiating heat was simply too intense and too dangerous to get near.

The gravest of the wounded were brought to the ironically named Paine house, innocuously named after its owner Oscar Paine, which was both located at the foot of the bridge and happened to be the only dwelling in the vicinity in 1887. As a result, it would briefly become a charnel house. I looked for it on my jaunt down and was sad to see it gone.

The hullabaloo that manifested at the Paine farm was a dismal and pitiful one.

Two back rooms were where the dead and dying were laid out, and the barn was utilized as a makeshift hospital to treat the most brutally hurt. The Paine residence also became the reception place for friends and family who got word of the disaster and made the journey to West Hartford to try and identify their loved ones, or in many awful cases, trying to recognize them just by their mutilated remains. Some arrivers would have to catalog their familiars by what might have felt like pure divination.

The viewing and sorting took about 3 days. Undertakers W.F. Johnson and J.R. Goodrich had the mighty task of trying to piece together individual cadavers as best as they could – which sometimes was simply cleaning them up to their ability, and using twine to sort of fashion them into “shape”, then laying them out to hopefully be claimed before shuffling one corpse out and replacing it with another.

One of the named departed was Frank L. Wesson, second son of D.B. Wesson, of Smith and Wesson Arms manufacturing fame.

Many only had fragments of charred clothing, letters, or personal belongings to work with – like personalized handkerchiefs that were still legible. Doctor H.R. Wilder of Swanton was eventually able to identify his brother Edgar by some of his cards, a suspender with the name “Swanton” on it, and a piece of his skull.

Dartmouth student Edward Dillion was spotted by fellow pupils by his camel’s hair undershirt. He had been otherwise pinned down, crushed, and his head was nearly gone.

One of the most heartbreaking accounts I dug up was the identification of Mr. S.S. Wescott of Burlington – who was found with his young son tightly clasped in his arms.

Though physicians would later attempt to treat and dress his wounds, Conductor Sturtevant would tragically be one of many who wouldn’t survive that night.

A relief train was dispatched, and the probably frazzled Engineer Pierce would drive the rest of the unimpaired passengers dutifully to Saint Albans.

The Aftermath

Obviously, the disaster had many ripple effects and an investigation was launched with fervency by the Vermont Railroad Commissioners.

To this day, no one is exactly sure about the death toll, with the number usually listed as around 37 out of 77 passengers on board, but some accounts run variously higher – Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper announced between “50-60 lives lost”, and others list there were 89 passengers on board, with the death number simply being reported as “many”.

Though Pierce claimed that he had slowed down to 8 miles an hour before approaching the bridge, as was customary to reduce speed before crossing a span, It was doubted and questioned by the inquiry that Pierce actually did so, which cast the Central Vermont Railroad in a debased, negligent light. Their image wasn’t redeemed when it was found that they had used defective iron on the tracks approaching the bridge – some of it was reported to be curved in a cold state and was acknowledged to be unfit for the heavily loaded trains passing over it. Vermont railroad companies of that time were cutthroatly competitive and refused to let competing railroads use each other’s lines, and in order to gain the edge, sometimes corners were cut during construction.

But, the Railroad Commission eventually declared; “The defect in the rail could not have been discovered before it broke,” after they investigated.

Unfortunately, it’s usually horrible circumstances like this that are the ones to goad beneficial change – and the incident at Hartford was so uniquely appalling that Congress and state legislatures knew they had to do something.

While stopping train derailments as a whole was a stretch, they could at least make locomotive travel safer. New safety regulations were employed, replacing gas lights and coal stoves with electric lights and steam heating – things that wouldn’t turn into experience ruining Molotovs. I’m not sure if this was a coincidence or not, but a spell after all this carnage made the papers, the national annual railroad casualty numbers dropped by about 60 percent.

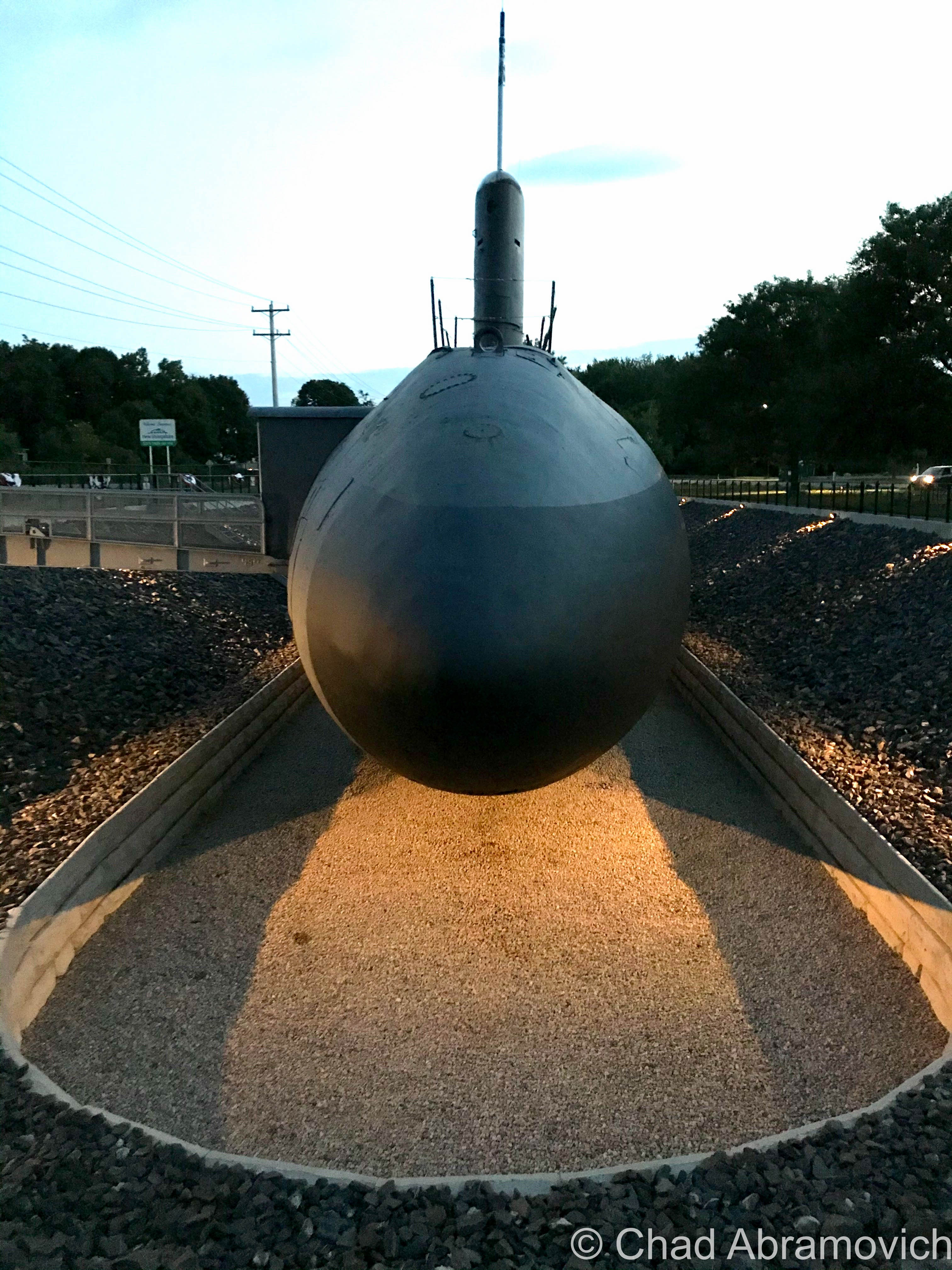

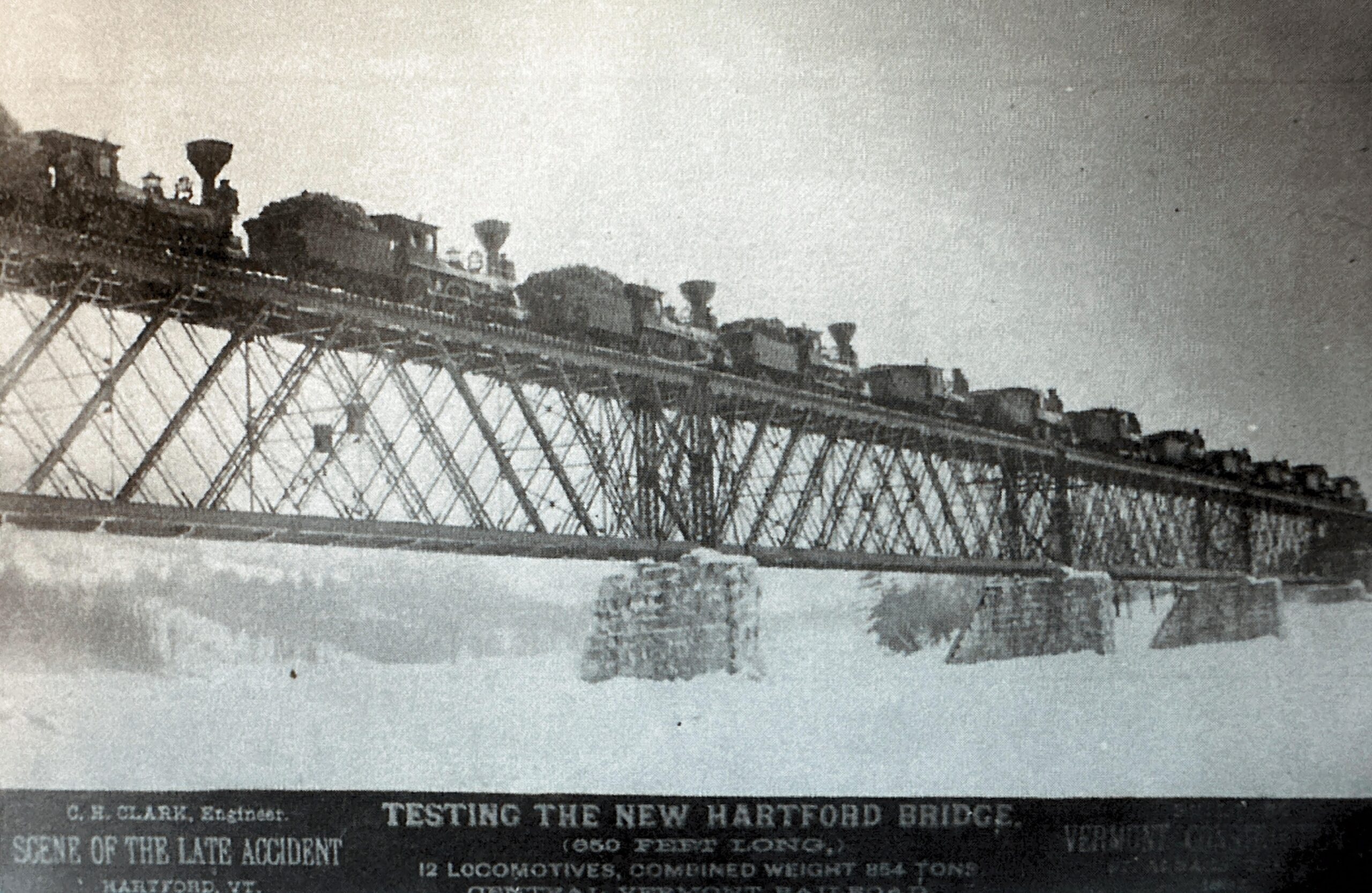

The Central Vermont would rebuild the bridge, and it would double as a needed publicity stunt. The new span would be constructed from fireproof steel, and, they would acquire and park 12 locomotives on it – 845 tons in total, to prove that it could carry the weight.

A Spirited Place?

The pattern seems to be that disasters create ghosts. Dark stories are still said to linger, though I’m not sure how strongly nowadays.

Some residents, or people in the know, have proclaimed to notice the displaced odor of burning wood hanging out near the bridge that has no discernible source.

The shade of a uniformed man has been detected walking the tracks around dusk and into the night. Though it’s hard to say who this corporal entity is, some have speculated that it might be the remains of Conductor Sturtevant. Maybe he’s staying vigil, keeping plaintive watch for future calamities.

It was said that the Paine’s barn was also haunted – stained with the residual sounds of those who died there well over a century ago. Some have admitted to hearing faint cries and hopeless sobbing coming from within the darkened interior at night when the barn was empty. Others have also spotted human-shaped silhouettes standing stone-still within the swarthy barn, as if they were just watching the passersby. The barn, too, is now gone, which I was disappointingly hoping I could have gotten a photo of. Maybe the structure’s eventual extinction somehow gave those trapped cruces a sort of cosmic permission to finally move on, to wherever it is that awaits wayward souls. Or perhaps, they still loiter…

But perhaps the most gripping tale that spawned from the mishap is the ghost of a child. Dressed in old-fashioned clothing, the boy has been spotted around dusk, hovering above the White River as if standing on a sheet of ice that had melted long ago. Whenever these spook tales started to leak into Vermont culture, it’s been said that the ghost is that of a 13-year-old boy named Joe McCabe, who traumatically watched his father burn to death. Though he managed to escape, his battered spirit seems to be ensnared here in the afterlife, lingering over the water, as if he’s waiting for something that will never happen…

Interestingly, I didn’t find a “Joe McCabe” registered in the passenger manifesto. But I did find a Joseph Maigret, A French Canadian boy around the same age who survived to tell his dejecting account.

He and his father Dieudonne were returning to their home in Shawinigan, Quebec after visiting his father’s brother in Holyoke, Massachusetts. Joseph managed to crawl out a window and onto the ice but realized that his father wasn’t following and panicked. He scrambled over and tried to pull him free. But as much as he tried, his dad wouldn’t budge – he just couldn’t pull him out. “Pull me out if you break my legs!” his father pleaded. The hapless boy tried for 10 minutes, but it became too hot.

“He told me to go away. He got out his pocket book and gave it to me, but there wasn’t any money in it. Then he tried to reach around to his other pocket where the money was, but he could not get to it. ‘Tell your mother good by’ he said, and then I had to go away” – Joseph Maigret

Oftentimes in the past, names were sort of “Americanized”, so maybe the French Canadian boy morphed into “Joe McCabe”. If so, is he the ghost? Other children perished in the accident as well, so could the apparition be one whose story has yet to be told?

For some reason, Joe, or Joseph’s tale, was the detail of this story that haunted me over the years. And apparently, I’m not alone in that sentiment. After the disaster, a ballad called “The Montreal Express” was written about it, and a boy credited as “Joe McGrette” was mentioned in the lyrics, which is what I assume is a homophonic mistranslation of his real last name. Below is a video of retired postmaster and Upper Valley local Bob Totz covering the song! (He also has a really neat blog)

And Today?

I’ve been fascinated by this story since I heard it as a kid. The information fluctuated a bit between sources and was a bit of a trial to compare and put together, but it was a captivating project to embark on and brought me a bit closer to better understanding the layers of my home state’s memoirs.

It was a very fitting winter day as me and a friend made our way down to Hartford to get a good look at the old trestle ourselves. We had some fun detouring through off-the-beaten-path towns like Williamstown and Tunbridge, both delightful little villages that look like the 21st century hasn’t completely reached its tendrils yet. I think that’s most of Orange County, though. It’s really a holdout of what Vermont used to be.

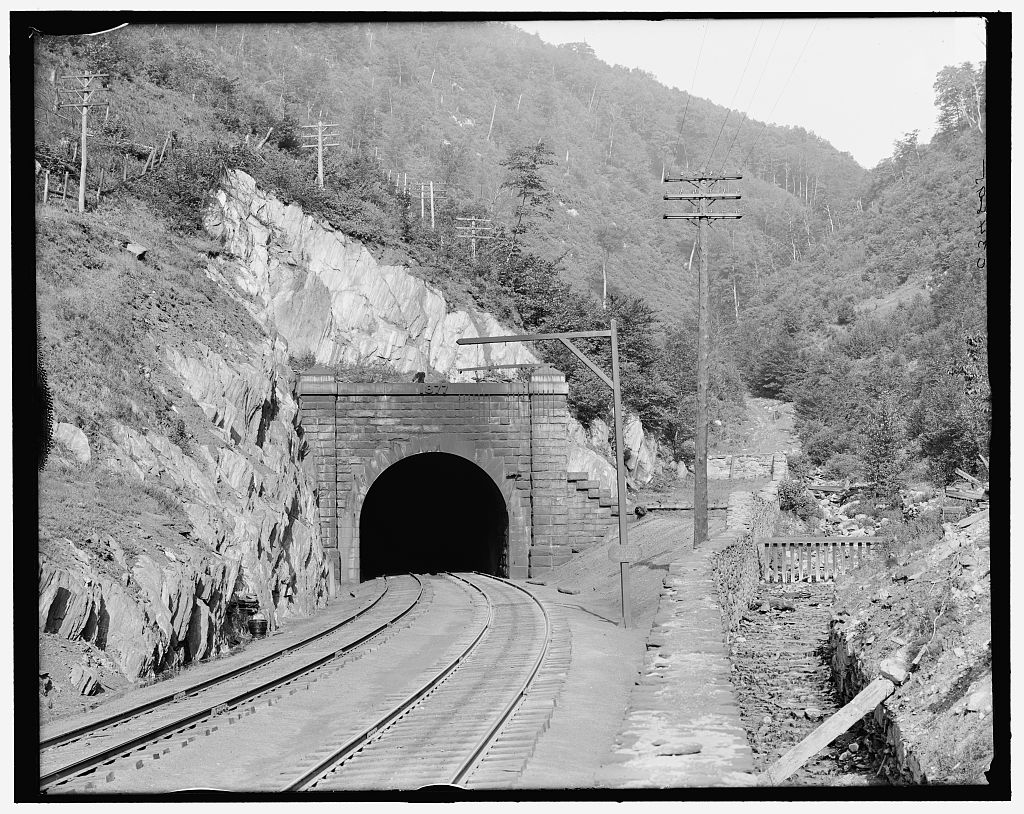

It was kind of surreal to actually see the infamous bridge itself. Or, well, most of it. It’s since been replaced a few times, the current deck plate girder structure was put up in 1935, but the abutments are original, and it still carries train traffic to this day. The last time I was down that way, I caught the Amtrak Vermonter – ranked by Outdoor Magazine as the most adventurous train ride in America – heading northbound.

Admittedly, it was this tragic tale that twisted my arm down this way (and my interest in vintage railroad history), and if I didn’t know about its turbulent yore, this old span would lose its morbid luster and would look like many other common dated ones around New England. But knowing what I did, there was something about the bridge that seemed colder, more sinister, a bit more stained with darkness to my wandering mind. Or maybe it was just my imagination and the howling weather.

Route 14 was lifeless then, and its path slowly became disfigured by rapid snowfall. It was still outside except for that cold snow that whipped at my face in icy sheets, but I wanted to get a good look at the bridge and the river, which felt almost inappropriately serene in the snow. It definitely stoked the thematic mood, my plans to visit during a winter gail were actually just coincidental. It was so windy that I decided that even if anything paranormal did happen, I probably wouldn’t notice it. Are dark stories still told down in the area?

Eventually, I hopped back in the car and headed off to another lamentable local locale, the Maplefieldized Sharon Trading Post for coffee.

Next time you’re down in Hartford on State Route 14, keep your windshields peeled for this oxidized span.

Sources:

An absolutely invaluable source to my research was the booklet “The Great Train Disaster of 1887″ researched and compiled for the Hartford Historical Society by Clyde Berry and Pat Stark.

The Vermont Historical Society has a PDF version of their research on it: “The Wrong Rail in The Wrong Place at the Wrong Time” by J.A. Ferguson which I’ll link here!

Vermont Dead Line, one of my favorite Vermont blogs, has a good post on it here!

“Then Again: The Deadly 1887 crash of the Montreal Express” on VTDigger

It’s also mentioned in William Howard Tucker’s “History of Hartford, Vermont”

Old newspapers like The Boston Herald and The Vermont Standard (Woodstock)

Since 2012, I’ve been seeking out venerable examples of Vermont weirdness, whether that be traveling around the state or taking to my internet connection and digging up forsaken places, oddities, esoterica, and unique natural features. And along the way, I’ve been sharing it with you on my website, Obscure Vermont. This is what keeps my spirit inspired.

I never expected Obscure Vermont to get as much appreciation and fanfare as it’s getting, and I’m truly grateful and humbled. Especially in recent years, where I’ve gained the opportunity to interact with and befriend more oddity lovers and outside-the-box thinkers around Vermont and New England. As Obscure Vermont has grown, I’ve been growing with it, and the developing attention is keeping me earnest and pushing me harder to be more introspective and going further into seeking out the strange.

I spend countless hours researching, writing, and traveling to keep this blog going. Obscure Vermont is funded almost entirely by generous donations. Expenses range from hosting fees to keep the blog live, investing in research materials, travel expenses and the required planning, and updating/maintaining vital tools such as my camera and my computer. I really pride and push myself to try to put out the best of what I’m able to create, and I gauge it by only posting stuff that I personally would want to see on the glow of my computer screen.

I want to continuously diversify how I write and the odd things I write about. Your patronage would greatly help me continue bringing you cool and unusual content and keep me doing what I love!

Do you have any stories you’d like to share? Know of anything weird, wonderful, or abandoned? Email me at chad.abramovich@gmail.com

https://cash.app/$ChadAbramovich